This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

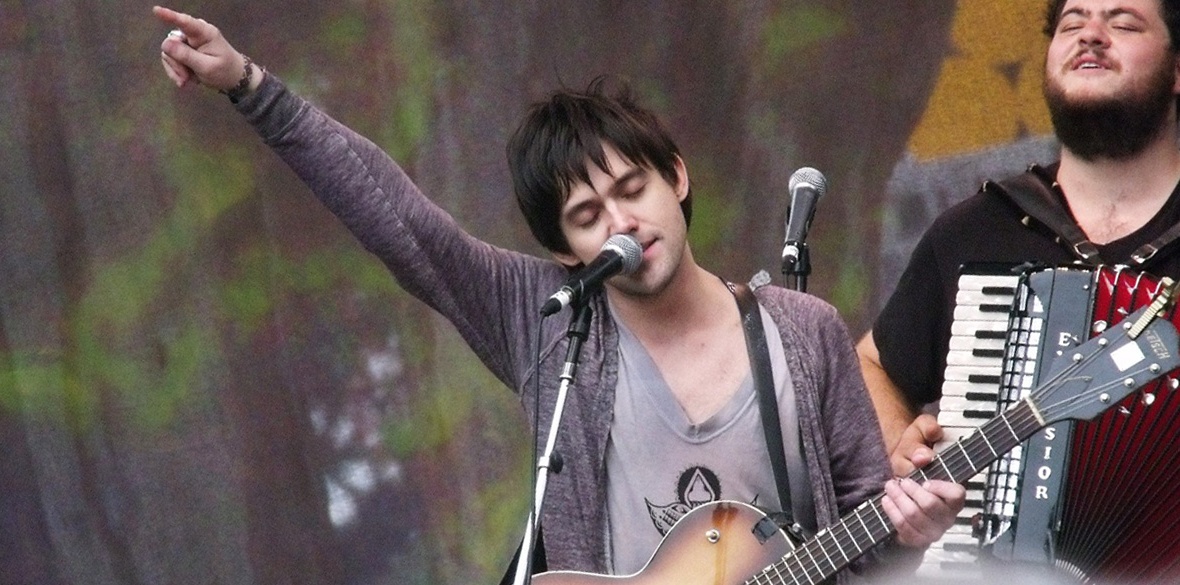

IN 2005, Conor Oberst was hard to categorise. Bright Eyes, the band he led with Nate Walcott and Mike Mogis, had just released two albums on the same day: I’m Wide Awake It’s Morning, which prompted “new Dylan” comparisons, and the electronic Digital Ash In A Digital Urn. Signed only to his brother’s DIY label, and having started out recording in his bedroom, the 25-year-old had somehow just become the first artist in eight years to occupy both top spots on the Billboard charts.

Performing on NBC’s Jay Leno should have been an easy task. But Oberst used his platform to play neither one of his chart-topping singles. Instead, he appeared solo, armed with just an acoustic guitar, to play a song he had never released. What followed was one of the bluntest and most overt protest songs of the 21st century.

In the censored clip (the song was removed from YouTube and iTunes without explanation), Oberst appeared on stage wearing a cowboy hat, seeming to parody a country musician and folk protest singer, all at once. But there was no folk earnestness in the lyrics, which drew more from the lacerating anger of Masters of War than Blowin’ in the Wind:

“When the President talks to God,” Oberst begins, “I wonder which one plays the better cop. Does he ask to rape our women’s rights and send poor farm kids off to die? Does God suggest an oil hike?”

Watching the clip 20 years later, it is hard not to think that so direct a protest song would have a much bigger struggle finding its way to a mainstream platform today (rappers Kneecap recently spoke of being blocked from raising Palestine on the Jimmy Fallon Show). It is hard to picture a songwriter from a DIY label being given such a platform to sing: “Do they pick which countries to invade, which Muslim souls can still be saved? Does he ever smell his own bullshit?”

The Bright Eyes frontman was no stranger to protest. His politics were even more explicit under his punk moniker Desaparecidos. But it was with Bright Eyes that Oberst remoulded the idea of the protest singer for the 21st century.

On I’m Wide Awake It’s Morning, which turns 20 this month, Oberst intertwines the personal with the political in a manner akin to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. But his are songs for the digital age, for a world mediated through screens and the horrors they portray. “We made love on the living room floor,” he sings on Landlocked Blues, “with the noise in the background from a televised war.” Here, the worst of the world is permitted to intrude on the life of the individual. The political becomes inescapable.

Elsewhere, Oberst chronicles growing politically awareness amongst “What history gave modern men: a telephone to talk to strangers, machine guns, and a camera lens.”

Oberst’s protest is one that rails, not just against the political decisions of the day, but broadly against the alienation of late capitalism, of life lived under a lens. Here, even the most archetypal romantic images are juxtaposed with pixellated screens: “Just when I get so lonesome I can’t speak, I see some flowers on a hillside like a wall of new TVs,” he sings at the end of Old Soul Song, recounting the disillusionment of attending an ineffective anti-war protest.

Such lyrics seem even more prescient today, where lives play against the backdrop of streamed genocides, where reels of war crimes force us to choose between cynical detachment and engaged horror. But the time in which they were written has gone. As destructive as the “war on terror” was, there was genuine outrage when its crimes were revealed. The neoconservatism of the Bush era remained predictable, classifiable, easier to protest against.

In contrast, today’s TikTok-streamed war crimes and Nazi salutes in the Capitol demonstrate how volatile our age has become. Oberst himself has acknowledged his struggle to find a way to comment on the current moment. “I hate the protest singer, staring at me in the mirror,” he sings on last year’s Hate. “There’s nothing left worth fighting for, hasn’t that come clear?”

This problem — how to engage with an age of absurdity — is one of many faced by a new generation of protest singers. With Zuckerberg’s Meta shadow-banning political content, and the Sieg-heiling Musk controlling X, even the platforms necessary for artists to share their work are at the mercy of extremist billionaires. If the protest song is to adapt, it must find a way to exist with these new spaces, whilst aiming its ire at the billionaires who run them.

Oberst, now in his mid-40s, seems to realise this. On Bright Eyes’ latest album, Five Dice, All Threes, it is not presidents, but techno-feudal billionaires who come under fire: “Elon Musk in virgin white, I’d kill him in an alley,” he sings bluntly.

Perhaps the final lesson from Oberst is that the protest song must humanise to survive. Up against the compound forces of algorithmic censorship and neo-fascism, it is perhaps not political slogans, but songs drawn from the human experience that most effectively protest at the new world’s absurdity.

On Coyote Song, penned by Oberst years before Trump’s presidency, it is a relationship which takes the lead; two lovers separated by Mexico border controls: “Loving you is easy, I can do it in my sleep. I dream of you so often it’s like you never leave, but you’ve gone below the border, with a nightmare in between.” Perhaps, it is here that the tyrants of today can be most effectively protested against: in the simple assertion of the everyday, the life lived, defiantly, up against the most anti-human forces.

For as long as there are artists who can capture this, the personal with the political, the human raging back at the machine, the protest song will never be defeated.