This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THERE are few more influential writers on history today from a Marxist perspective than Professor John Foster. He has made a major contribution to Marxist historiography and political economy for over 50 years.

Foster has carried forward the work of Britain’s politically engaged Marxist historians, who were writing from the 1930s onwards. Like them, his work is written with a practical purpose, both at home and internationally — whether in the form of accessible historical studies or pamphlets engaging with the issues of today for the labour and progressive movements.

His recent work on Scotland’s economy and promoting progressive federalism is testament to this.

His monographs range from his pioneering Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution (1974) through collaborative studies of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders “work in” (UCS) and other major Scottish industrial events to his latest book, published only a few months ago, Languages of Class Struggle: Communication and Mass Mobilisation in Britain and Ireland 1842-1972.

Through his work, he has notably brought the important work of Soviet historians and linguists on how class consciousness develops and our understanding of revolutionary transitions to a wider audience.

His first book won him fulsome praise from no less than Eric Hobsbawm. But for Foster, his academic and formal teaching career is only one half of his commitment to working-class education and the testing of ideas in struggle.

With endearing modesty, he has supported a generation of students and activists. He did all this while leading a growing department at what is today the University of the West of Scotland.

In his adopted Govan, he has always been “the person to go to” with a problem or issue. From this deeply personal engagement have flowed many successful campaigns over the years. His work in helping to defeat Margaret Thatcher’s Poll Tax is still talked about today.

Against this background, it is only right that politically engaged academics have joined with activists to produce What History Is For.

This is no mere festschrift, as the title makes clear. In honouring Foster’s approach, the essays in all their variety seek to explain the past in ways that inform and can guide today’s struggles.

What History Is For is essential reading for those in the labour and progressive movements who wish to understand the importance of the historical dimension in current debates.

Contributions cover Marxist historiography, the political economy of population health, workplace struggles, class and the national question, community activism and hyper-imperialism.

The collection also includes new work from researchers taking forward Foster’s approach on such topics as religion, Black history and trauma.

Following an integrative introduction by Robert Griffiths, Foster’s long-term collaborator at the Marx Memorial Library, Mary Davis, explores his work as labour historian and Marxist educator, focusing particularly on his influential applications of Marx’s analytical method and theory of history.

Further connecting Foster to the tradition of British Marxist historians, James Crossley argues that religion has an integral place in retelling the story of English and wider British radical history, and in imagining how a transformed world might be brought about.

In two related pieces, Roger Seifert and Jonathan White explore how class struggles develops, and the importance of language, with reference both to historic case studies like UCS and the recent heartening strike wave.

Foster’s former student Chik Collins shows how his analysis of regional policy provides a clear explanation of Scotland’s appalling health crisis — the so-called “Scottish” or “Glasgow effect” — and what is needed to address it.

This, together with Kenny Coyle on the national question, provides a backdrop to Labour peer Pauline Bryan’s assessment of Foster’s influence on Scotland’s Red Paper publications over 50 years. She highlights the pressing need for democratic control of the Scottish economy, progressive federalism and anti-capitalist resistance generally.

Together, Marjorie Mayo and Susan Galloway look at his role as a community activist in the Govan area of Glasgow, setting this in the wider context of community-based class struggles.

Foster was also influential as the Communist Party’s International Secretary, building links with comrades across the world. Appropriately, Vijay Prashad considers the ever-increasing danger of today’s imperialism to the working class internationally and indeed the future of the planet itself.

Finally, David Horsley and Gavin Brewis apply Foster’s interest in communication and oral history. David suggests new avenues of research around anti-racism and anti-colonialism in the largely unrecognised contribution of Britain’s Black communists.

Brewis offers a new and challenging study of the impact of trauma on working class communities through the lens of Glasgow’s “Ned (non-educated delinquent) culture.”

The book’s comprehensive bibliography of Foster’s published work is an invaluable resource for students and activists, and almost justifies the cover price alone.

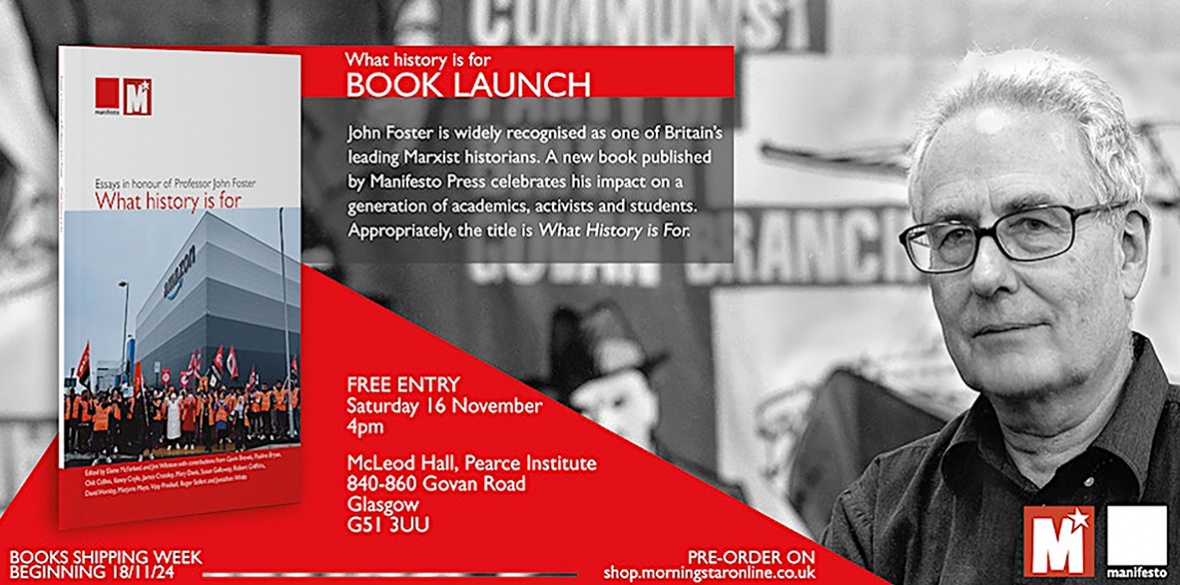

On November 16 in Govan’s splendid Pearce Institute, colleagues, comrades, friends and neighbours will gather to celebrate not only Foster’s legacy, but also his continuing contribution to our movement.

Get your invite to the launch at tinyurl.com/whathistoryisfor.

What History Is For - Essays in honour of Professor John Foster is published by Manifesto Press.