This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

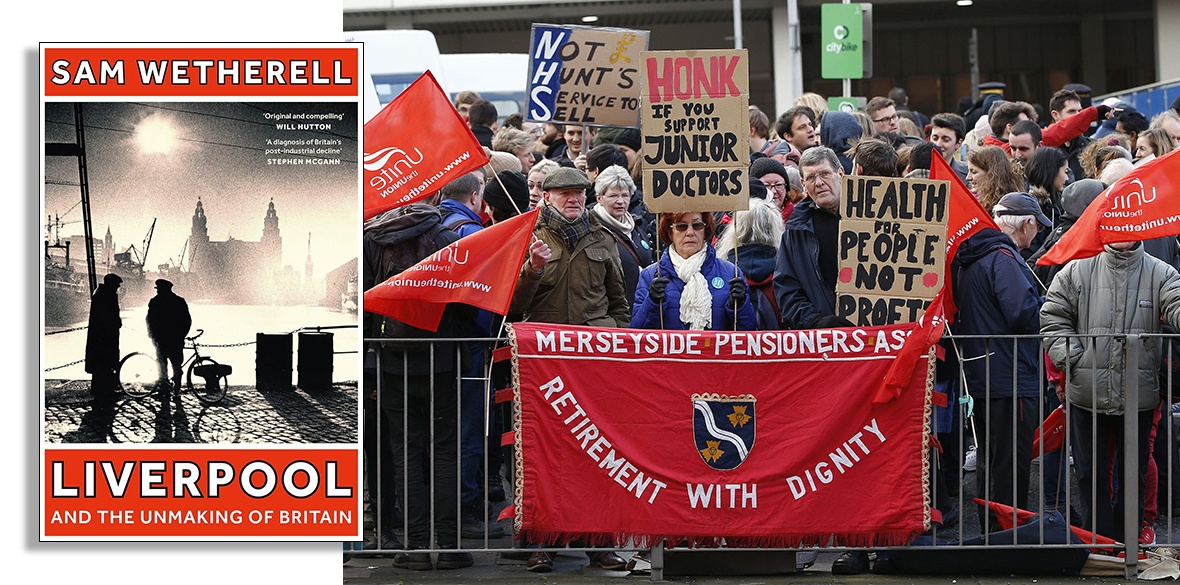

Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain

Sam Wetherell, Head of Zeus, £25

USING Liverpool as a prism to reflect on the “unmaking” of Britain is a departure from most treatments of the city.

Liverpudlians have often represented themselves as apart from the nation, as internationalists and Atlanticists, as more Irish than English.

They have been accused of exceptionalism over the years — as the funniest, proudest, most militant, most sentimental of English urbanites — and often accepted this as a badge of pride.

Sam Wetherell concedes in his opening remarks that Liverpool is something of an outlier — “insurgent, contrarian … patronised, ignored.”

But his choice is more than incidental. For Liverpool was once the model of the future, a trendsetting metropolis with overhead railways, awe-inspiring dockside architecture, booming shipyards and a pioneering multicultural population.

It was the mercantilist port that transformed the north of England from agricultural backwater into industrial powerhouse. It was the Ur-city of the British empire.

The world Liverpool traded with is long gone. The process of its dwindling arguably began with the abolition of slavery acts of 1807 and 1833, but eventually the cotton trade, tobacco, sugar and shipbuilding would disappear too. Between 1950 and 1980, containerisation, combined with failed post-war economic strategies, saw the city’s economy implode and its main social fabric shredded. As Wetherell notes, Liverpool “outlasted the historical forces that conjured it into being.”

While this claim can be applied equally to mill towns, mining villages, foundry towns and other ports, Liverpool fell farthest, fastest and, in some respects, lowest. The urban population almost halved between 1930 and the millennium. Between 1957 and 1983 seven out of every eight dock jobs disappeared.

To this familiar story Wetherell brings an engaging and enlightening interpretation. Focusing on the post-1945 period, he shuns any nostalgia for a putative golden age as well as the oft-told decline story of towerblocks, Blackstuff, Derek Hatton and smack.

His interest is in “obsolescence” in a broad sense that includes the redundancy of much of the city’s built environment and the alienation, marginalisation and in some cases expulsion of its workers and unemployed.

He insists we shouldn’t regard someone’s being “obsolete” as being worthless — as happened most notoriously during the Thatcher era when Geoffrey Howe proposed continuing “managed decline” for Liverpool.

Eleven chapters take us through some of the key events in post-war Liverpool. Wetherell recounts the officially sanctioned abuse of Chinese seamen, black African seafarers and West Indian technicians who were deported, policed or incarcerated after WWII because they were deemed unnecessary and/or undesirable.

He writes about the women who fought to secure safe “play streets” when central Liverpool was redeveloped after 1948. He unearths the rarely told story of Kru workers who fell through the gaps when the docks were rebuilt for container ships and working conditions formalised for white workers.

More familiar to some readers will be the tale of the slum-clearance experiment of Kirkby, where manufacturing projects failed and residents were “scrutinised and pathologised” by journalists and politicians. Surprisingly, I couldn’t find any reference to the Fisher Bendix occupation of 1972, but I did learn about the feminist-led Big Flame, which campaigned for Wages for Housework.

Where traditional subjects — the Beatles, football, Heseltine’s “Disneypool” schemes — are spliced in, they are backdrop and context rather than lead motif. Toxteth and the 1981 uprising are given ample coverage, but with the emphasis on the multiracial solidarity that was exhibited — and airbrushed out of official reports.

In short, we have here a radical history that brings marginalised stories and overlooked people and agencies to the centre. Those looking for solutions might be disappointed but a key argument of this book is that it’s precisely the retelling and reframing that matter most. In this respect it’s a natural companion to Alex Niven’s The North Will Rise Again (2023) which reworked the cultural history of north-east England.

The one serious oversight, arguably, is wider Merseyside and those parts of Lancashire that were tethered to Liverpool in 1974 and are now branded as the “Liverpool City Region.” If anything, obsolescence has affected St Helens even more comprehensively than it has the mother-city.

The unmaking we have witnessed can, Wetherell maintains, “be a source of possibility, even hope.” Liverpool lost its Unesco maritime city status because it needed to grow. It must now shed the tired narrative of imperial golden age and post-industrial ruin to rediscover its worth and redefine its future.