This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

FIFTY years ago, in the autumn of 1972, thousands of construction workers were returning to building sites for the first time in three months, with a spring in their step and more money in their pockets.

They had just achieved what many thought impossible; a national strike across a fragmented workforce, resulting in the biggest pay rise the industry had ever seen.

It was the first — and only — national builders’ strike in British history. At the height of the action, unions reported that 200,000 workers at 7,000 sites had downed tools. The offer marked a major victory, not only for the construction workers, but the trade union movement.

However it was a victory that the bosses, and their Tory cronies, could not swallow.

For a group of 24 construction workers in North Wales, the high of their successful strike action was short lived.

Five months later, police came knocking on doors with a long list of bogus charges alleging violence on pickets.

The following trials of the Shrewsbury 24 would go down in history as one of Britain’s biggest miscarriages of justice — and a cautionary tale to all those fighting for better pay and conditions of how far the state will go to silence the trade union movement, one that remains as relevant today as ever.

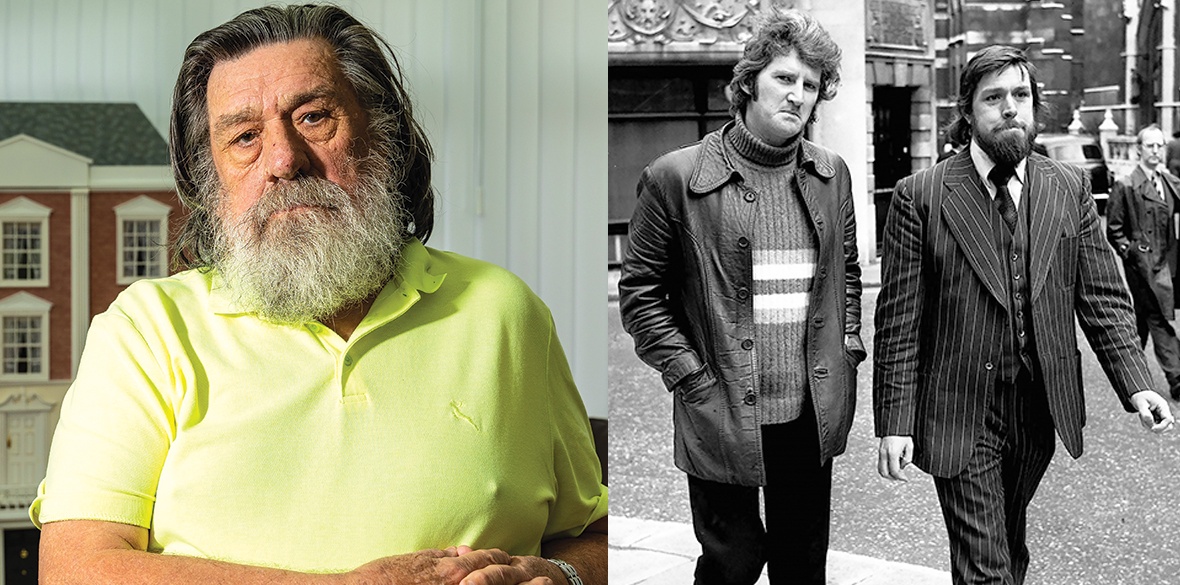

Among the pickets put on trial was veteran actor Ricky Tomlinson.

Before his award-winning career in show business, the Royle Family star worked in the building game as a plasterer, and was a strike organiser in the 1972 walkout.

He was jailed for his part in the strike, along with his dear friend Des Warren, a steel fixer and fierce trade unionist. I went up to visit Tomlinson in his home city of Liverpool to chat to the former construction worker about the events all those years ago, and why they’re still important today.

We sit in the conservatory of Tomlinson’s suburban home, where he lives with his wife, and agent, Rita, surrounded by grinning photos of his children and grandchildren.

Reclining on a cream white sofa, the actor, now 83, recalls the scandalous episode that still enrages and haunts him to this day.

A strike to save lives

Like thousands of workers, Tomlinson tells me he joined the strike in 1972 in the hope of improving the dangerous and dehumanising conditions they were forced to work in day in, day out.

“In 1972 when we went on strike, someone got killed every day,” the Liverpudlian, who was living at the time of the historic walkout in Wrexham, north Wales, with his wife and two children, says.

“Every day there were widows and orphans left because of the conditions on the builders’ sites. It was outrageous.” Horrific cases of builders being crushed by falling machinery, or plummeting to their deaths from poorly secured buckets down tunnel shafts, were unfortunately all too common. The year before the national builders’ strike, there were 201 fatal accidents, and over 70,000 reported serious injuries.

