This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN JANUARY this year, researchers reported in Nature Plants that they had managed to remove an object called the Golgi body in the cells of a plant.

This archaically named object is one of the strange complex things that fills the insides of plant cells. It is often described as looking like a stack of pancakes — albeit very small, transparent, and inside all the cells of any plant, or for that matter any animal too.

Advances in genetic engineering techniques mean that scientists can now investigate plant biology by immobilising, cutting out or destroying a given gene and watching what happens to plants that grow without it.

In practice this is often painstaking work. It must be done carefully to create viable plants, which must then be observed closely. However, the resultant advances in our understanding of how plants work have been extraordinary.

In the research reported in January, plants without the Golgi body could live very well. They looked just as green and healthy as plants with their genes all intact. That is, until they were put into the dark.

Plants need sunlight to grow, but most can survive darkness for a while until they start to break down.

The healthy version of these plants generally manage to last about nine days’ darkness before they start to senesce — the leaves going thin and yellow, and starting to shrivel. In the altered plants, this senescence happened in just three days.

Something about the Golgi body was needed to keep them going strong under the stress of living in the dark.

Leaf senescence is not necessarily a bad thing. It is the last step in the developmental growth of leaves, which is a process under careful genetic control.

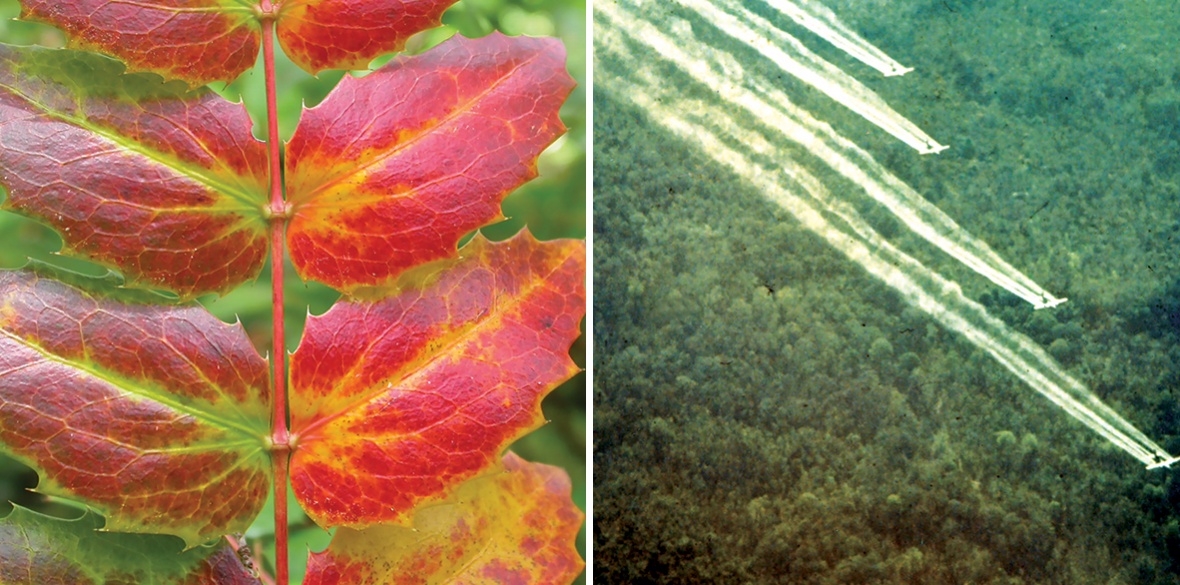

In autumn, the brilliant reds and oranges that transform treescapes are the most vivid exhibition of senescence. During this process, green chlorophyll which is responsible for taking in the light of the sun is broken down into other molecules, in many species bright yellow and red ones.

Biologists argue about the possible reasons for this change. The change may allow nutrients to be reabsorbed into the tree at a time when sunlight becomes scarce. The bright colours may deter insect pests that would otherwise take advantage of the tree’s weakened state.

Some of the ideas about pest-prevention are honest warnings to insects to vacate leaves that will soon fall off, causing the any heedless insect inhabitant to die; or that green insects might be forced out of their camouflaged hiding by the change in environment. What is for certain is that its effects are multiple and complex.

Recent climate change has also given researchers insights into the environmental causes of leaf senescence. Research published last year showed that changes in summer temperature affect the onset of autumn’s colours — hotter temperatures later in the summer push them back.

Human-induced changes to plants and trees don’t stop at climate change. War can radically affect ecosystems. The use of Agent Orange as “herbicidal warfare” by the British in the the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) or the US in Vietnam (1954–75) had catastrophic impacts on human health, causing direct chemical poisoning as well as the destruction of forests and crops.

Deliberate targeting of indispensable food supplies of a civilian population is a war crime.

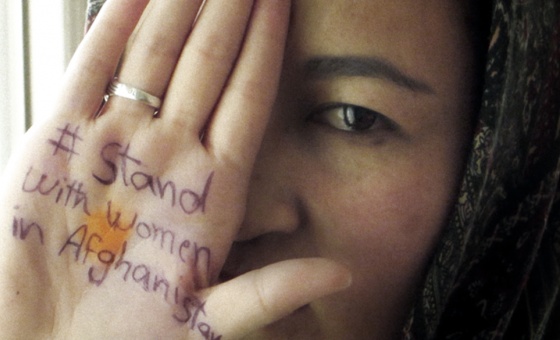

There are of course parallels with the ongoing assault on the people of Gaza by the Israeli military. The attack passed a full year last month, during which more than 43,000 people have now been killed — 2 per cent of the total population — while 90 per cent of people living in Gaza have been displaced.

Israel’s forces have bulldozed crops, bombed fields and uprooted trees, destroying further Gaza’s ability to produce its own food.

Wealth offered no defence. Jawdat Khoudary, a construction magnate and one of Gaza’s wealthiest residents, had cultivated a 100,000-square-foot garden for decades. It was utterly destroyed: “They didn’t leave one plant or one tree.”

A Haaretz editorial said of the recent onslaught on the northern Gaza strip, “If looks like ethnic cleansing, it probably is.”

Israel’s attacks have spread to Lebanon and Iran. Military leaders give no indication that the killing will stop.

Once again, as displaced people in Gaza brace for winter without access to clean water or hospitals, aid agencies fear that lack of food, sanitation and medical aid will be the tipping point for the survival of people in the region.

The last month has seen the fewest aid trucks reaching Gaza since October last year (just 35 recorded by the UN). Worse still, this week the Israeli government passed a law which will stop UNWRA — the agency responsible for delivering the majority of aid to Palestinians — from working in Gaza, with effect in three months’ time.

While Palestinians show persistent strength in dark times, autumn this year brings little promise of freedom or promise of getting old.

Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote in exile and died in 2008. In his poem I love autumn and the shade of meanings, translated by Mohammad Shaheen, he wrote: “I delight in the truce between armies / awaiting the contest between two poets / who love the season of autumn, yet differ / over the direction of its metaphors.”