This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

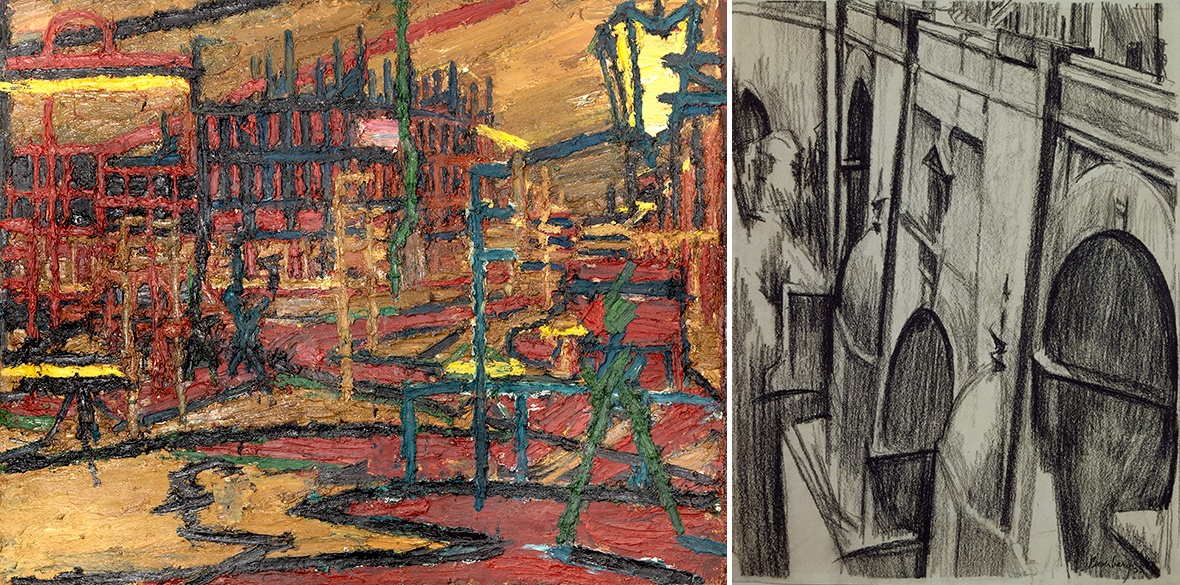

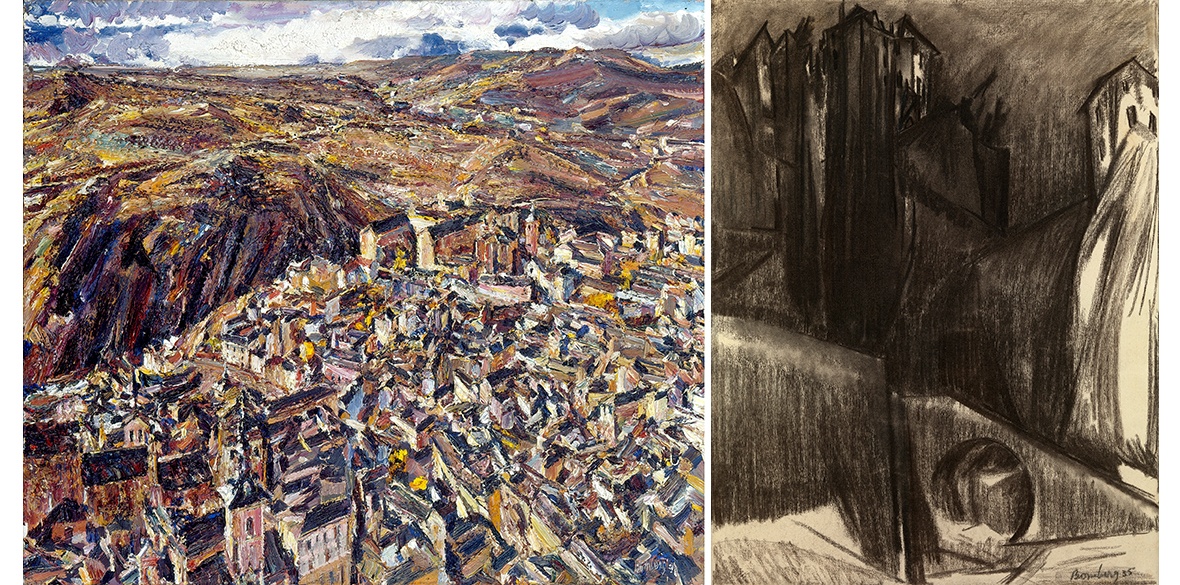

THE sad news that the artist Frank Auerbach died this week invites the occasion to examine the way he, and a few others, dedicated themselves as a revolutionary cell within British art to a remarkable initiative that was lead by David Bomberg, the artist turned part-time teacher, at the Borough Polytechnic in the immediate aftermath of WW2.

Auerbach himself, the orphaned child of German Jews who perished in the Holocaust, was just 17 when he joined Bomberg’s classes. He hadn’t seen his parents since April 1939 and had been raised in the “liberated, puritanical” (as he put it) atmosphere of Bunce Court, a private school that had offered a haven for a limited number of Jewish child refugees. He aspired to be an actor or painter, and was desperately poor.

He had a place at St Martin’s, a “proper” art school, but the course didn’t start until the autumn and the Borough, in the form of Bomberg’s part-time classes offered the chance for life-drawing.