Life and limb were seen as cheap. In fact if an employer was taken to court over a death on site, the penalty was a mere £100 fine, as Tomlinson says: “They put the price of a building worker’s life at £100.” Conditions were also horrendous: “The last job I worked on where we all ended up going to jail was the Wrexham bypass … and there was two toilets for 200 men,” he recalls.

“Yet the general foreman and all that, they had a hut with hot and cold running water, flush toilets, somewhere to sit.”

Eventually, builders decided they’d had enough of living on poverty wages (the basic rate for skilled workers was just £20, and for labourers, £17, for a 40-hour week) and fearing for their lives at work.

They walked off sites, demanding £35 for a 35-hour week and an end to the “lump,” a casualised group of non-union labour who were given a lump sum without holiday, National Insurance contributions or sick pay.

On September 18, the strike was called off after union negotiators accepted an offer of a new basic rate of £26. While the full set of demands was not met, resulting in many activists opposing the settlement, the agreement was nonetheless considered a great victory, with some workers receiving a 50 per cent rise — an offer almost unimaginable today.

“It terrified the bosses”

“The strike was so successful that it frightened the life out of bosses,” Tomlinson growls, as he recalls how the wounded construction giants launched an attack on pickets.

After the strike was called off, the National Federation of Building Trade Employers put together a dossier alleging violent incidents on picket lines, which Edward Heath’s Tory government was only too keen to act on.

During the strike, Tomlinson was part of a group of trade union activists on the Wrexham strike committee who organised peaceful pickets around north Wales.

On September 6, around a week before the strike ended, 300 men jumped into coaches and headed to Shrewsbury, where many sites were on the lump and still working in a bid to convince them to shut down — a tactic known as flying pickets.

Despite the fact there were no arrests and no cautions made on the day, 24 men involved in the picket that day were put on trial, six of whom, including Tomlinson and Warren, were charged with conspiracy to intimidate (an arcane offence not used since Victorian times) affray and unlawful conspiracy.

Tomlinson describes the trial that followed in no uncertain terms: “The case was ridiculous, it was absolutely ridiculous. The trial lasted for 55 days.

“I was in the witness box for three days. In today’s money it must have cost between £20 and £30 million. The security was bigger than any trial I know of, and I’m talking about criminal cases where gangsters were on trial. There were hundreds of police.”

The proceedings were mired by suggestions of outrageous state interference, including a puppet judge and attempts to mislead the jury.

By the end of the three trials, six trade unionists were sent to prison, 17 pickets received suspended sentences and only two were acquitted. Tomlinson received two years, and Warren was convicted on all three charges and went down for three years.

“We weren’t going to soldier”

In protest at their incarceration as political prisoners, Tomlinson and Warren refused to work or wear clothes, defecated on the floor and went on hunger strike.

Their protests were met with severe punishments, including solitary confinement. Warren was repeatedly drugged in a bid to keep him under control, and the pair were moved repeatedly from prison to prison.

During their hunger strike, prison officers tried to trick the pair into eating food by claiming the other had caved. But the old friends’ trust in one another was unwavering, and they refused to back down.

Tomlinson recalls seeing Warren in the prison yard for the first time after their gruelling hunger strike. “He [Warren] was very dour you know, I loved him but he never laughed,” the actor tells me.

“I think that was one of my strengths, I could find something funny in almost any situation.”

But the sight that greeted the steel fixer in the prison yard that day — a semi-naked Tomlinson draped only in a blanket around his shoulders, with his hair and beard down to his chest — was one of the rare moments he did see his friend crack a smile.

“Dezzie is already standing in the prison yard and he said: ‘My God, you look like Ben Gunn out of Treasure Island’!” He erupts into that loud, deep and infectious laughter, the hallmark of his alter-ego Jim Royle, momentarily drowning out the shouts from a football match in full swing in the field next door.

Blacklisted

After his release, Tomlinson and the other pickets continued to be punished for daring to demand better wages and conditions, finding themselves blacklisted.

Unable to get a job, he lost his home and fell into poverty. After a few odd jobs, he never worked in the building industry again. But by some strange twist of fate, it was the bosses’ blacklist that drastically changed the direction of Tomlinson’s life, as he turned his hand to acting instead.

He tells me how he turned up to one of his first auditions with holes in his shoes and bloodied feet, having walked halfway across London because he could not afford the fare for the Tube.

But it wasn’t long before Tomlinson’s acting career took off, later starring in Brookside, the Royle Family and two films directed by Ken Loach (one of Tomlinson’s one or two heroes) to name a few, becoming the comedian, TV star and award-winning actor he’s widely known as today.

As he notes: “I’m one of the lucky ones… I’ve had a good run.” It’s a life Tomlinson could never have imagined all those years ago kneeling on wet planks on sodden building sites, and less so during his gruelling months behind bars.

