This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

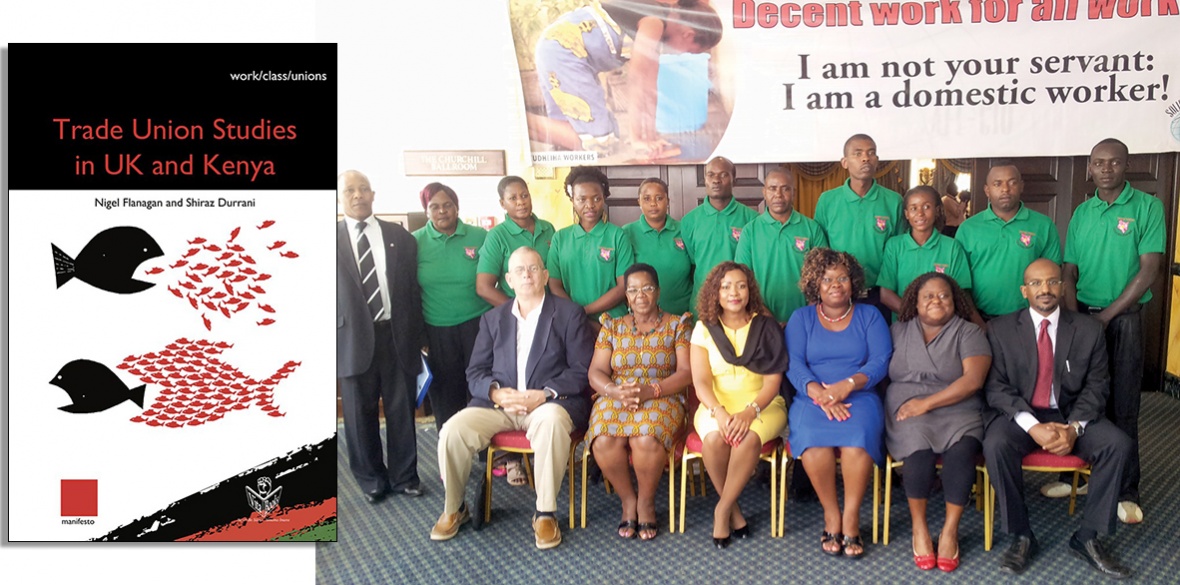

Trade Union Studies in UK and Kenya,

Nigel Flanagan and Shiraz Durrani, Vita/Manifesto, £26.25

SHIRAZ DURRANI has written extensively on the class struggle in Kenya and Nigel Flanagan on organising workers in trade unions. Durrani is Kenyan and Flanagan British and in this book they bring together perspectives and analyses on barriers to trade union organising, and highlight exemplary lessons from the global South and global North.

Flanagan takes an activist perspective and makes a critique of the failures of traditional methods used by union officials. Flanagan’s message is that workers don’t need missionaries and gurus using top-down management-style leadership, with officer-controlled projects and a low level of membership engagement.

“The ideas of solidarity, unity and collective action are more easily understood than the gurus and the bureaucrats believe,” he says. The key is to see members as resources and not as passive actors. He asserts: “No sustained trade union growth has been led by officers.”

Instead existing members have to be the recruiters and he takes examples from Kenya, where a campaign building on every one in 10 members as recruiters resulted in 500,000 new members. The method is called spider-webbing, where volunteer “spiders” get a weblist of 10 names to contact. This is a bottom-up strategy instead of a push-down strategy and the key is communication. “Any action that does not enhance the members is anti-organising,” says Flanagan.

Unions must stop looking to the US and western Europe for solutions, he also suggests. Rather, we must decolonise and drop the narrow thinking: the future lies in Asia, Latin America and Africa. Referring to the Indian million-strong union strikes, Flanagan urges us: “Don’t applaud Indian trade union workers for organising their resistance and then shy away from a UK revival! Follow their example.”

Kenya was a British colony and is today ruled by a capitalist class closely connected to US imperialism. But there was a liberation struggle against the British in which the trade union movement played an important role, influencing the Mau Mau liberation movement. But, says Durrani, ”those who fought in various ways for independence saw a minority elite, groomed under the watchful eye of imperialism, take all the power and benefits of independence.

“Among the losses that working people suffered was the control over their history. Imperialism took charge of interpreting the anti-colonial, anti-imperialist war from their perspective, turning our heroes into villains and our enemies into heroes. Their version of history hid the achievements of people who refused to live on their knees and heaped praise on the Homeguards, the protectors of imperialist interests.”

Trade unions were especially dangerous as they sought alliances and organised on a class basis across ethnic lines, and were therefore more immune to the British strategy of divide and rule. The colonial government suppressed prominent trade unionists like Makhan Singh, Fred Kubai, Pio Gama Pinto and Bildad Kaggia. It also passed on colonial laws that the independent Kenya government continued as there was fear of socialist independent unions.

As Durrani has pointed out: “They thus created imperialist-oriented trade unions that bedevil working class politics to this day. There are valuable lessons to be learnt from the history of the militant trade unions in Kenya and also from understanding how colonialism and imperialism enforced changes that made the trade unions ineffective after independence.”

A central figure that Durrani mentions and has written about, is Makhan Singh. He was class conscious, socialist, anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist, and connected the trade union struggle to liberation of Kenya. Makhan Singh was singled out as one of the gravest threats and was heavily punished by the British with prison for 11 years from 1950 to 1961.

Durrani has been very active in preserving the lessons and history of this struggle: “People need to know their history… but in a class divided society where people do not have the power to keep their history alive, those who do have power manipulate, distort and hide historical facts and interpret history from their class perspective. They thus satisfy their class interests against the interest of working people.”

The debate about organising must not be reduced to one of tactics and training. To meet the economic demands of the working class, it is essential to win political power. And here Nigel Flanagan and Shiraz Durrani are walking in the footsteps of Makhan Singh.