This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

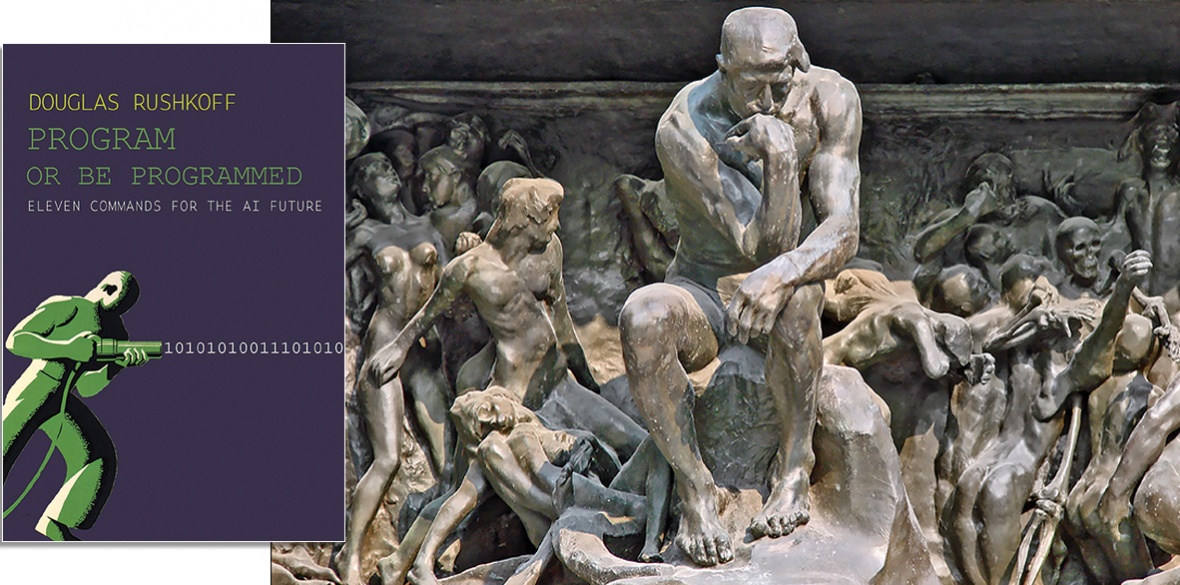

Program or Be Programmed

Douglas Rushkoff, OR Books, £15

THIS critique of the annexation of human planning and decision-making by digital systems was originally published in 2010. The revised edition, which includes a new preface, afterword and reading list, is essential reading.

The arguments at the heart of the book — Douglas Rushkoff’s “11 commands for the AI future” — have gained in relevance over a period in which digital technology has encroached into every aspect of human life and culture.

The book is marred by a fundamental contradiction. Its exploration of the threats and promises of digital tools and systems is haunted by a figure I would characterise as Schrodinger’s CEO. Like the cat in Erwin Schrodinger’s famous thought experiment, Rushkoff’s tech billionaires occupy two contradictory states.

On the one hand, they are figures of declining relevance, passive observers of a technology determining its own future (“we can’t even blame capitalism any more”); on the other, they are “conquistadors” bent on strategic subjugation and cultural colonisation. This unexplored inconsistency is, of course, rendered ludicrous by the recent political manoeuvrings of the owners of X and Facebook.

Irksome, but not a fatal flaw. Rushkoff’s prose is compelling and enjoyable, and his “commands” have the potential to inspire. For example, the chapter entitled Program Or Be Programmed prompted me to enrol on a course in Python coding. As a result, I can confirm the author’s assertion that programming provides a more informed understanding of the limitations and biases of algorithms and digital decision-making.

Chapters are based on core themes but roam into related areas. For example, the segment titled Do Not Be Always On focuses on the impact of screen-based activity on human interaction but outlines further cognitive and behavioural distortions. These include the offloading of decision-making to algorithms, the stress of working at a pace dictated by electronic media and the tendency to value information for its recency rather than relevance.

Other issues tackled by the book include social media’s commodification of friendship, the negative impact of technology on creative industries, the link between anonymous communication and deception, the reductive nature of computer models, the centralising influence of IT and the loss of our sense of place. The final chapter, Value The Human, summarises the anxieties expressed throughout the book.

Writing in 1976, computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum counselled that the greatest danger posed by machine algorithms was not their computational power, but our willingness to attribute intelligence to non-human systems and, as a result, to surrender our judgement to calculation.

The warning went unheeded for decades, but Rushkoff has reframed it in a contemporary context. The technologies described as AI by marketers and tech investors are sophisticated, but in no sense intelligent: they are large language models which crunch through vast datasets on the internet, aggregate the results and produce a string of characters based on statistical probability.

Rushkoff asserts that these are systems devoid of knowledge or thought, in which “there is genuinely no-one home.” They are impressively constructed and could offer the possibility of liberation from monotonous labour but, by accepting their reductive models of the world, we are likely to reduce the possibilities open to us and “keep a particular class of people in power.”

Rushkoff is optimistic about our technological future. He believes that by reasserting the value of personal experience and recognising the aspects of life that cannot be categorised or coded, we can begin to create human-centred systems. Time will tell but, for now, he has given us a clear and accessible insight into the theory, function and psychological impact of our digital tools.