This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE first Labour government was a minority government and lasted just nine months. Was it the product of a cunning Tory-Liberal plot or a wise decision by Labour to prove that it was “fit to govern?”

Against a background of post-war political and economic dislocation, Stanley Baldwin, the Tory prime minister, decided to call a snap election in December 1923.

The crisis facing Britain’s staple industries (coal, cotton and engineering), the impact of the Russian Revolution and a massive strike wave presented major problems for the ruling class and its political representatives (Tories and Liberals) in Parliament.

Both parties were divided — the Tories on the issue of tariff reform and imperial preference, while the Liberals, divided since 1918 and steadily losing electoral ground to Labour, were unwillingly facing their demise as a party of government.

The 1923 election resulted in a hung parliament. Although winning most seats, the Tories did not have an overall majority. Why then didn’t they enter a coalition with the Liberals (158 seats) to keep Labour (191 seats) out? Tariff reform, while a problem for the Tories, was but a fig leaf to cover a more sinister manoeuvre.

In a situation of high and rising unemployment, and without a policy to alleviate it, the Tories were genuinely concerned that it would only be a matter of time before a majority Labour government was elected. Such a government, if its socialist 1918 manifesto was to be taken seriously, would pose a serious threat to the owners of wealth.

HH Asquith, the Liberal Party leader, agreed with Baldwin’s assessment. Clearly, as traditional “free traders,” the Liberals could not in any event support the Tory policy of protectionism — masquerading under the euphemism of tariff reform.

But this was not the only reason that Asquith supported Labour. For the Liberals, a Labour government “with its claws cut” was infinitely better than one which was truly independent. This explains why the Liberals did not, as was in their power, help save the Tory government and instead threw in their lot for nine months to prop up, while it suited them, this first Labour government.

Thus, in January 1924, both parties, although fearful of socialism, saw a minority Labour government, dependent for its existence on Liberal support, as a useful political expedient. The experiment, Asquith declared, could “hardly be tried under safer conditions,” for “it is we who really control the situation.”

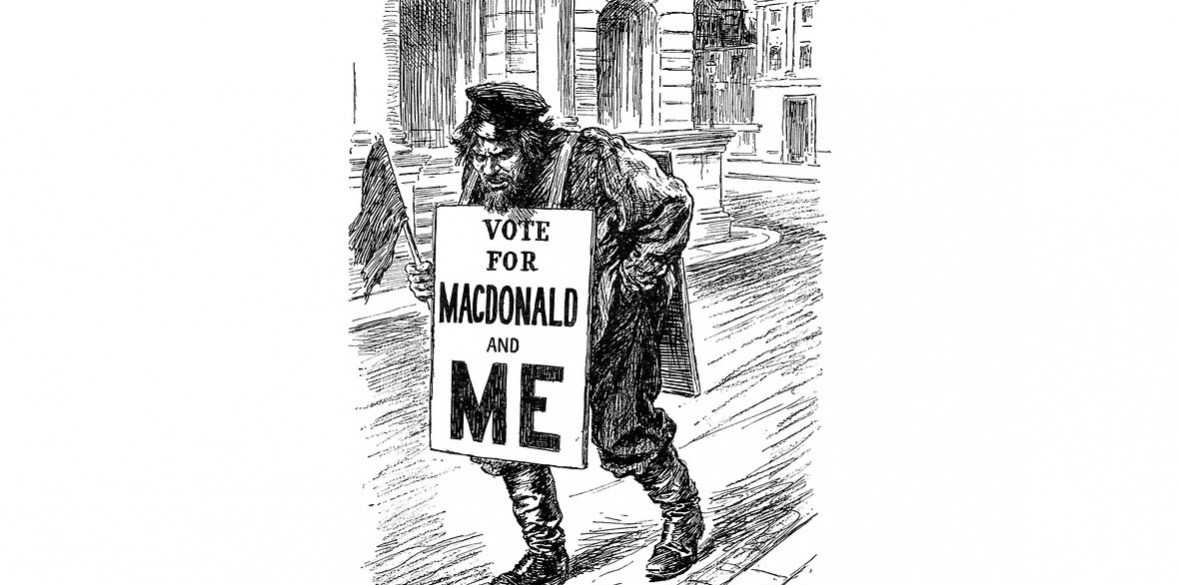

The Establishment parties showed undue alarm at the prospects of Labour’s radicalism, let alone its socialism. Churchill’s gloomy fear that a Labour government would be a “national disaster” was utterly groundless (as was his claim that Ramsay MacDonald was a “futile Kerensky”). Dependent as it was on Liberal votes, this first Labour government was at pains to allay ruling-class fears from the moment of its inception.

