This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

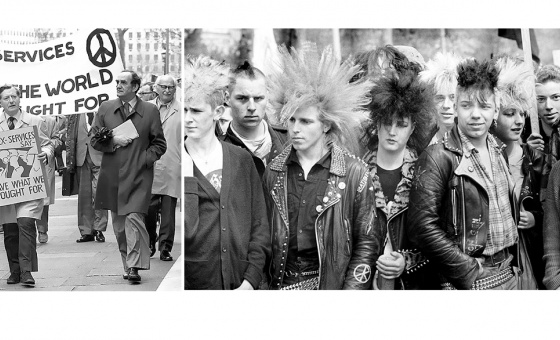

AT THE start of the year, trade unionists marched through Cheltenham in defiance of the Conservatives’ attack on the right to strike.

The Cotswold town was picked to commemorate another battle to defend trade union rights 40 years earlier, when Thatcher banned trade unions at intelligence hub GCHQ, headquartered there.

Now Civil Service union PCS has unveiled a 40th anniversary exhibition to mark the start of that historic struggle. If you have a spare hour in London over the next month, pop into the union’s Clapham HQ and take a look — it’s open to the public.

“It’s important that we remember [the fight for the right to be in a union at GCHQ] because it was a victory,” former PCS deputy general secretary Hugh Lanning, a key figure from the long campaign, pointed out at the exhibition’s launch on Thursday night.

Many of the industrial struggles whose anniversaries we mark were defeats — and 1984, the year the ban on unions at GCHQ was announced, is more famously the year the great miners’ strike began.

Events to commemorate the miners’ strike are often inspiring — the heroism, collectivism and community spirit speak to the fundamental values of trade unionists — but Thatcher’s victory, with all its awful consequences for those communities and the labour movement more widely, hangs over them.

Here the mood is more upbeat. It took 13 long years, and the election of a Labour government, to end the ban on GCHQ employees joining a union.

But the ban was overturned: and more than one speaker at the launch drew parallels with the way today a newly elected Labour government is overturning the anti-strike laws imposed by Tory administrations from 2010-24.

“For 13 years, we campaigned for the right of ordinary people to belong to a trade union again,” Lanning said. “And not only did that right come back to every member of GCHQ… they got the offer of jobs, they got their pensions.

“The union was recognised… we were welcomed back to negotiate the return of trade unions, and since then the GCHQ branch has become one of the biggest and fastest-growing branches in the union.”

Lanning pointed to the importance of maintaining constant pressure on Labour in opposition to the eventual victory, citing the late Mike Grindley, a sacked GCHQ worker who was a core leader in the campaign, collecting no fewer than 41 promises from Labour that it would restore trade union rights if elected.

“Every time he met them he would go: ‘You’ve promised 38 times, do you still promise…’”

The constant repetition of the demand hammered home the commitment and ensured by 1997 Labour had no option but to keep to it, he pointed out.

Even in the 13 years of continued Tory rule, the campaign’s regular public demonstrations and protests had their effect.

Lanning noted that GCHQ was a test case: had Thatcher succeeded in winning broad acceptance of the removal of trade union rights from the intelligence agency, this would have been rolled out in other departments linked to “national security,” such as the Ministry of Defence. But the fact the GCHQ ban remained a live controversy for 13 long years prevented this.

He saluted the steadfastness of the sacked trade unionists of GCHQ, who were given a deadline to cancel their membership or be sacked, and took the hit.

“You need to remember the decision they faced — if you remain a member of a trade union, you’re going to lose your job, your career, your pension. That’s not a decision that individuals can take by themselves: it’s a decision they need to take with their families, and stick together, and they all did for all that period until unions were restored.”

PCS general secretary Fran Heathcote says the lessons of the GCHQ campaign are relevant to how unions can fight and win today.

“It was a win, and it took 13 years. It was a long-running dispute, and listening to the speeches tonight, you hear about the determination and resilience and how people kept their spirits up during what was an incredibly long campaign.”

For Heathcote, in a sense unions are now embarked on reversing an even longer-running war on union rights, that waged by every government since Thatcher’s.

Secondary action took place during the GCHQ dispute, with other workers walking out in solidarity.

Lanning had mentioned ringing round branch secretaries in other parts of the Civil Service and succeeding in getting their workforces out — not something possible under today’s anti-trade union laws.

