This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

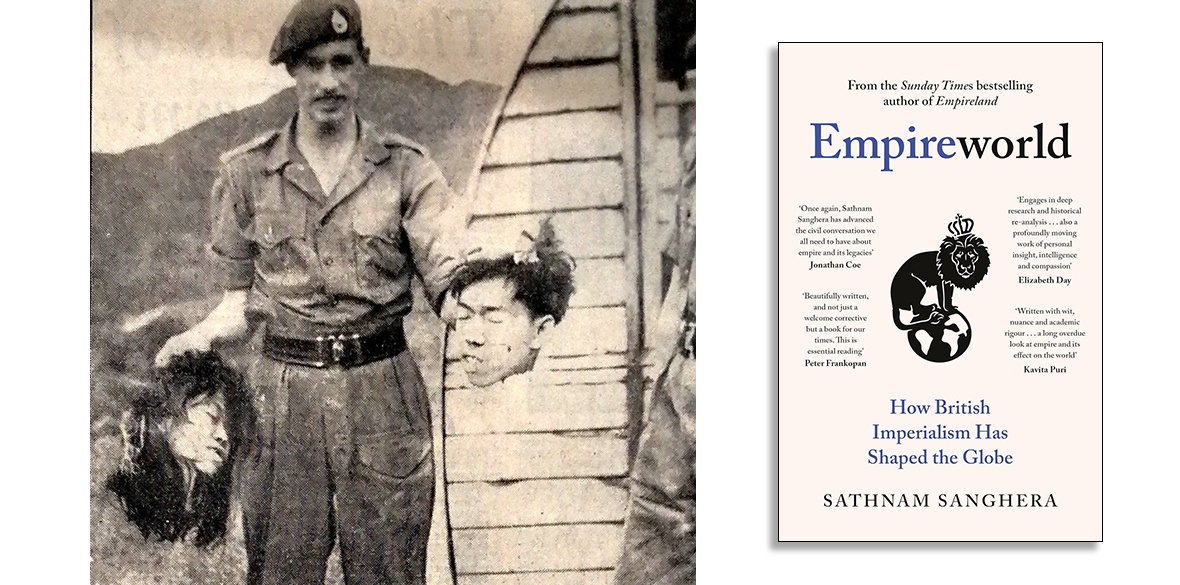

Empireworld

Sathnam Sanghera, Penguin, £10.99

POET and anti-war priest Daniel Berrigan wrote in his book The Nightmare of God: “We would like to think that the empire is virtuous. Or that it can be made so, converted, so to speak, by a large dose of civic virtue.” He concludes that it is not virtuous nor can it be made so.

I agree with Daniel Berrigan — empire is intrinsically without virtue.

In his newest book titled Empireworld: How British Imperialism Has Shaped the Globe, Sathnam Sanghera considers it at best a mixed bag, with the negatives outweighing the positives.

What positives could there be, you wonder. Perhaps literacy or better health systems, clean water or better roads? Any argument that says colonised countries would not have these things if it weren’t for the powers that colonised them ignores the likelihood that these regions of the world could have had all of these and more without colonialism. They could have built them on their own or with the assistance of nations that already had such amenities, without being colonised.

Of course, colonialism is not about helping out the peoples of colonised countries. It’s about extracting the resources of those countries, exploiting their labor and then forcing the product of their labor on the colonised that can afford them. Any potential benefits from the colonial relationship that go to the colonised are usually accidental and never the reason for the colonial power’s presence.

Sanghera reveals as much without ever actually clarifying this phenomenon as his book’s thesis. Instead, he walks the reader through chapters on racism, botany, immigration, legal systems, and much more, detailing various endeavors of the colonial powers (with an emphasis on the British empire) and the effects of those endeavors.

Empireworld is not just another political diatribe against colonialism or imperialism. Instead, it is an examination of where the British put their troops and diplomats, intensified class, ethnic, and religious differences in the countries it had colonised, and the effects (obvious and not so obvious) the empire had on those countries and their people. From the nature of the plant species planted to create monoculture crops for export to the institution of laws against homosexuality, the list of changes to the colonised nations is a long one.

Perhaps one of the more interesting discussions of these changes is the one about the plant species. Sanghera devotes a chapter to this conversation beginning with his description of a visit to London’s Kew Gardens; a description which leads to a discussion of tea, from the growing of it to the marketing of it and the resultant exploitation of people and the environment. It’s a somewhat fascinating tale, to say the least.

Then, there’s the movement of people precipitated by colonialism. From the transportation of humans to the New World to be enslaved, to the immigration of the formerly colonised to the United Kingdom, there were millions of humans whose locations and lives were changed either directly or indirectly because of British colonialism.

In a chapter titled “Phenomenal People Exporters,” the reader is introduced to a wealthy man the author calls Arvin Veerapen. Veerapen’s ancestors included Indians who were transported to the island of Mauritius as indentured servants. Veerapen is now a very wealthy man and part of the class that owns over a third of the island’s land despite their demographic being only 2 per cent of the island’s population. In other words, even though his forefathers were sent as servants to the colony, they are now part of the ruling elite.

An even more drastic example of this is the lesson of the British who left England to “settle” the United States; a process which ultimately wiped out the vast majority of the indigenous people already living on the North American continent. Even though many of the original English settlers were religious dissidents and outcasts in Britain, their first role was to colonise North America.

In a considerably more modern version of those events, one need only look to Palestine, where a maligned demographic in Britain — the Jewish population — was used by its zionist adherents to colonise Palestine. One of the points being made in this discussion is that British colonialism forever changed the distribution of the world’s population. Indeed, it continues to do so.

The essence of Sanghera’s text is to convey that colonialism is insidious, pervasive, positive and negative. Its legacy is inescapable and continues to effect the world.

Nowadays, that belief is strengthened daily by the news from Palestine, the continent of Africa, and even in the stories of racism and anti-immigrant legislation and actions in the mother countries. In other words, the people whose history includes being colonised continue to be mostly negatively affected by that colonisation.

Ron Jacobs is the author of several books, including Daydream Sunset: Sixties Counterculture in the Seventies published by CounterPunch Books. His latest book, titled Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont. He can be reached at: ronj1955@gmail.com