This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

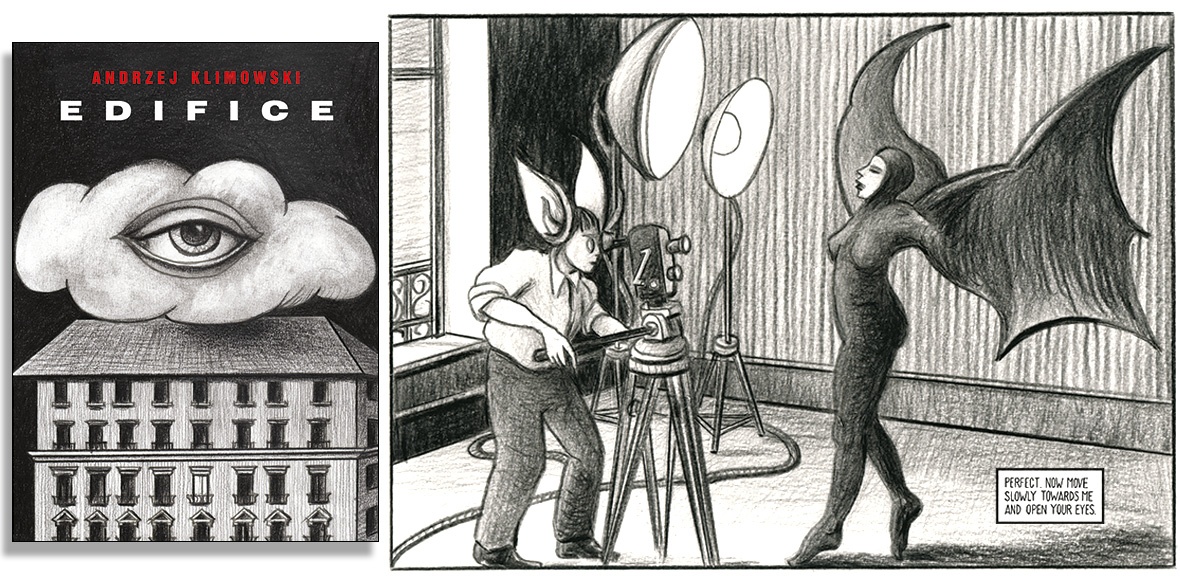

Edifice

By Andrzej Klimowski

SelfMadeHero, Paperback, £16.99

DEMONIC eyes staring from the window of a bookshop in Ealing: this was my first encounter with the work of Andrzej Klimowski. His cover for the Picador edition of Peter Carey’s Bliss was a grotesque and baffling image realised through rotation, shade, juxtaposition and the use of sombre colour. Deceptively simple, disquieting and powerful.

Klimowski – who had already produced striking and enigmatic posters for cinema and theatre – went on to create covers for books by Harold Pinter, Milan Kundura and Dennis Potter. In the 1990s, he branched into graphic storytelling with his dark and dreamlike novels without words (The Secret and The Depository) and his graphic adaptations of stories by Mikhail Bulgakov, Stanislaw Lem and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Later, there was Horace Dorlan, a mixed-modality narrative in which text-only chapters are followed by sequences of wordless graphics. It’s a bravura fantasia involving an academic’s attempts to meld art and science while his sense of reality is under threat.

Klimowski’s new book, Edifice, explores similar territory – the liminal zone between fantasy and rational experience, and the provisional nature of identity and consciousness. It is notable that Professor Dorlan appears in a significant supporting role.

The story opens a few days before Christmas in Engelstadt, a city in which strange transformations and dreamlike manifestations lay siege to the laws of everyday existence. A taxi pulls up in front of an austere apartment block – functional but elegant – and a passenger carries two suitcases to his rooms. What follows may be a real-world ritual or an oneiric imagining: the returning traveller unpacks an ornament – a sphinx – which over several panels becomes a life-sized naked woman. As she clambers from the mantlepiece and dances, the man transforms, first into a stone bust, then into an obelisk.

This sequence sets out Klimowski’s stall in terms of style, storytelling and atmosphere. It takes place over 48 panels – some cover a double page, but most are presented one or two per page. The layout resembles the storyboard for an expressionist movie. Text is used sparingly, for snatches of dialogue and captions establishing dates, times and locations.

While Horace Dorlan paid homage to the classic wordless novels of Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward, Edifice eschews stark, woodcut-style imagery for the fuzzier edges of pencil work.

It’s unusual for graphic storytelling to rely entirely on pencil drawing, and Klimowski’s ability to create light, gloom, atmospheres and ambiguities in that medium is remarkable. There’s a parsimonious elegance to many of the panels; others are crowded with characters, symbols and ambiguous hints about the enigmatic events that unfold. There are fascinating details – shadows subtly out of sync with the characters casting them; flames flickering across several storylines, from candles to fingers and back; and visual hints about the labyrinthine structure of the apartment block.

The narrative is as strange and complex as the building itself. The sphinx-woman transforms into an insect, the obelisk perforates several floors, and the hair of a sidecar passenger is whipped into a vast and lowering cloud. These events intersect with others equally strange: reality is invaded by a young boy’s menacing daydreams, a photographer and his model dress as bats and develop bat-like characteristics, ceilings bleed, hooded figures stalk the corridors, and a sanitorium patient develops a tumour resembling the cloud of hair.

There are indoor crowd scenes – in a cinema, at an aristocratic widow’s soiree, in a hospital TV lounge – but the streets of Engelstadt are as sparsely populated as a cityscape by Giorgio de Chirico. The climax – the soiree led by Professor Dorlan and attended by the avatar of a real-world musician and writer, Peter Blegvad – involves speculation about the meaning of the story the characters inhabit.

Enigmatic, allusive and open to a multiplicity of interpretations, this is visual storytelling with no respect for genres, movements or styles. Read it once and agonise over its meaning. Read it again and spot the allusions to surrealist and symbolist painting; expressionist cinema and film noir; and absurdist and experimental literature. You’ll enjoy the second time just as much.