This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Things are not always what they seem: The Writing and Politics of Malcolm Hulke

Michael Herbert, Self-published, £21.99

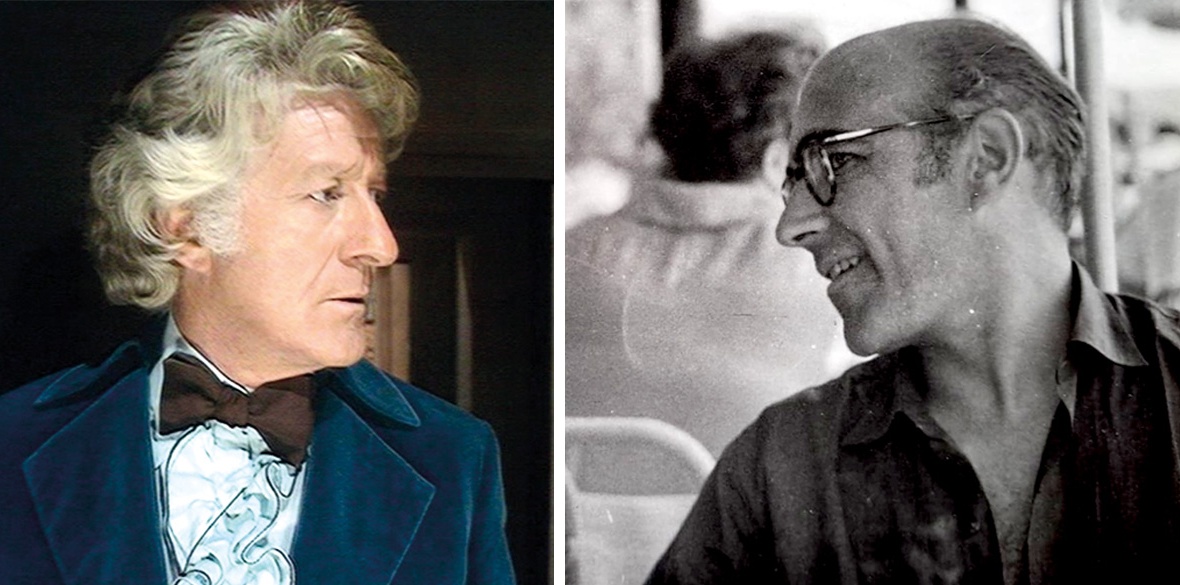

MALCOLM HULKE was an active communist and a highly successful scriptwriter for theatre, television and cinema from the late 1950s into the mid 1970s whose work includes The Avengers, Danger Man and Dr Who.

As he noted in 1975: “During all The Avengers time when the most popular baddies were Soviet spies, my baddies were capitalists. No-one noticed. For seven years running I wrote subversive Doctor Who serials.”

Hulke joined the Communist Party in June 1945, after being released from the Royal Navy, not after reading the works of Marx, but because, as he said: “I had just met a lot of Russian POWs in Norway, and because the Soviet Army had just then rolled back the Germans.” Like everyone who took this step, Special Branch/MI5 maintained a file on him for much of his life, from 1947 to 1963, which runs to hundreds of pages. Files after 1963 have not yet been released.

Michael Herbert’s new biography, which draws on this archive, is a meticulously researched portrait of the man and his times.

An illegitimate child who never knew the identity of his father, he received little formal education, leaving school at 14. His later success as a writer for TV is testament to the value of disciplined self-education in a medium that was still inventing itself.

After the war, he became active in the Communist Party, selling the Daily Worker and electioneering, and was also closely involved with Unity Theatre, serving as its production manager in the mid-1950s.

Hulke also became friends with Ted Willis (later Lord Willis), at the time a leading member of the Young Communist League, and also a talented and prolific scriptwriter.

Willis was also one of the founders, in 1959, of the Television and Screen Writers’ Guild of Great Britain, the trade union for TV, cinema and theatre writers. Hulke became actively involved in the union and in 1960, co-edited the first three issues of the union’s quarterly newsletter Guild News. He also edited the Writers’ Guide, produced by the Guild for aspiring writers, and in 1961 produced a pamphlet to celebrate Unity Theatre’s 25th anniversary.

Unity Theatre was a hotbed of communist and assorted left-wingers keen to develop a proletarian theatre movement, following the examples of Agitprop in the Soviet Union and Brecht’s theatre in Berlin. There, he met writer Eric Paice and the two wrote as a team for television, beginning in the late 1950s with This Day In Fear, which was produced by the BBC, and a further four plays for ABC’s Sunday evening drama series Armchair Theatre.

This remarkable debut portrayed an IRA commander in hiding in London: “When I was a child, I was brought up to believe my people were at war with the English. I joined an army, and I lived by that army’s discipline. I obeyed orders.”

