This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

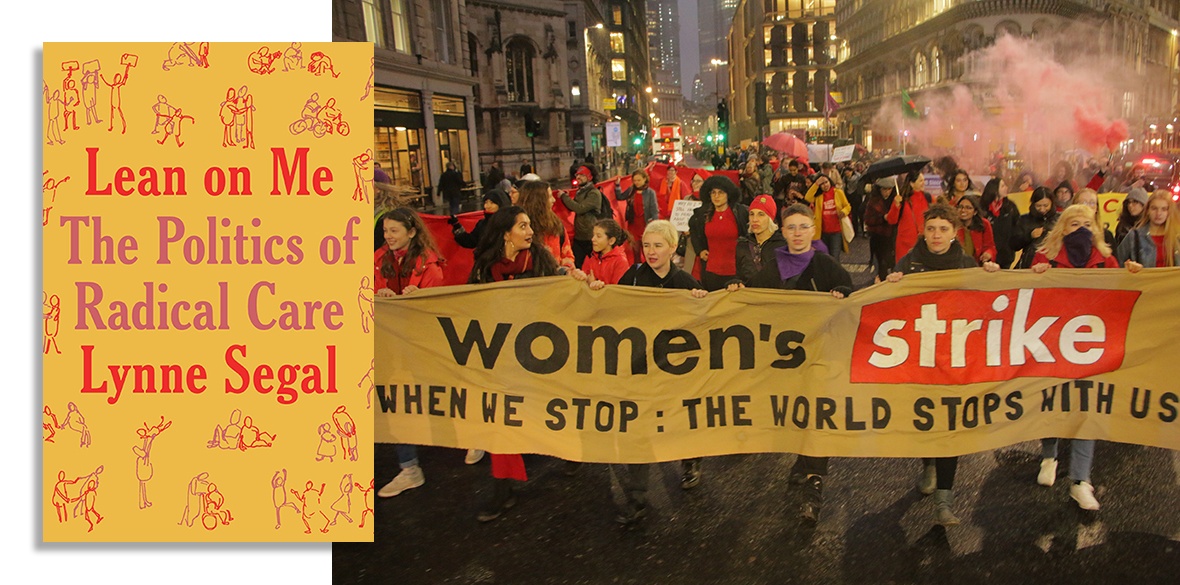

Lean on me

Lynne Segal, Verso, £17.99

AS Lynne Segal explains in her introduction, this book revisits her own personal and shared history, while invoking “those powers of collectivity which provide the only energy that keeps hope alive, however grim and alarming our own times may seem.”

This is not just a personal autobiography then. Lean On Me is the story of social movements and their political contexts, recounted by a socialist feminist who has been, and continues to be, deeply involved as an activist as well as an academic. The result is an engaging and thought-provoking book, affirming human interdependence and care for the environment at the heart of a politics of hope.

The first chapter focuses on the family and motherhood, exploring Lynn Segal’s personal experiences in the context of debates within second wave feminism.

Socialist feminism had been the predominant trend at the time, she explains, although this began to shift, with the rise of the political right in Britain and the US in the 1980. So many women’s options shrank in the context of dwindling public services and greater financial need, with neoliberal austerity policies impacting most severely on single parents and poorer women.

Meanwhile those who could afford individualised solutions, outsourced their caring responsibilities to others — employed in low-waged and precarious jobs. Despite the formidably greater obstacles in the current political context, many young women were coming to similar conclusions, campaigning for a reduced working week, the reversal of welfare cuts and increased public funding for childcare provision.

There had been spaces for challenging mainstream approaches, in the 1970s, including the racism that blighted African Caribbean children’s schooling, for example. But spaces began to shrink from the ’80s onwards.

Segal posed her own challenges to mainstream approaches, questioning psychology’s focus on the behaviour of rats in experimental conditions, rather than focusing upon understanding humans within their social contexts. She herself survived job cuts that accompanied the “reforms” of the Thatcher era, and their continuation under New Labour. But she was in no doubt about the destructive effects of marketisation more generally, emphasising the importance of struggling to build and sustain more caring and more critical educational practices at all levels.

Divisions deepened in the ’80s, in fact. Segal includes references to the emergence of neoliberal feminism, focusing upon professional women’s concerns, along with the assumption that gender equality had been achieved by the late ’90s and was now evident in women’s happy embrace of consumer culture by that time. This has, of course, been challenged more recently with the resurgence of feminism in Latin America and elsewhere, as Segal goes on to point out.

The third chapter, A Feminist Life, focuses on feminism and women’s struggles more specifically, starting with the predecessors of second wave feminism, including Eleanor Marx and Sylvia Pankhurst.

Subsequent chapters explore issues of vulnerability and interdependence through the experiences of the disability movement, along with the challenges of ageing, against the background of so much negative stereotyping.

The book concludes with a chapter on Repairing The Planet, including reflections on the writings of Marx and Engels (too often dismissed as having ignored environmental questions), followed by the final chapter on Caring Futures. Despite being only too well aware of the obstacles to be overcome, Segal points to the possibility that more hopeful futures could be possible, referring to the potential contributions of movements for climate justice, for example, along with the return of the feminist left.

Lean On Me is a very accessible book. Academic and political sources are cited and evaluated, but there are clear explanations, and the result is a wide-ranging text, with plentiful evidence — and personal illustrations — to support the author’s conclusions.

Readers who are old enough to remember the struggles of the ’60s and ’70s should find this a really engaging reminder, whatever differences they may or may not have had, in the past. Younger readers should also appreciate these histories’ continuing relevance in the contemporary context.