This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

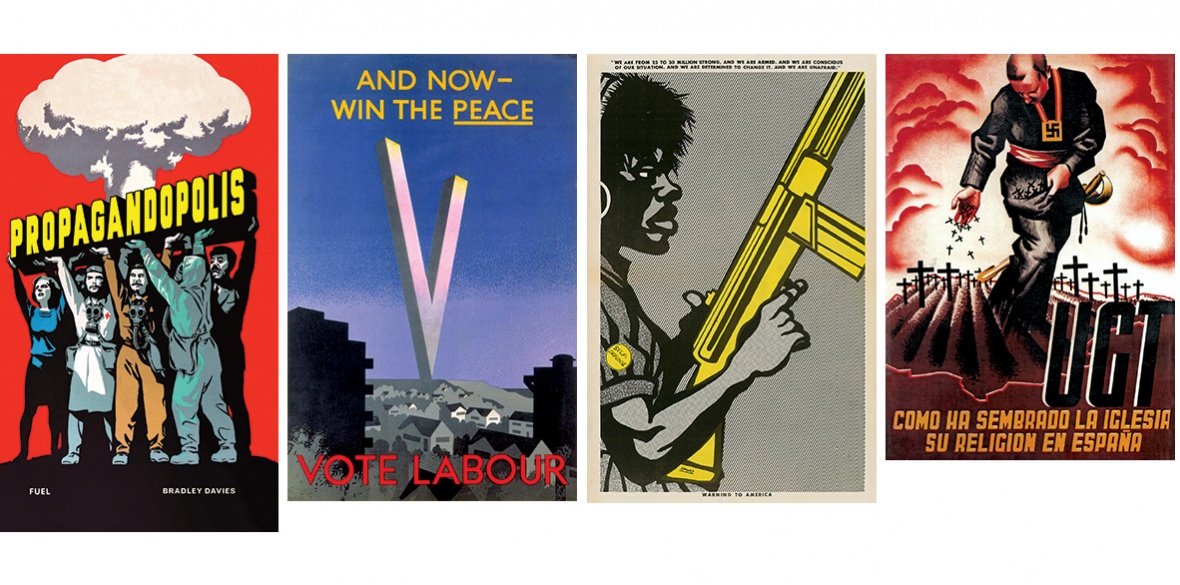

Propagandopolis

Bradley Davis, Fuel, £24.95

WERE you to start a conversation about propaganda you’ll probably never hear the end of it with all parties “propagating” ad nauseam their take on it.

Its etymology is in the Catholic Church’s doctrine Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith) made public in 1622 which was essentially a blueprint for dealing with the Reformation — to put it simply: to delay, at all costs, the political advance of the ideas of nascent capitalism.

During and after the advent of the French revolution in 1789 the term was extended to secular activities. In the English language it acquired a derogatory meaning in the 19th century, while in other languages it retains neutral or positive connotations.

The Vienna-born Edward Bernays — Sigmund Freud’s nephew — was the precursor of modern-day manipulation of public opinion and became a notable guru in US public relations. He employed psychoanalytic techniques and would claim in his Propaganda (1928) that “intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” Debord and Chomsky would disagree.

Bradley Davis’s anthology samples images sourced from Propagandapolis (worthy of a peek at https://propagandopolis.com/) — 62 countries are represented in alphabetical order — from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe.

The focus is on political and social issues. For example the Labour Party’s 1945 election poster And Now Win Peace appropriated Churchill’s “V” sign to good effect, while the 1950 French Communist Party poster Americans To America France Shall Not Be Colonised, financed by Renault workers, attacks the increasing influence of the US in European affairs, depicting it as a menacing octopus.

Elsewhere a comic strip style 1970 Black Panther poster with a militant holding a prominent automatic rifle issues a Warning To America. The sombre Spanish Civil War, 1936-9 UGT (General Union of Workers) poster takes to task the fascism-supporting Catholic Church, and the succinct and brutal 1944 Warsaw uprising poster by the Home Army calls for Every Bullet — One German.

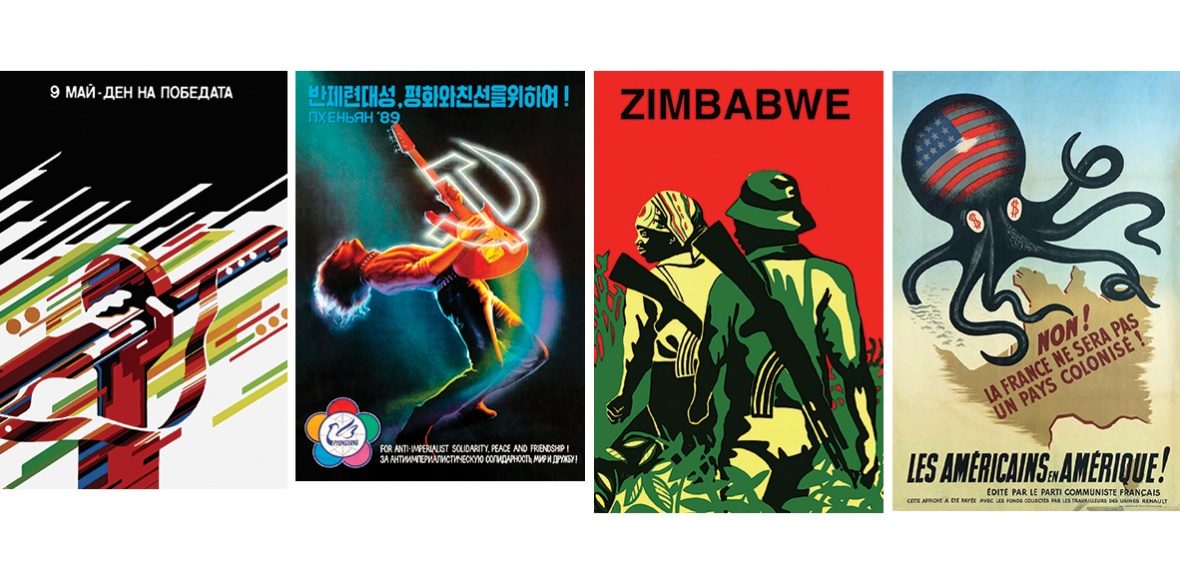

The styles vary from hyperrealist Chinese to concise Soviet posters in the Constructivist tradition, from the innovation of the defenders of the Spanish Republic or the Atelier Populaire of 1968 to the illustrative directness of the national liberation struggles of Angola, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru or Zimbabwe.

The often succinct graphic design catches the eye far more frequently than the actual message that often retains only historical significance.

The Bulgarian 9 May, Victory Day, 1980; Palestinian PFLP Advancing the Revolution 1974; the Soviet No To Racism; or the astonishing North Korean poster for the 13th World Festival of Youth and Students — Festival For Anti-imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship! 1989 all have what it takes graphically.

In a final salvo Bernays (who lived to be 103) claimed that propaganda will never die and, depressingly, he may have had a point.

Davis ends with a rhetorical question as to whether new technology will “herald the propaganda’s obsolescence, or perhaps its absolute distillation and ubiquity?”

Here Western mass media, for once, provide an unambiguous answer. Deluded in its sense of moral superiority it spoon-feeds its populations a siege mentality that purveys fear, instead of enlightenment.

Propagandopolis is availible here.