“Never, never would have imagined, kid,” he replies, shaking his head. “Never imagined when I was lying there, in the nude, counting the bricks in the wall and cracks in the window.”

But over the decades, Tomlinson, the pickets and their families never gave up the fight for justice. In 2004, their campaign took on a new urgency after the death of Des Warren.

The state killed my mate

Warren died at the age of 66, after suffering a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. Tomlinson and Warren’s family are adamant that the cocktail of drugs he was given in jail contributed to his death. “He was a strong character but they were destroying him bit by bit.”

Seeing his dear friend, once a broad and strong steel fixer, barely able to hold himself up in the final moments of his life, still brings Tomlinson to tears.

“I was told to go to see him. I went in,” the 83-year-old pauses as tears well up in his eyes, “…and this lad, this giant, was lying on a mattress on the floor. He was as white as a ghost, his hair was snow white. He had a rope from the floor going into a beam in the ceiling and he pulled himself up and put his arms around me and kissed me. That was the last I’d seen him.”

Almost five decades on, Tomlinson remains deeply affected by his experiences in jail, and the cruel treatment his friend suffered.

“It’s stayed with me, and sometimes it comes back to me when I don’t want it to,” he says. “When I’m trying to think it always goes back to him lying on that bloody thing on the floor. It’s awful.”

Convictions overturned - justice at last?

That’s why, for Tomlinson there can never be justice for the suffering inflicted on the pickets by the state. After 47 long years, in 2021, the Court of Appeal quashed the convictions of the Shrewsbury pickets.

While the verdict was widely celebrated, Tomlinson argues that “nothing can do right what they did to us.”

“We’ve known from day one that we were innocent and so did the legal system. You see our Establishment is very very clever, and they knew that sooner or later everyone would know it was a put-up job. Now they can say: ‘Ah yes, we’ve made a mistake, we’ve rectified that mistake.’ They didn’t say we’ve killed Dezzie Warren in the meantime. They’re clearing their own conscience.”

Meanwhile there’s been no acknowledgement that pickets’ telephones were tapped, he says, or his firm belief that Edward Heath’s government colluded with security services and the police to ensure they were locked up.

This lasting injustice is compounded by the state’s refusal to disclose many of the Shrewsbury files, which remain classified under national security laws to this day.

“You know the wicked part about this?” Tomlinson asks. “They’re never going to release the papers because it’s under section 23; a threat to national security. Can one of your readers, I’ll give them a fiver or a tenner if they can tell me, how a building workers’ strike is a threat to national security?”

Legacy of the builders’ strike

Looking back at the builders’ strike 50 years on, Tomlinson tells me he would still do it all over again. Conditions are “tens times better” than what they would have been had they not walked out all those years ago, he says.

Health and safety improved, for the first time workers were given proper wet weather gear. But he notes that the fight is far from over.

In 2022, builders are still working on sites without proper toilets, a place to have their meals or wash their hands. Meanwhile many of the problems the Shrewsbury pickets were fighting against in 1972 still exist to this day.

The lump lives on in the form of the gig economy and bosses continue to make bumper profits off the backs of workers living in poverty.

With Truss’s Cabinet preparing a fresh round of anti-union laws to squash a new wave of national strike action, Tomlinson is reminded of the events in 1972, when Heath’s government passed the anti-union Industrial Relations Act.

“In this country it’s still us and them,” he says. “It’s still us and them and this has probably never been more noticeable than now. The divide is getting deeper and wider and bigger. I never thought in my lifetime when a pensioner would have to decide whether to heat or eat, they never even had to do that in the war.”

At 83, Tomlinson’s anger at social injustice has by no means dulled, as he rails against the push for driverless trains (“It’s bloody ludicrous!”), the vilification of striking refuse workers, and bosses’ ceaseless attempts to skimp employees’ pay.

But he’s hopeful too, warning that Truss has a fight on her hands in the face of a resurgent trade union movement. “I think she’s got a far tougher job on her hands now, with the likes of Mick [Lynch], Mark Serwotka. I genuinely think that within the next few months we’ll see people out on the street. And you can tell her from me, I’ll be right at the front, with me placard!”

As the workers launch a new round of nationwide walkouts, I ask Tomlinson what activists on the picket lines today can learn from the events of half a century ago?

“Unity is strength,” he replies. “They’ve got to be together, they’ve got to sing off the same hymn sheet, have the arguments, have the pros and the cons. But when they come to a decision, they stick by it and they don’t fragment — that’s so, so, so important.”

Bethany Rielly is the Morning Star's Home Affairs reporter. Follow her @bethrielly

Bethany Rielly

Bethany Rielly