This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

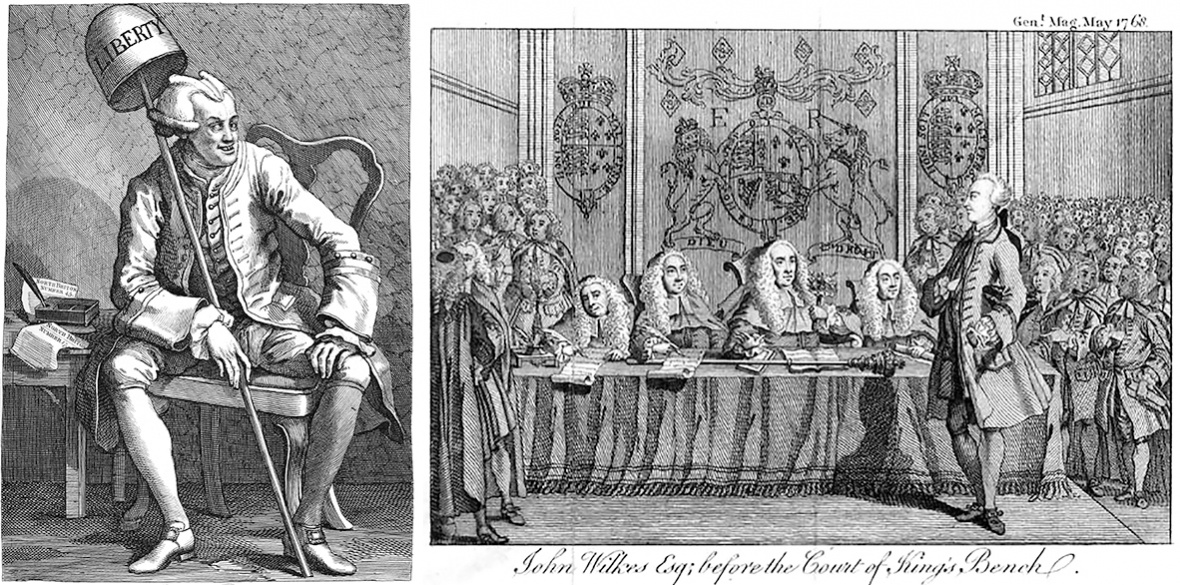

IF you were building a perfect rebel leader from a kit, I don’t think you’d end up with John Wilkes. You’d probably prefer someone who wasn’t a member of the orgiastic Hellfire Club, and who hadn’t been expelled from Parliament for writing a libellously pornographic poem. But there you go: history has its whims.

John Wilkes (1725-97) was and is famous for many reasons, not least his celebrated witticisms, which appear in quotation anthologies to this day. (Any reader who has spent time knocking on doors during elections will appreciate Wilkes’s reply to a constituent who told him he’d rather vote for the devil: “But if your friend decides not to stand?”).

For all the colourful gossip fodder with which his life was filled, however, there was one cause to which he stubbornly clung and which was, then and now, of fundamental democratic importance.

Wilkes insisted that the voters of an area should decide who represented them in Parliament, whether or not their preference matched that of the government. Two centuries later, Tony Benn had to fight the same battle alongside the people of Bristol.

Wilkes considered himself a gentleman, though his origins in Clerkenwell were fairly humble. He was famed equally for his facial ugliness and his powerful charm; he himself boasted that in half an hour he could “talk away his face.” An arranged marriage to an older and wealthier woman allowed him to jump a couple of classes and for a while he lived the life of a country squire in Buckinghamshire and of a libertine in the clubs of London.

He was first elected to Parliament in 1757, but it was as a satirical journalist rather than an orator that he made his name and became a favourite of the working class. Issue 45 of his paper The North Briton published in 1763 accused the government of lying in its King’s Speech. Enemies of Wilkes saw this as an attack on the king himself, and Wilkes was arrested. The magazine was publicly burned by the official hangman.

Government blunders meant Wilkes was soon free, on the grounds of parliamentary privilege. Large demonstrations for “Wilkes and Liberty!” took place widely, and the number 45 became itself a symbol of reform, in Britain and the US colonies, chalked on walls everywhere and even appearing on merchandising such as mugs.

Parliament succeeded in ridding itself of the troublemaker — at least for a while — when a bawdy poem which he had co-authored, An Essay on Woman, was read into the record in the House of Lords by the 4th Earl of Sandwich. This was Wilkes’s naughty past catching up with him: at a meeting of the Hellfire Club, he had terrified Sandwich by playing a trick on him during a seance. The humiliated earl had bided his time, and now took his revenge.

Facing further moves to expel him from the Commons and arrest him, Wilkes fled to France. Convicted in his absence of obscene and seditious libel, on January 19 1764 he was declared an outlaw.

Four years later he was back in London, and determined to be arrested so as to clear up his status as an outlaw. At one point he did manage to get nicked, but a mob of his supporters freed him. He then sneaked himself into prison in disguise. When he was elected as a Radical MP for Middlesex, Parliament expelled him.

He was re-elected at the subsequent by-election, and expelled again. He was re-elected again and expelled again, and re-elected again. By now even the government understood that their tactic of telling the silly voters that they’d voted the wrong way so they’d have to do it again wasn’t working. So they came up with a simpler solution — they declared Wilkes’s defeated opponent the winner.

There is far more to Wilkes’s remaining years than we have room for here; having been elected lord mayor of London, he was eventually allowed to win and keep his old Middlesex seat. The violence of the French revolution seems to have deradicalised him, and in old age, he became a rather conservative figure, content to pursue minor reforms. His popularity consequently evaporated. Nobody loves a centrist.

His concrete achievements were significant, notably forcing the government to tolerate the printing of parliamentary debates for the first time — an essential step towards making Parliament answerable to the people.

Yet the motivation for his extraordinary political life remains unclear. Some believe he was simply a playboy who suffered from chronic boredom and relieved it by making mischief. But if so, he certainly took the joke seriously; he fought duels, was exiled and went to prison several times all in support of radical causes.

You can sign up for Mat Coward’s Rebel Britannia Substack at www.rebelbrit.substack.com for more strange strikes, peculiar protests, bizarre boycotts, unusual uprisings and different demos.