He is found by two IRA hitmen who are disguised as Special Branch officers and have mistaken him for his own assassin. The truth is revealed, and the Republicans make peace.

It is startling that such an overtly pro-IRA drama became a success, and that Hulke and Paice were offered further contracts by both BBC and ITV, given the strict vetting process then in place to keep communists and leftwingers out. But Hulke was writing for television during its “golden age,” and this was London in the era of the blacklisted US producer Hannah Weinstein’s The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955–59) for which she deliberately employed writers and actors blacklisted in the US.

UK television in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, as it evolved into a mass medium, was more open to invention, creativity and experimentation by its writers and programme makers than in the decades that followed, and Hulke’s political views fed into his work, albeit seemingly unnoticed by the powers that be.

In the 1960s, with the Cold War in full swing, he subverted the standard West versus East narrative in his Avengers adventure Concerto, in which Steed teams up with his old KGB adversary Zalenko to protect the Russian pianist Veliko; in his Danger Man episode, Parallel Lines Sometimes Meet, Drake forms a temporary alliance with KGB Major Nicola Tarasova as they seek to discover who has been kidnapping nuclear scientists from both East and West.

But it is the many series he wrote for Doctor Who that made the greatest impact. His Doctor Who scripts were known for avoiding black-and-white characterisation and simplistic plotting. Military figures were presented unfavourably – Invasion of the Dinosaurs and The Ambassadors of Death both have a general as the ultimate villain.

In The War Games (1969), which Hulke co-wrote with Terrance Dicks, himself a self-taught working-class screenwriter whom Hulke chose to mentor, they depict war as violent and pointless, controlled by ruthless leaders who place no value on human life. The Doctor, played by Patrick Troughton, explains: “We’re back in history, Jamie. One of the most terrible times on the planet Earth.”

In his final script for Doctor Who, Invasion of the Dinosaurs (1974), he dealt with the issue of environmental threats. At the end of this serial, the Doctor, now Jon Pertwee, observes: “It’s not the oil and the filth and the poisonous chemicals that are the real causes of the pollution... It’s simply greed.”

In all his work, Hulke’s underlying message to his audience is: question what you think you see or what you are being told by the powerful. Ask yourself what is really going on. As the Doctor says in The Faceless Ones: “Things are not always what they seem.”

The most politically instructive episode in Hulke’s career came when he was commissioned to create a “pageant” for the 1968 TUC conference celebrating its centenary. Hulke’s extraordinary synopsis — quoted in full by Herbert — emphasises the creative tension between the revolutionary and the reformist elements of the movement that culminated in the war effort and the general election of 1945.

“To the Establishment, the war was simply a resumption of hostilities, for King and Country, to maintain the status quo. To the TUC, with its enormously growing membership, it was time to look ahead – really far ahead, and in the heat of battle to formulate and propose long-term reforms when the war was won. It was the TUC which fought for and led the social revolution that was to come,” wrote Hulke.

It was to be like Danny Boyle’s Olympic ceremony but drawn with political clarity. But this telling of history was rejected out of hand by Vic Feather, then assistant general secretary of the TUC, who wanted something “lighter” and settled for songs that culminated in the imperialist anthem Jerusalem. It is likely, suggests Herbert, that this is because he had a deliberate aversion to Communist Party members, whatever their talent. Feather was later exposed as an agent of the Foreign Office tasked with spreading anti-communist propaganda and, unsurprisingly, was rewarded with a life peerage for his efforts.

This episode is a cautionary tale of the deadening effect of right-wing TUC leaderships and their ongoing failure to establish the TUC’s own historical narrative of class-struggle.

Hulke never lost faith in the potential of the mass media for working-class voices, however. He drew on 25 years of writing experience to create the industry “bible,” Writing for Television (A&C Black, 1974), in which he explained the craft and gave practical advice to aspiring writers. He believed that with imagination and hard work, writing could be learned and should be properly paid for, and that there was an onus on those who had been successful to help others onto the first rung of the ladder. He was, for a number of years, the driving force behind the Writers’ School of Great Britain.

He remained a member of the party until at least the early 1960s according to MI5 records, but even afterwards his politics remained firmly on the left, and this was reflected in his anti-authoritarian, environmental, and humanist themes. For this rootless, self-educated man, the party had provided professional contacts, a home, and ideological clarity.

The words spoken by Dr Who are still pertinent in our world today: “You can try to make something better of the world you’ve got. You humans can end the arms race, you can treat people with different coloured skins as equals, you can stop exploiting and cheating each other, and you can start using the Earth’s resources in a rational and sensible way.”

A fitting epitaph.

Things are not always what they seem is available to buy from Lulu.com

The book launch will take place April 9 at 2pm at the Magdala Tavern, 2a South Hill Park, Hampstead. All welcome.