MacDonald went outside the ranks of his own party to find Cabinet ministers. He selected Lord Haldane, a former Liberal minister, as Lord President, and the posts of Lord Chancellor and First Lord of the Admiralty went to two Conservatives (Lords Parmoor and Chelmsford, respectively).

Further evidence for the groundlessness of the fears of the Establishment was to be found in the Labour government’s hostile attitude to the rising wave of strikes. The trade unionists in the cabinet — Harry Gosling (TGWU), JH Thomas (NUR) and JR Clynes could be relied upon to support the government anti-strike line. (Margaret Bondfield was the only woman cabinet member).

In fact, the Labour government elevated its hostility to strikes almost to a point of principle. MacDonald, a captive of Treasury orthodoxy, was as concerned as his predecessor, Baldwin, about trade union militancy.

MacDonald followed Baldwin’s policy. The latter had revived and re-modelled the strikebreaking machinery established during the war. This took the form of the innocuously named Supply and Transport Committee (STC).

The Labour government not only retained the STC but strengthened it with the inclusion of notable labour movement figures, including Sidney Webb, Arthur Henderson and JH Thomas.

The STC was utilised in 1924 to combat two major TGWU official strikes: a national dock strike and a strike of London tramway workers. This incurred the enduring wrath of Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the mighty TGWU — Bevin never forgave MacDonald’s perfidy.

Macdonald, in his leader’s speech in London in 1924, proudly declared that he was “no communist” and that “communism, as we know it, has nothing practical in common with us. It is a product of tsarism and war mentality, and as such, we have nothing in common with it.” It is thus surprising that the “red scare” was the issue which toppled the government.

David Lloyd George signed a trade agreement with Russia in 1921 but never recognised the Soviet government. On taking office, the Labour government pursued a similar policy. It entered into talks with Russian officials and eventually recognised the USSR as the de jure government of Russia.

In August 1924, a wide-ranging series of treaties was agreed between Britain and Russia. Official recognition was given to the USSR in exchange for concessions to British holders of tsarist bonds, and furthermore, Britain agreed to recommend a loan to the Soviet government. Again, this was approved by Parliament as a continuation of state policy, and the compensation scheme was especially welcome.

Although the government could have been toppled at any time, the issue which finally settled its demise was not the Soviet treaties; it was the JR Campbell case. Campbell, acting editor of the communist Workers’ Weekly (in later life he would edit the Morning Star’s predecessor the Daily Worker), published the famous “don’t strike” open letter to the army urging them not to act as strikebreakers.

For this, he was charged under the 1797 Incitement to Mutiny Act. On the advice of the director of public prosecutions, Patrick Hastings, the case was dropped even though MacDonald wanted to pursue it. It is thus strangely ironical that this was the issue which brought the government down on a vote of censure.

It is surprising, given the extent of the Labour government’s hostility to strike action and its anti-communism, that the Establishment went to the lengths it did to discredit Labour. This came in the form of the infamous “Zinoviev Letter” — the publication of which was a classic example of Establishment conspiracy and cost Labour, as intended, the 1924 general election.

Three days before the ensuing general election, a letter purporting to come from the Communist International, signed by its president, Zinoviev, was leaked by the Foreign Office to the press and published in the staunch Tory paper, the Daily Mail.

It called for armed insurrection in Britain: “Armed warfare must be preceded by a struggle against the inclinations to compromise which are embedded among the majority of British workmen ... Only then will it be possible to count upon the complete success of an armed insurrection.”

Although the letter was addressed to the Communist Party, the fact that it alluded to the draft treaties on trade and co-operation between Britain and the USSR, which had been negotiated by MacDonald’s government, meant that a connection was supposedly made between the Labour Party and communism.

But this was despite the fact that communists were warned in the letter to “keep close observation over the leaders of the Labour Party, because these may easily be found in the leading strings of the bourgeoisie.”

The fact that the letter was an obvious forgery, and that anyone who was seriously concerned with the truth could not believe for one moment that MacDonald had any sympathies with communism, did nothing to prevent the “red bogey” from distorting reality and doing the sinister job for which it was intended. The Tories obtained a comfortable majority in the October 29 1924 general election.

So, should we conclude, as does today’s Labour Party, that this first Labour government represented a historic moment in establishing Labour’s “fitness to govern?” Conversely, should we see it as a cleverly constructed ruling class trap to which ambitious right-wing Labour leaders, seduced by the trappings of public office, fell prey?

The evidence points to the latter view, compounded by the fact that history repeated itself five years later. The second minority Labour government 1929-31 was also the product of ruling-class machinations.

This time, the consequences for Labour were disastrous. The Labour Party suffered its greatest-ever defeat in the general election of 1931 — losing four-fifths of its seats, reduced to just 52 MPs. Lessons from history are seldom learned.