This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THERE are debates that are clarifying, and then there are debates that are mystifying. This debate in India over fascism is of the latter. It is neither a new debate, nor a real debate.

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPI(M), which is India’s largest communist party (with over one million members), is preparing to hold its party congress in April. In the months leading up to the congress, the CPI(M) held state conferences to debate the issues of the day and to elect delegates to the congress. During this period, the draft political declaration was circulated.

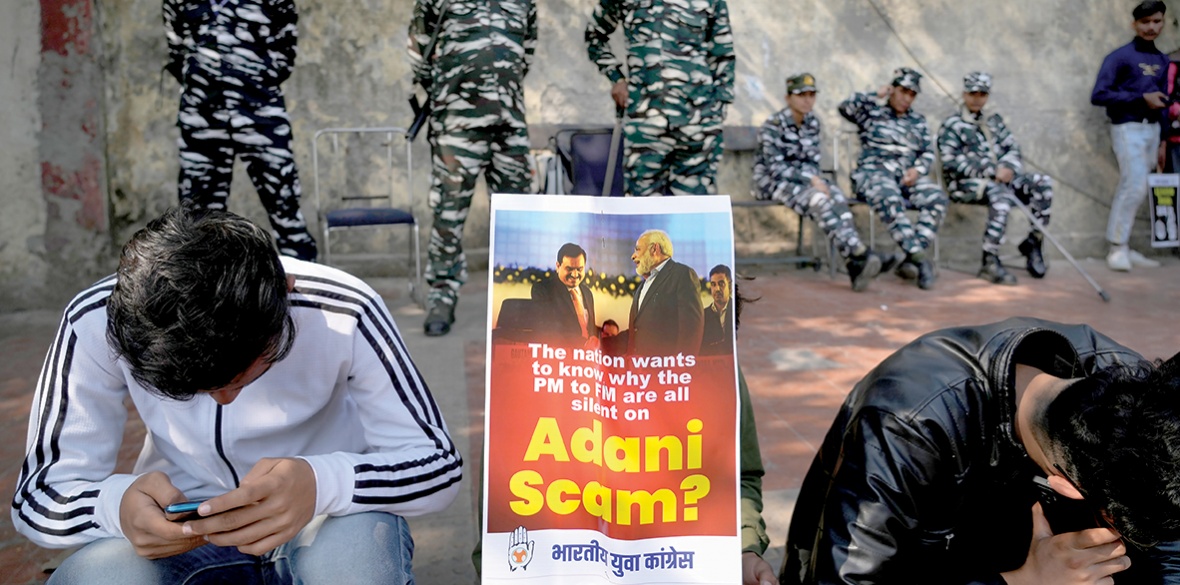

In it, the CPI(M) does not characterise the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as fascist, but as having “fascistic tendencies” and — for the first time — it referred to the category of “neofascism.” Because of this apparent non-use of the direct term “fascism,” other left forces and some left-liberal intellectuals began to attack the CPI(M), saying that the party was not clear about the role of the BJP and its three-term government in India since 2014.

What is important to immediately clarify is that no-one is saying that the CPI(M) has been lax in its role in the fight against the BJP and its Hindu supremacy, or in its defence of minority rights. The CPI(M), indeed, has led the fight — despite its general weakness in terms of the balance of political forces — against any attempt by the BJP-led government to undermine the secular fabric of the Indian constitution and to attack the rights of religious minorities and others. The issue is the non-use of the word “fascism” and the use of the concept “non-fascism.”

The BJP is not merely a political party. It belongs to a massive tentacular ecology of political forces that includes a directly fascist organisation — the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, formed in 1925) — and a range of mass organisations — including trade unions and farmers’ organisations. This ecology is known as the Sangh Parivar or the family of the RSS.

The BJP is a far-right party that has built alliances with former social democratic forces and breakaway political forces from what used to be the largest political party in India, the Congress Party. Since its formation in the 1980s, the BJP has contested elections and remains programmatically committed to the bourgeois liberal framework of Indian democracy.

This is an important reason why the CPI(M) does not consider the BJP to be a fascist party; it has demonstrated no interest in breaking with the liberal framework and has an intimate relationship with the neoliberal political dynamics that define the Indian political landscape.

On the other hand, there are several actually fascist organisations — such as the RSS and the Bajrang Dal — that are extraparliamentary hit squads, like the Braunhemden of the Nazis and the Camicie Nere of the Italian fascists.

Those groups must be dealt with in society, where they have deep roots through many decades of work in social and religious organisations. But the BJP must be fought politically, where it continues to make inroads with various political forces of the right and centre-right.

The term “fascism” has taken on a moral quality. One uses it to disparage every opponent of the right. This is a lazy quality that makes one feel good but does not necessarily produce the correct strategy and tactics for the left.

To call everyone on the right or everyone who intones a certain political discourse a “fascist” means two things: first, that there is no proper understanding of the contradictions within the camp of the far right; and second, and that there is a tendency for the left to rush to make opportunistic alliances with the liberals and the centre-right, delivering the working class and peasantry to them for their agenda when they are as often as not ready to turn around and make their own alliances with the far right when it suits them. Anti-fascism will always have a moral character, but it must not be defined by moral rhetoric. It needs political precision.

The term “neofascism” is used to explore the global nature of these developments, the linkages — for instance — between the far right of a special type in Brazil (Bolsonarismo) and the far-right Vox of Spain (extrema derecha). Certainly, the collapse of liberalism and social democracy into neoliberal austerity politics has denuded the political field in bourgeois democracies.

A small left is not able to build a working-class base to confront the utter destruction of society that resulted from neoliberalism. It was the far right of a special type that benefited, attacking parts of the neoliberal consensus but upholding its economics. This is what links Modi to Bolsonaro and to Trump. That is why that concept has now appeared.

For the left, there is no alternative but to build two things: the independent strength of the working class and peasantry to fight for a people’s democracy over the democracy of capital, and alongside that to build principled alliances with forces that are dismayed by the destruction of society and are committed to strengthen democracy.

Vijay Prashad is the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.