This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Ai Weiwei, A New Chapter

Lisson Gallery, London

DESPITE the obvious reservations about his anti-Chinese propaganda, exiled artist Ai Weiwei’s new work raises awkward questions around his own methods of production.

His Tate Modern 2010 installation Sunflower Seeds consisted of millions of small works, each apparently identical, but all unique. The life-sized sunflower seed husks were intricately hand-crafted in porcelain, each seed individually sculpted and painted by specialists working in small-scale workshops in the Chinese city of Jingdezhen. Some 100 million seeds formed a seemingly infinite landscape.

As much as a celebration of the work itself, the means of production was the central notion to the work, and the extent of the likely exploitative nature of that was questionable.

Against that backdrop his latest show in London, A New Chapter, is seemingly designed to articulate a dialogue between past and present, revealing the artist’s inquiry into the complexities of identity, politics, and cultural heritage.

First up as visitors enter the gallery are two works facing each other. One is a reinterpretation of French Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Using Lego toy bricks, this large-scale piece reimagines Gauguin’s philosophical inquiries while integrating contemporary elements such as drones and references to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The work is particularly significant for Ai Weiwei, who has expressed the lasting impact of Gauguin’s original piece on him since he first encountered it at the age of 20. By depicting himself as an aboriginal figure within this context, the artist engages in a critical examination of digitalisation and pixelation in modern art with a characteristic flair for self-promotion.

Speaking ahead of the exhibition he explained: “The palette of Lego includes only 42 colours, a limitation that, paradoxically, opens up a world of poetic possibilities for creation.”

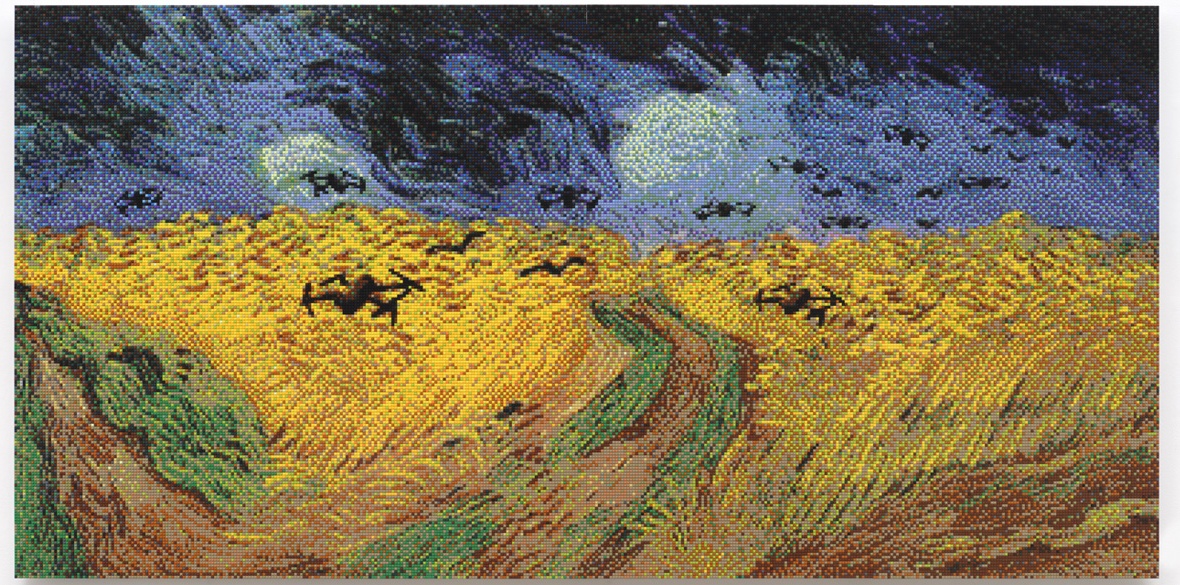

Opposite Where Do We Come From? is Wheat Field with Crows, inspired by Van Gogh’s work of the same title. This is another reinterpretation rendered in toy bricks. The crows of Van Gogh’s original painting are replaced with drones, referencing the current war in Ukraine.

This transformation reveals how historical artworks can serve as mirrors reflecting war. An apocalyptic interpretation of both these works can be made, yet they emphasise both a playful approach and a high intellectual level.

Moving into the main exhibition space, visitors encounter the large room containing the work F.U.C.K., an installation that uses buttons sewn onto four second world war military stretchers to spell out the provocative word. The buttons were collected from the now-closed Brown & Co Buttons factory, resulting in an array of more than 9,000 varieties.

This piece is intended, it seems, to signify extensive research into industrialisation, textile history and notions of military casualties. The careful arrangement of buttons underscores themes of existence and disappearance.

Another provocative work is titled Go F**k Yourself, in which the upper sections of military tents are sewn with buttons, making a comment on political polarisation and contemporary discourse and highlighting a cultural moment where conflict is often articulated in stark, blunt terms. Designed to resonate with current societal tensions it encourages visitors to confront the fundamental realities of communication in a fractured political landscape.

Continuing through the gallery four smaller-scale works crafted from toy bricks are on display. Iron Helmet Secured by Toy Bricks is an installation consisting of a rusted iron German soldier’s helmet housed within an altar-like structure made of white toy bricks. The poignant juxtaposition of materials invites further contemplation on themes of war, memory, and the passage of time.

In the exterior courtyard of the Lisson Gallery is the sculpture Iron Root 2023. Biomorphic forms seem to have spring from the foundry furnace, a criss-crossing lattice of intricate steel work, suggestive of a war-torn hell-fire environment. This is a highlight of the show.

The works on display provoke and visitors are left to determine their meanings themselves and to examine their own conscience, at a time when the UK mood moves onto some kind of war footing.

Runs until March 15. For more information see lissongallery.com