This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

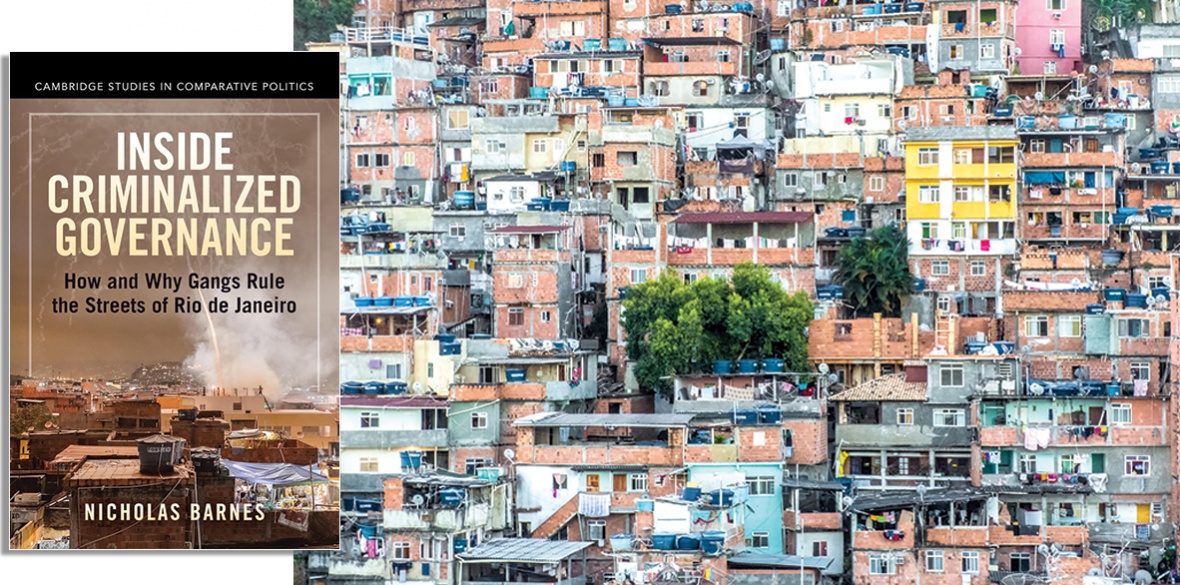

Inside Criminalized Governance: How and Why Gangs Rule the Streets of Rio de Janeiro

Nicholas Barnes, Cambridge University Press £26.99

THE recent extradition by Mexico to the US of 29 drug cartel leaders reminds us of the scale of organised crime in the Americas. Up to 100 million people in the most marginalised communities of Latin America may be subject to the control of criminal gangs.

Crime in all its permutations visits fear, bloodshed and mayhem on vast swathes of the region, particularly its cities, as rival groups compete for territory and illicit spoils.

But gangs can also bring benefits and a modicum of order in otherwise lawless deserts abandoned by the state or where it fears to tread — in short, these criminals can exert a form of governance.

Given the scale of this phenomenon in Latin America, the behaviour of “organised criminal groups” (OCGs) — drug-trafficking cartels, mafias, smuggling networks and protection rackets — has become the subject of growing scholarly attention. And lest we should be inclined to lapse into stereotypes about the lawless character of the Latin population, academics are simultaneously examining gangs from the US to South Africa.

Yet as author Nicholas Barnes points out, despite the prevalence of criminalised governance, OCGs have been mostly ignored as political actors, with social scientists concentrating their attention on states, insurgents, paramilitaries and terrorists. Reasons for this, he notes, include the lack of gangs’ overt political ambitions in terms of capturing state power, allowing academics and observers to sideline them less as mere “criminal” enterprises.

In this, many scholars reflexively assume — according to the Weberian bias — that only states enjoy a monopoly of legitimate violence within their territories, an assumption that is clearly deficient.

Another explanation for this gap in research may be racial bias, with political science blind to the strategies adopted by marginalised sectors: victims of prejudice condemned to live in ghettos, whom Barnes argues undertake counterhegemonic behaviours, such as joining a gang, which are inherently political.

His focus is Brazil, which offers notable examples of criminal governance. The Sao Paulo prison gang, Primeiro Comando da Capital, for example, has established a parallel system of justice over large areas, and Rio de Janeiro’s 1,000 favelas — the subject of this book — are home to numerous gangs that exert a broad spectrum of control in the areas they dominate.

Barnes has studied this spectrum carefully and developed an intriguing set of observations that shed new light on how gangs control their turf and, in particular, how they modulate coercion with the provision of benefits.

This is a masterful study in the essentially materialist motivations of gang behaviour within a certain type of social economy, redolent of Eric Hobsbawm’s fascination with “social bandits.” In his groundbreaking studies Primitive Rebels (1959) and Bandits (1969), Hobsbawm explored social banditry as a crude form of class struggle and resistance.

Barnes argues that the key motivation of gangs is not the pursuit of governance per se, but the threat level. It’s a dangerous world for mobsters and to survive they need the obedience and support of local communities. Gangs therefore use varied patterns of both coercion and the provision of benefits to maintain control against rivals and the police. Coercive practices can include violent punishment for those who break their rules, while the provision of benefits includes dispute resolution and economic stimulation.

It is the degree of threat that determines the form and level of coercion a gang applies, and the most active threat occurs when a competitor seeks to seize territory: this unleashes the dogs of war, and coercion becomes extreme. Barnes writes: “They will remove any existing limits on their coercive behaviour because, in the fog of war, gangs cannot put concern for resident well-being above the need to defend their territory.”

The author develops typologies of gangs and their behaviours that will be of great value to social scientists studying, among other things, the behaviour of rebel groups which, like gangs, often compete over territory and populations.

Barnes writes: “While many rebel groups may obtain the obedience or acquiescence of local populations through the threat of violence, they must also gain the willing or active support of at least a segment of the population if they are said to govern.”