This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

SIPHOKAZI MAGADLA is crystal clear about the relevance of her historical work to contemporary South Africa and the wider world:

“The erasure of women’s contributions to the history of the anti-apartheid struggle is connected to the dismissal of women’s roles in the new democratic state. If women didn’t matter in how we got to be liberated, then why would their roles matter now?”

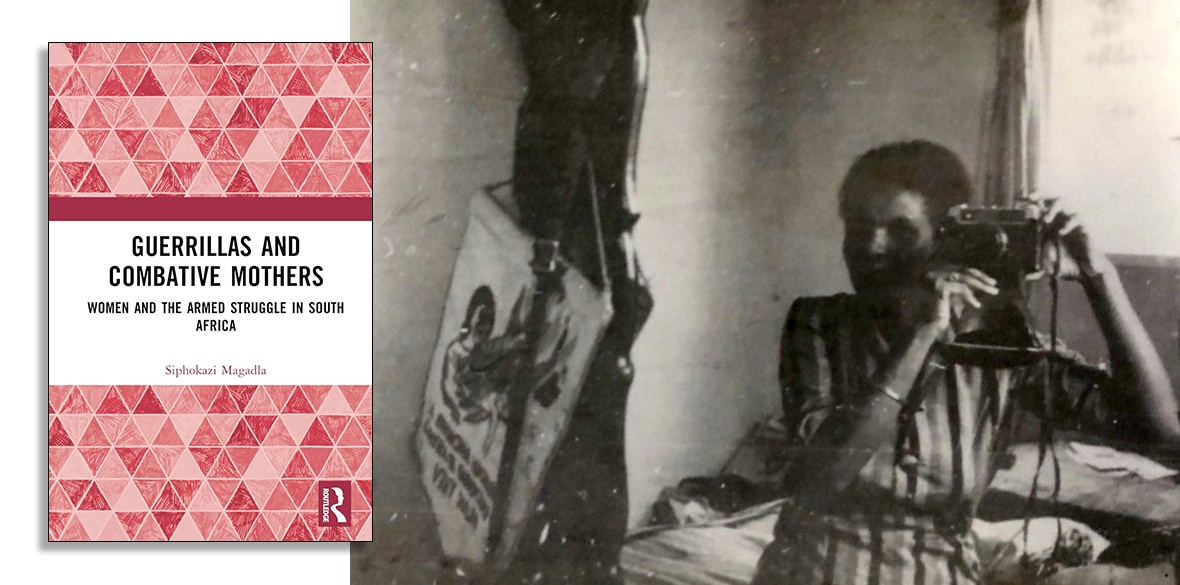

That women, fighting patriarchal structures at every moment, were central and essential to that struggle, both as combatants within the various guerilla armies and as politicised agents in the population, is the history that she lays out in her landmark new book Guerrillas and Combative Mothers, Women and the Armed Struggle in South Africa (Routledge, £130). That struggle continues: looking forward to 2063 and the centenary of the Pan African Movement: “We can’t get the Africa we want,’ she says, “if it’s still patriarchal and homophobic.”

Following the Sharpeville massacre on March 21 1960, both the five-decade-old African National Congress (ANC) and the newly formed Pan African Congress (PAC), after discussion with their allies and particularly the SACP, renounced their long-held commitment to non-violence. Alongside policies of international solidarity and mass mobilisation came the armed struggle and, in 1961, the guerilla army uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK, “the Spear of the Nation”) was formed with Nelson Mandela as the first commander.

“What the book does,” explains Magadla, ”is to explore what women made of this moment.”

To assemble the broad picture she interviewed 40 women who trained for combat with MK, Amabutho (a township-based paramilitary force in Gqeberha, formerly Port Elizabeth), and Poqo, the armed wing of the PAC.

Her discoveries are startling, and their implications far-reaching.

While women were outnumbered by men in the paramilitary forces they were, nevertheless, singled out from the start for leadership roles. She cites Ruth Mompati, a founding member of the Federation of South African Women and one of the organisers of the 1956 Women’s March in Pretoria. In 1962 MK sent Mompati for military training to the Soviet Union before active service until 1994, after which she served as an MP, as ambassador to Switzerland and as executive member of MK’s Veterans Association.

If Mompati was part of the first wave, following the Soweto Uprising of 1976 recruitment to MK exploded in number and the need for gender quality pressed urgently on the organisation.

