This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

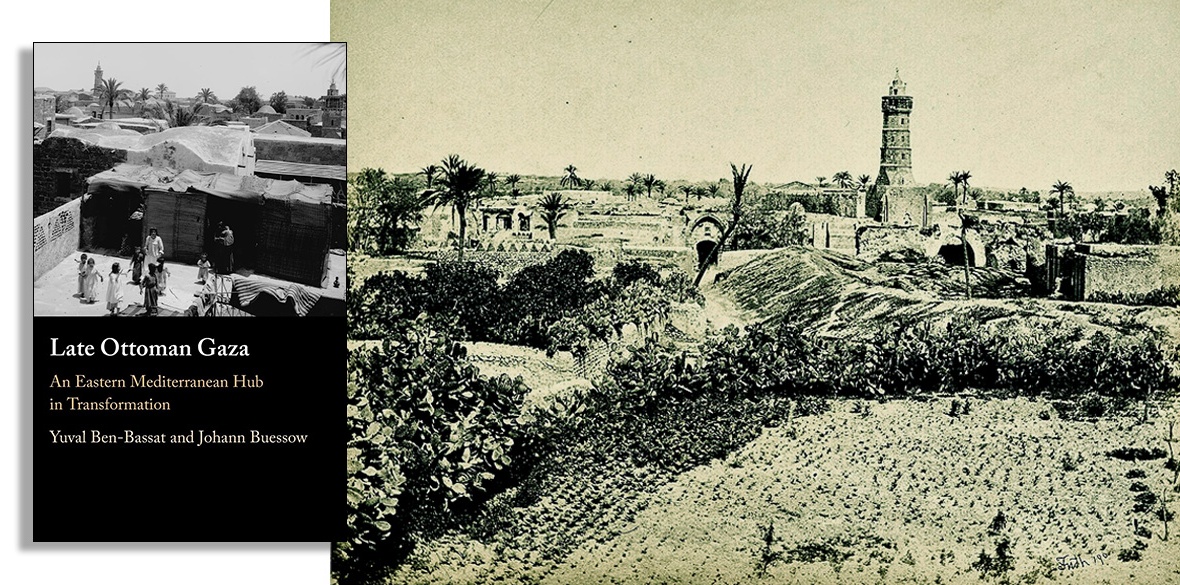

Late Ottoman Gaza: An Eastern Mediterranean Hub in Transformation

Yuval Ben-Bassat and Johann Buessow, Cambridge University Press, £85

YUVAL BEN-BASSAT and Johann Buessow are the sort of historians who like digging through archives for granular detail. Ben-Bassat’s previous work includes a study on petitions sent from Palestine to the Ottoman sultan at the end of the 19th century. Buessow’s CV includes the work Egyptian Rule in Syria through the Eyes of An Anonymous Damascene Chronicler 1831-1840.

This book is equally specific, delimited and detailed. This is not a history of heroes, this is what you can learn from, say, the 1905 Ottoman census in Palestine.

The manuscript was finished shortly before October 2023; the authors considered, and then rejected, updating it in the light of events since then which have plunged Gaza into the abyss. The tone is studiously academic and politically neutral, telling you what the evidence says and implies, and framing it within their particular expertise.

As such, they produce a detailed pen-portrait of Gaza before the British Mandate. Some of it is mundane detail. But the life of the many is often made of mundane facts and a place presently in the eye of the storm was not always in such distress.

The historians were unable to actually get into Gaza to do their research, which is a shame as existing historical records in Gaza are now very likely destroyed by Israel’s onslaught. However, the source material is diverse and as well as the 1905 census they examined sharia court records, Arabic, Hebrew and English manuscripts, memoirs, records and reports, both local and international, petitions, correspondence, and photographs and plans of the landscape.

Gaza in the late Ottoman period was a unique and somewhat liminal place — a coastal city that never developed into a major port like Beirut or Jaffa. It was urban yet surrounded by rural villages, with a strong Bedouin and Egyptian influence, especially before the formalisation of the Egyptian border under British rule. Neighbourhoods had their own characteristics and resident families.

Despite its ancient significance, Gaza “has never been integrated into any modern nation-state and is more akin to a huge relic of the pre-nation-state period that remains untethered and unincorporated.” This is true even now.

Gaza was primarily a hub on a major land transportation route. Indeed the road through Gaza terminates in Cairo at one end and Damascus in the other. This major trade route was abruptly abandoned in 1869 with the opening of the Suez canal and, in finding new ways to trade, Gazans started exporting barley to Britain for brewing beer. Throughout this period Gaza also had thriving agricultural hinterlands and a significant slice of the population was engaged in agriculture.

Shifting economic conditions led to changes in Gaza’s political institutions, fuelling intense factionalism. Rival groups engaged in heated debates and separately petitioned the Ottoman sultan for their causes, with no overlap in supporters. A major point of conflict was the appointment of Gaza’s mufti, who held significant influence over Islamic institutions. Ultimately, the Ottoman government abolished the role of the mufti and expelled one of the factions to quell the disputes.

Politics was not restricted to competition between elites, and Bedouins remained influential as did much of the working population with their various grievances and interests. Gazan politics was played very much by its own rules and was something of a headache for the struggling Ottoman empire. British encroachment and conquest ultimately made what was once more of an Egyptian town part of Palestine proper.

This book explores a niche but understudied aspect of Gaza’s history, likely appealing mainly to academic historians – with a steep £85 price for under 200 pages. It examines how the region’s geography and economy shaped competing power dynamics affecting its residents.

The authors note Gaza’s resilience, pointing to its post-WWI recovery. Whether the next recovery happens at all, as part of Palestine, or as a Mediterranean Singapore, or an Israeli settler conclave, remains to be seen.