What is surprising is that for the five years he attended St Martin’s he persisted with Bomberg despite the fact that his life-classes offered no formal qualification and, as Catherine Lampart notes in her study of Aurerbach, Speaking and Painting (2015) he “found he was doing one sort of drawing at St Martin’s and another in Bomberg’s classes.”

Bomberg’s classes may have been “exceptionally free,” but their seriousness derived partly from the mix of ages and backgrounds among the students — many were ex-servicemen — and from Bomberg’s own directness. “He came up behind you,” recalled Auerbach, “and said, look at the model, it’s doing this, it’s doing that — I suggest this, and so on. So, it was a practical course of instruction.”

And despite protests that there was no “dogma” to Bomberg’s teaching, one idea was always emphasised, namely that drawing is a way to express the “mass” of the subject. The way it was expressed might be free and change according to the individual student, but the process by which mass can be perceived was the constant. The aim was “to apprehend the weight, the twist, the stance of a human being, anchored by gravity.”

But mass was not something you saw directly. To Bomberg “the eye is a stupid organ” whose perception had to be validated by other senses: by touch and the intuition of three dimensionality. A child, to begin with, is misled by sight, perceiving things to be upside down. It is the experience of “being in the world” and the information of all the other senses that allows for visual data to make sense. These senses had to be reactivated for the new drawing to take place, not to be mislead by the eye, and to allow for the inevitable social and political dimensions of the time and place to be present.

“He spoke of drawing as being simply a question of getting a set of directions for the full 360 degrees around the object. He didnt believe in modelling the thing up artificially to give it weight. Weight was something you felt.”

The panache of a renaissance master, or the slick line of an Augustus John this was not. “As soon as they seemed to be drawing in a way that was mannered or using a cliche learned from art,” recalled Auerbach, “he would refer them back to the model and... suggest a total destruction.” Thereafter, when the student was least aware of having made a drawing Bomberg would say “there is some quality in this form.”

In terms or arriving at a “very exact expression of the object you’re painting, you’re most likely to get it right when you’re least self-conscious, when you’ve given up hope of producing an acceptable image. Because you’re permeated wordlessly by the influence of what you’re painting.”

Bomberg eventually formulated this perception in words that students initially disliked for their whiff of revolutionary Marxism: that art was the attempt to envision “the spirit in the mass.” But Bomberg insisted and the phrase remains the best way of describing the new language of visionary realism that his teaching gave birth to.

And it was new. “I absolutely needed the feeling of breaking through into uncharted territory and working in a world where no rules were known and anything was possible,” stated Auerbach to Robert Hughes (Frank Auerbach, Thames and Hudson, 1990). “I had caught a glimpse of that in Bomberg’s classes: a larger improvisation of gestures that might pull forms out of the air.”

But who was Bomberg, and how had he arrived at this perception of the “mass”?

![David Bomberg, A Self-portrait, 1931 [Copyright Daniel Katz Gallery, London]](https://msd7.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/Bomberg-SelfPortrait31%20%281%29.jpg?itok=k25Qoyes)

David Bomberg (1890-1957) was the seventh of 11 children of Polish-Jewish immigrant leatherworkers who had settled in Whitechapel, London. Despite his impoverished working-class origins his talent — quite exceptionally — had won him a place at Slade School of Art to to study with Walter Sickert.

Auerbach’s dislike of Sickert is instructive: “I resisted his influence because there didnt seem to me to be a sense of weight and mass in his pictures ... [unlike] Bomberg and Rembrandt, [where] the miracle of putting paint onto flat surfaces evoked a sense of mass and space and weight. Sickert seemed flat.” (James Rawlin, Bomberg/Auerbach, Daniel Katz Gallery 2024)

Bomberg’s own rejection of Sickert came in a more confrontational way: he adopted the language of radical futurism and was thrown out of the Slade for subversion. He was then enlisted as a private soldier in the Royal Engineers in WWI and, lucky to survive, fused his futurism with his lived experience in the war commission Sappers At Work (1917).

But the experience of mechanised warfare and mass slaughter had been shattering. He travelled to Palestine and Spain producing vigorous interpretations of landscape. In 1933 he joined the Communist Party and spent six months in the USSR. His Jewishness and his working-class politics, however, kept him out of favour with the anti-semitic and authoritarian establishment in Britain and in 1936 Kenneth Clark pointedly refused to include him in an exhibition exchange with Nazi Germany on the grounds that his art “wasn’t British.”

His exhibitions sold little or no work and WW2 war commissions came with difficulty, and in the postwar period he found himself only able to earn money through the part-time appointment at the Borough. He had no control over who attended the class, but could teach on his own terms and, in response, Bomberg had stopped painting to dedicate himself entirely to teaching as the proper extension of his art and values, even in such unpromising circumstances.

Here, and aware of the shortcomings of the “socialist realist” orthodoxy in the USSR, he developed an alternative, fusing the iconoclastic mission of Modernism — to “make it new” — to the egalitarian mission of communism to define a new, learnable framework for perception. And the mission was urgent: to rebuild from the bottom up an engaged and humanist art after the wholesale destruction of the recent war.

Bomberg’s tough and uncompromising teaching was dedicated to making “the mass” perceptible as both a human and a natural phenomenon that is marked by its time and place, and that carries both visual and political meanings. Both the gravity and the freedom of Auerbach’s painting owes its stability to Bomberg’s single-minded mission.