This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

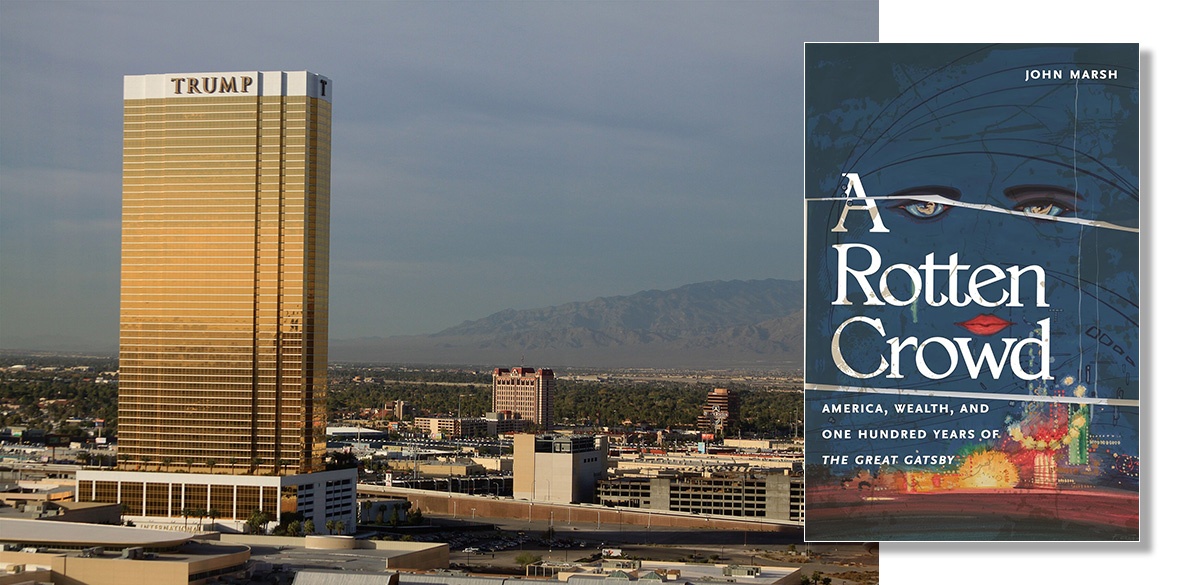

A Rotten Crowd: America, Wealth, and One Hundred Years of The Great Gatsby

John Marsh, Monthly Review Press, £16.99

AS month two of the Trump 2.0 era careens forward, reading author and English professor John Marsh’s book is a wake-up call to systemic themes and trends as he unpacks culture and the economy over a century through the lens of Fitzgerald’s novel.

He revisits an influential work of fiction to examine an enduring “popular fascination with the rich – their houses, their clothes, their manners.” At the base of these cultural features is an economic system of, by and for the accumulation of capital held together by competition and class.

Marsh draws on the insights of Marx and Veblen, producing literary criticism that blends the economic and the ideological. We get a fresh take on a 100-year-old novel that helps to contextualise the current moment of AI and anthropogenic climate chaos.

Marsh uses the lens of Fitzgerald’s fiction about the upper class and its discontents to expand our thinking about who Americans, past and present, are. The parallels between, say Nick Carraway, the narrator of the novel and Jay Gatsby’s friend, with some Americans of 2025, while not exact, are revealing in Marsh’s hands.

Clothes make the (wo)man, the saying goes. Marsh does a deep dive into the dress and the operative codes involved in the whys and wherefores of the clothes the characters wear in The Great Gatsby.

What we know as fast fashion currently, whereby some members of the working class adopt the outfits of the upper class, has its roots in the capital flight of American manufacturing abroad to the global South, an insight that Marsh develops to show the staying power of class emulation. That process is alive and well as a sign of wealth and its influence on those lacking it. Veblen’s terms of conspicuous consumption and leisure operate throughout The Great Gatsby, according to Marsh.

What we call McMansions today also stood in post-World War I America. Such ostentatious opulence produces waste, another signal of wealth in The Great Gatsby. Its characters and storyline reveal much about the class-based changes underway amid the generating of garbage and burning of coal, producing ash, in New York City.

He writes: “Waste informs The Great Gatsby in ways other than conspicuous consumption, nowhere more so than in the valley of ashes that characters pass through on their way to Manhattan and on whose outskirts George and Myrtle Wilson live. In these ashes, we can foresee the culture of waste that has irrevocably harmed our own world and threatens to harm it still more. Although no-one is innocent, including us for mimicking them, the wealthy, just as they did in the realm of clothes, bear more responsibility for this culture of waste than do others.”

In his final chapter, Marsh turns to the staying power of whiteness and white racism, noting in part how these ideologies tie into the division stratagems of an upper class whose power and privilege require the disunity of labour. Revealingly, as Marsh observes, the nonwhiteness of, say, Irish and Italian immigrants in The Great Gatsby, for starters, is a kind of glue for American capitalism. “Wealth and race belong to the same conversation,” according to him.

That is a troubling statement. Maybe the historic and multiracial George Floyd uprisings of mid-2020 point the way to a weakening of the American colour line.

Across the barricades, we see the rise of Maga. Opposites coexist.

Seth Sandronsky is a Sacramento journalist and member of the freelancers unit of the Pacific Media Workers Guild. Email sethsandronsky@gmail.com

This review was first published in Counterpunch