This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

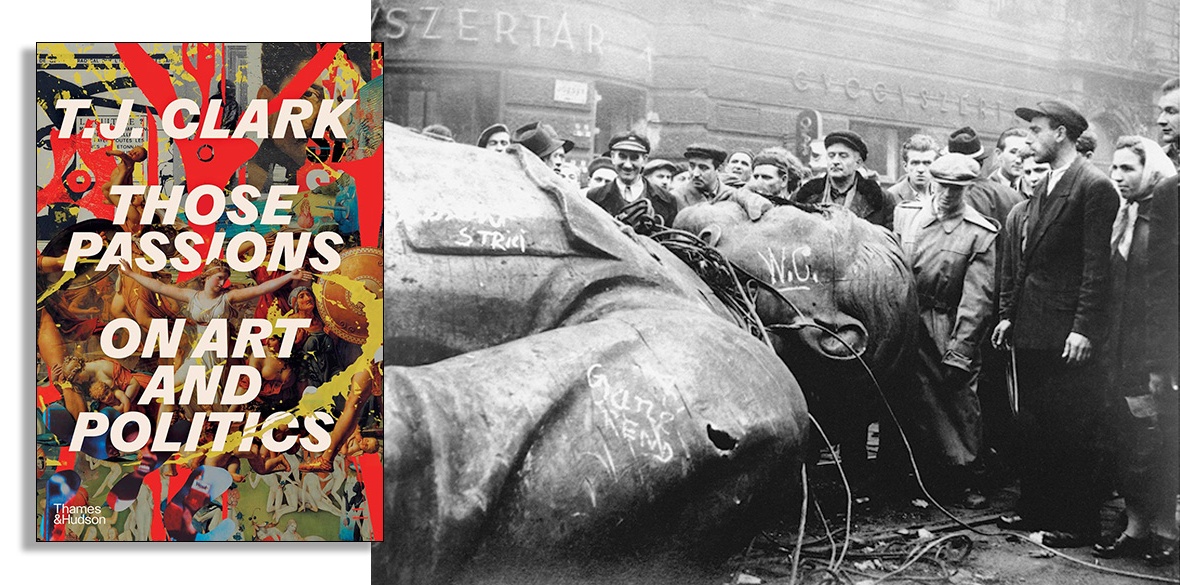

Those Passions: On art and politics

TJ Clark, Thames and Hudson, £40

1848 – the year of European revolutions, the year Marx and Engels wrote The Manifesto of the Communist Party – marked a deep change in the ways in which bourgeois society came to be ruled and in the immediate years that followed, and conditioned by the same processes, realist painting became a thing.

The French state became active as a patron of art in a more overtly ideological and politically significant way than authority and class power had in previous eras. The distinctive feature of this endeavour was, for the French state and, by extension for the French nation, the promotion of a particular understanding of the Revolution.

In TJ Clark’s first two books – The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848-1857 and Image of the People. Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution – a generation of art historians found that – in the collision of art and politics and the interplay of painting and state power – there came a real understanding of the relationship between the profound if barely perceptible movement of the economy and what was happening in people’s heads. And what appeared on the walls of state institutions.

In the introduction to his latest book, a compilation of diverse writings over recent years, Clark reflects on what he sees as the intractability of the problems faced by the left.

He asks: “How can it be, for example, that the kind of opinion of capitalism to be found throughout these pages – the conviction that it remains the one great root of our evils, and that our present politics is paralysed in the face of its power – can be maintained at all, or at least not decline into a mere form of words, without a premonition of its overthrow?”

The theoretical problem at the heart of his writing lies in the sense of loss that the world historic defeat of actually existing socialism engenders even among people who never much took to it when it actually existed.

Where Clark finds little to celebrate in “the eyes of the poor peasants in the 1930 photograph lined up with their rakes and Stalinist catchphrases” he gives voice to the false consciousness of an intellectual class that fails to understand that “the dictatorship of the proletariat is a stubborn struggle — bloody and bloodless, violent and peaceful, military and economic, educational and administrative - against the forces and traditions of the old society.”

The slogan on that banner: “We kolkhozniks are liquidating the kulaks as a class on the basis of complete collectivisation” speaks to the tragic and necessary processes which meant that, with breakneck speed and in response to Stalin’s warning that the Soviet Union had 10 years acquire the material means to defeat an assault from the West, they came with a terrible human cost.

Clark’s aside, that “the shed on the right in the photo might well be a Lager, and the banner read Arbeit, Macht Frie” is unworthy and fits neatly into the poisonous contemporary discourse of historical revisionism which finds no distinction between those who filled Auschwitz and those who liberated it. The relationship between National Socialism and socialism is that of contradiction not continuity.

To be in error on a question of actual history does not, however, negate the main feature of his art historical writing which is, as always, layered, subtle, detailed, set in a sea of context and lightened by the sheer delight he experiences in his work.

The book falls into three parts: Precursors, with his reflections on Bosch, Rembrandt and Velasquez; Moderns, ranging from David and Delacroix through Benjamin, Hegel, Picasso, Pollock and, oddly, Gerhard Richter; and Modernities, where the politics surfaces less unproblematically embedded in aesthetics.

His piece on Art and the 1917 Revolution is the best writing on Aleksandr Deyneka I have read and left me gasping for more on this most interesting realist painter of socialism as it actually existed.

Similarly his commentary on the appallingly mounted Royal Academy show Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932. This bourgeois exercise in manipulation was made bearable only by the realist polarities represented by the paintings of both Brodsky and Deyneka and, spectacularly, the reconstruction of the Malevich Room from the 1932 Soviet exhibition Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic. For a 21st-century audience the representation, by Deyneka and others, of Soviet women in production has evoked very little comment from people for whom the liberation of women is conceived only in forms of language.

But Clark wears his version of Marxism lightly. It is one conditioned by his generation and by an early engagement with situationism and, of course shot through with the intellectual pessimism that lies like a subterranean frost in the thinking of many who came to politics in the years that followed 1968 and who, from all parts of the left, were utterly unprepared, in Europe, for the re-establishment of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.

Some of this despair is evident in his essay For A Left With No Future. Here his insight into “the aftermath of 2008” hints at a notion that in capitalism’s recurring crises there grow the seeds of revolution.

He understands that the prospect of revolution lies in the irreformability of capitalism. But lacking is a sense of agency, for the working class for sure, but also, for liberating power of the global South which, as Losourdo demonstrates elsewhere, is so lacking in the imaginary world of the Western liberal intelligentsia.

Existential despair arises in very particular circumstances. When as impeccably committed a revolutionary intellectual as Walter Benjamin, caught between the advancing Nazis and an impenetrable Spanish border, sees little future in life it moves him to silence his own voice.

From Benjamin comes the question: “Must the Marxist understanding of history necessarily be acquired at the expense of history’s perceptibility?” and it applies with equal force to the history of art.

Clark does a service when he offers Benjamin’s admirably succinct take on the question: “Marx lays bare the causal connection between economy and culture. For us, what matters is the thread of expression. It is not the economic origins of culture that will be represented, but the expression of the economy in its culture.”

Readers of the Morning Star will find much to delight and intrigue them in this astonishing range of subjects.