Many women, coming from the “black consciousness” movement of Steve Biko and others, were central in introducing gender equality to both the ANC and the MK. When it came to training for combat the gender difference was completely overlooked, but to maintain the militias the MK was forced to address the material and reproductive needs of women.

“The harshest conditions were experienced in the 1970s,” says Magadla, “but laid the ground for women who joined in the 1980s to have a better experience.”

Particularly fascinating is the essential and unique role that women played in combat. “They combined military training with a dynamic use of femininity,” say Magadla.

So, for example, Busisiwe Memela who was sent to be trained in Cuba and is now CEO of the South African Social Security Agency, played a vital role in Operation Vula in 1988. The purpose was to infiltrate ANC leaders and weapons covertly into South Africa and this couldn’t have happened had she not found a way to make undetectable reconnaissance of the the border crossing. To understand the habits of the guards she dressed as a Swazi domestic worker and took advantage of the inbuilt patriarchal blindness of the soldiers.

Another famous example is that of Thandi Modise, one of the most successful guerilla operatives, who disguised herself simply by knitting.

Eventually it became essential to recruit women rather than men for certain roles because they would not be suspected to be combatants.

More numerous, however, than the women who went into exile and are the most visible female guerillas, are the vast majority of women who remained in South Africa and whose role is misrepresented.

“What I try to show,” says Magadla, “is that the militancy of a woman like Winnie Mandela is not the exception. What I term ‘Combative Motherhood’ was really the rule. These were not women who got involved in the struggle because their children were getting harassed in schools and in their homes. These were women whose ideology aligned with the politics of the United Democratic Front.”

She contests the “conservative articulation of motherhood” of other historians like Shireen Hassim, and quotes Baleka Mbete, later speaker of the National Assembly and deputy president of South Africa:

“I remember an early morning, before I went into exile. My son was on the breast. But a comrade arrived because we had to go somewhere. That was the reality of underground work. I had to pull my son from the breast...”

She also quotes Zoleka Mandela’s memoir When Hope Whispers:

“By the time I was born on April 9 1980, my mother knew how to strip and assemble an AK 47 in exactly 38 seconds.”

When, in the 1980s, the ANC introduced its policy of ungovernability and people’s war, the contemporary media and historians have focused on young men, the “young lions.”

“But,” says Magadla, “the young lions relied on the material and ideological support of their mothers.”

So — given this active role, why is the history of these militant women threatened with erasure?

As Magadla explains, this is because the majority of female combatants couldn’t integrate into the new South African National Defence force, the state security organisation that amalgamated the MK, Poqo and four armies from the Bantustans with the old SADF. Suddenly there was the requirement for an educational qualification they didn’t have, and they found themselves ranked much lower than expected. Either that, or those who had fought were paid off at a derisory rate.

And so, “in the main, former guerillas are poor, like the majority of South African women,” says Magadla, “and can be found in the margins of the neoliberal economy that relies on cheapening women’s labour. They are domestic workers. They are grandmothers.

“This is similar to the experience of women in Zimbabwe, Eritrea, Namibia and Mozambique. Women guerillas are told to shrink themselves, after liberation. To become feminine.”

And,” she continues, ”I hope the book shows the process by which we have arrived at a certain kind of gender architecture. The broader question now is how to transform this post-colonial Westphalian state system and neoliberal economy, that I cannot see Africans transforming, let alone decolonising.”

Nevertheless, the SANDF has a code for gender equality and that happened because women made it happen. It is no mistake that women like Jackie Sedibe rose to be major general in the SANDF and was instrumental in ensuring that women participate in all arenas. Nor that four women lead foreign policy, with someone as fearlessly outspoken as Naledi Pandor taking a leading role, and who is one of the architects of the recent ICJ case.

“We must understand her as belonging in a tradition of women who were involved in the anti-apartheid struggle, who believed that when democracy arrives the state can be transformed to meet the needs of women.”

But, despite the presence of such prominent figures, Magadla has no illusions about the persistence of deep inequalities in contemporary South African society. So, where are the radical women today?

“Today, sadly, the ANC is dysfunctional and near its end. We have to look again at the social movements like we did during the national liberation. It was only in 2019 that the South African state was made to admit that this is a femicidal society where it is dangerous to be a girl or a woman.

“And it was made to admit that by women in the social movements, who lead shutdowns of university and government spaces. That’s where we get a glimpse of what a radical future can look like. We have to look to that, and certainly not to the political parties that we have in this election year.”