This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THIS YEAR, March 25 would’ve been Blair Peach’s 79th birthday. Except on April 24 1979 he was killed by a police officer with what was then called the Special Patrol Group (SPG) in south London’s Southall after returning from an anti-racist demonstration.

Peach’s story is unfortunately not an isolated one — he wasn’t the first young anti-racist demonstrator killed “for a simple gesture of solidarity,” as one Southall resident put it, and he is by no means the last.

But Peach’s story is a remarkable one, because it is one that has left such an extraordinary legacy, one which finally opened up conversations about police brutality — especially within the excessively violent SPG — and the lack of accountability from a police force when their officers abused their power.

These were of course conversations that people of colour had been having for decades.

Peach’s partner Celia Stubbs was at the forefront of the fight to bring those who killed Peach to justice. And it’s through her vast archive of legal documents, newspaper clippings, campaigning material and other ephemera that Peach’s legacy lives on at the Bishopsgate Institute, where she has just donated her collection relating to her decades-old battle.

Included in this archive is the founding of Inquest in 1981 — Celia was a key figure — and its ongoing work on state-related deaths, as well as papers relating to the spycops probe, of which Celia was a victim for over 20 years.

Flyers for meetings, correspondence to solicitors, fundraising appeals and letters of solidarity to other bereaved family members of victims of state violence are stark reminders of the exhaustive work and the relentless agitation it took Stubbs and other campaigners with the Friends of Blair Peach Committee in their battle.

A scrapbook of Celia’s newspaper clippings spanning over 40 years reveals the extent of the news coverage surrounding not just Peach’s death, but also the seemingly endless legal battles which followed it.

The news even travelled as far as New Zealand (Peach was a New Zealander after all), and also included are newspaper articles from the Morning Star, as well as writings from the Star’s own prolific jazz correspondent Chris Searle.

Witness statements from that fateful day held in the archive confirm the policemen’s involvement in Peach’s death, yet despite an early investigation led by Commander John Cass concluding that an officer within the SPG killed Peach, that report would take decades and a long legal battle to get published.

And perhaps one of the most significant documents in the archive is the long-awaited Cass’s Inquiry report.

Tragically, the publication would come off the back of another disturbingly similar incident with a brutal arm of the Metropolitan Police: the death of newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson following an altercation with Territorial Support Group officer Simon Harwood at the 2009 G20 Summit protests.

Tomlinson’s death spurred renewed — and successful — campaigning for the release of the report and, while much of it was redacted, it’s an admission that as Celia and Peach’s supporters already knew, Peach was killed by a police officer.

Criticism of the police had not died down in the 1990s, and the Met’s racist attitudes and corrupt behaviour were once again starkly exposed after the murder of Stephen Lawrence.

Stephen’s family’s own fight to bring his killers to justice was also unbelievably gruelling and relentless. And Celia’s archive includes letters from the Lawrence campaign inviting the Peach organisation’s participation in the People’s Tribunal on Racial Violence and Justice, exactly a year after Stephen’s death.

Like Celia, Stephen’s family intended “to use all means available to us to ensure justice for Stephen.”

More recent documents relate to Celia being targeted by the infamous spycops operation, under surveillance for 20 years.

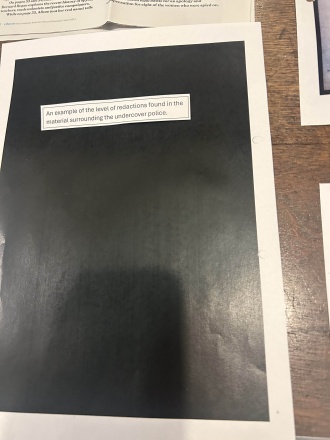

The papers requested by her relating to the operation sitting in the archive are so heavily redacted it would be laughable if it wasn’t so insulting. One sheet of paper is entirely redacted, with a note (from Celia) stating: “This is an example of the level of redactions found in the material surrounding the undercover police.”

It’s an extraordinary archive, charting a bitter battle not only for justice for Blair Peach but all the campaigning work of other families who have lost loved ones over the years in such violent circumstances.

Alongside the Peach collection, the Bishopsgate Institute is home to the archives of several organisations and individuals that have challenged state violence and impunity.

Inquest’s vast archive includes over 70 boxes of material exposing its long battles for fairer investigation systems (including the provision of legal aid), better treatment of bereaved families, and its challenge to the way that state impunity, cover-ups and false narratives have thwarted the possibility of meaningful justice.

The Bishopsgate Institute is free to attend and open to everyone, located at 230 Bishopsgate, EC2M 4QH. The Researchers’ Area is open 10am-5pm, Monday to Friday, with late opening on Wednesdays. If you have any enquiries about attending, email enquiries@bishopsgate.org.uk.