“We’ve just got a new government which has introduced its employment rights Bill,” she says.

“It doesn’t go far enough in key areas, but we have to recognise this is more than has been achieved in 40-odd years in terms of restoring trade union rights.”

The New Deal for Workers, like reversing the GCHQ ban, was something delivered by Labour only as a result of serious sustained pressure on the party from the trade union movement.

Unions are already in discussion about how to put pressure on Labour to “deliver more and deliver better,” she says. “The employment rights Bill doesn’t come in for two years. So what happens in the meantime? What’s the direction of travel for government?

“It would be naive to think that with the new government all the issues go away because they clearly don’t. We anticipate big campaigns and potentially disputes over pay and jobs and job security.”

Noting that Rachel Reeves has said Labour will be a party of investment, she adds: “Let’s see her invest in her own workforce, give our members and public-sector workers a decent pay increase.

“The things we’ve lost over the last 40 years in terms of employment rights are things we want back and we’re not going to wait another 40 years!”

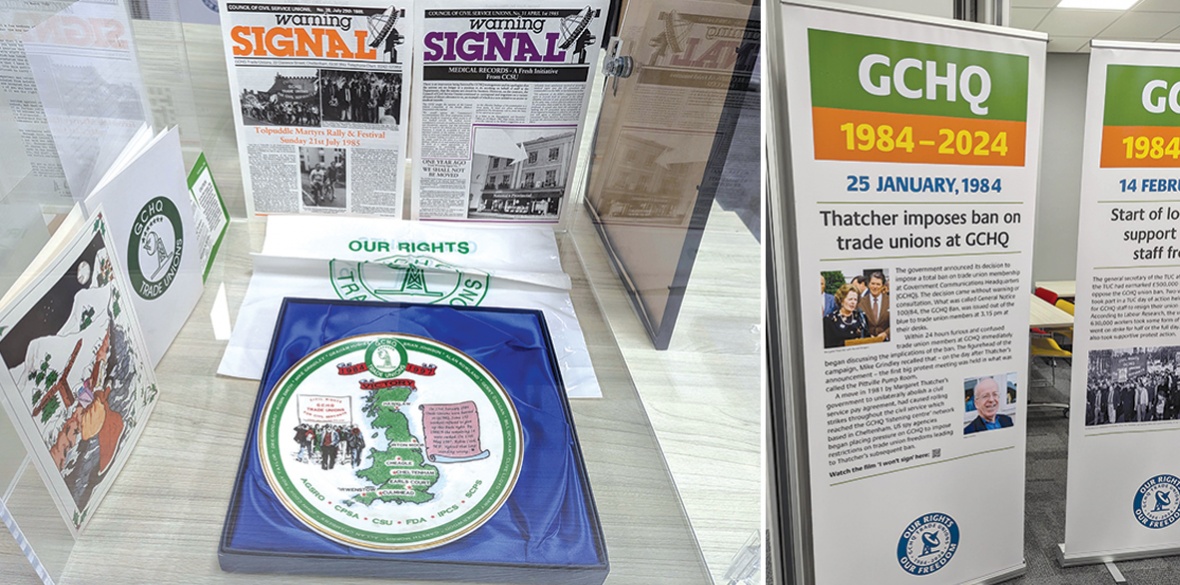

The exhibition fills a room of the union’s HQ, pop-up stands telling the story of from the initial ban through the years of campaigning, and ending with this year’s demo and the delivery of an employment rights Bill this autumn.

Cases hold mementos of the strike, with badges, banners and copies of the campaign magazine Warning Signal, as well as a GCHQ unions banner. I learnt from it — not having realised, for instance, that the original ban was another case of Britain fawning on the United States, with Washington putting pressure on Thatcher after Civil Service strikes had spread to the intelligence agency, affecting the US’s receipt of information from its “listening centre.”

Mike Grindley’s two sons were at the launch, together with campaign veterans and surviving sacked workers. On learning who I am, Neil Grindley laughs: “That was my first job, picking the Morning Star up off the doormat and putting it on the kitchen table so dad didn’t have to bend down!”

It was a reminder that, with determined campaigning and consistent political pressure, our movement can and does win.

Drop in if you’re in the area — this is a chapter of our history that should not be forgotten.

The exhibition is open from 9am-4pm on weekdays until November 15 at PCS headquarters, 160 Falcon Road, London SW11 2LN: ask at reception.