This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

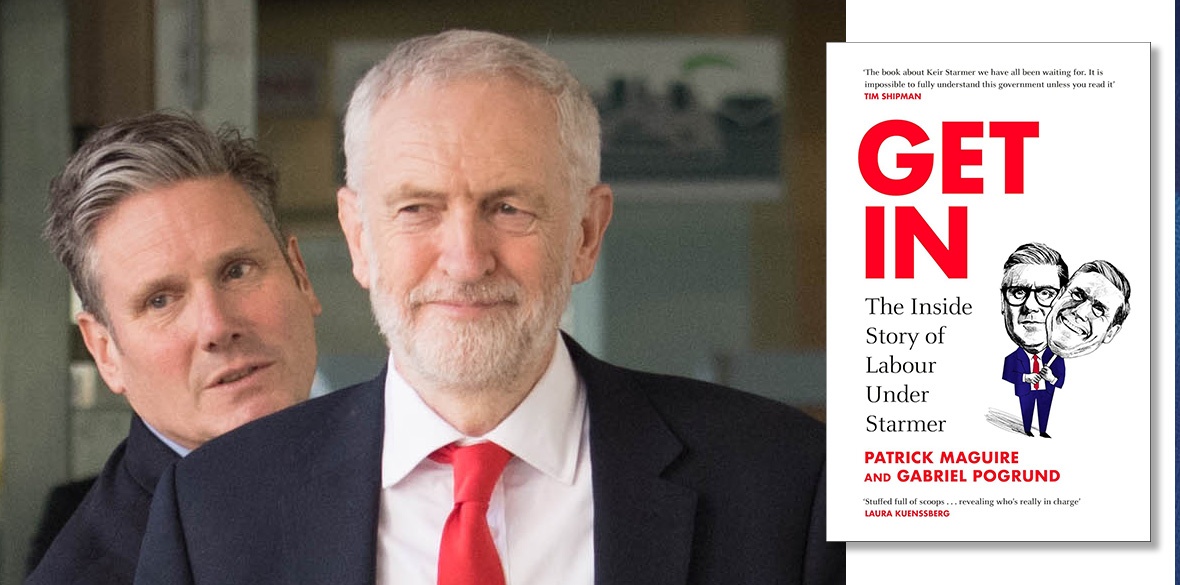

Get In

Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund, Bodley Head, £25

IF you are miserable at the state of British politics, this is not the book to cheer you up.

It implicitly poses a question: what do you call someone driven entirely by a near-psychotic hatred of the socialist left, who is scornful of trade unions, is prepared to lie and deceive to achieve political objectives, has “no regard for politicians” and panders to every prejudice to win support?

The bad news is that the answer is: the man running the country.

No, not Keir Starmer. His face(s) are on the cover, but the text within turns on his Chief of Staff, Morgan McSweeney.

McSweeney is ruthless. Nothing wrong with that, in principle. “Kinder, gentler politics” was always Corbynism’s soft underbelly, bringing a bunch of tulips to a knife-fight. However, this ruthlessness is in the service of no discernible principle. This work is subtitled “the inside story of Labour under Starmer,” which it is, but “a study in cynicism” would have worked just as well.

It is a detailed, scrupulously reported and, I would judge, almost entirely accurate telling about how we got where we are. But it is an emotionally exhausting read with – spoiler alert unnecessary – no happy ending in prospect.

Maguire and Pogrund are painstaking reporters, who follow an old-fashioned practice of writing down what people tell them and publishing it. Their previous work on Labour’s Corbyn years was scrupulous in attempting to present what Corbynism’s protagonists were about, as well as its unravelling. The book under review maintains their high standard.

Get In is invaluable for anyone wondering how on earth we got here, to a government drifting unloved, polling in the mid-20s after just nine months in office.

While it is by no means a flattering portrait of McSweeney, it perhaps takes his own successes too much at his own evaluation. The reader is taken to endless meetings where McSweeney emphasised the need to “face the voters.” Any assessment of his record must acknowledge that the latter did not very much like what they saw.

Presumably he did not anticipate winning fewer votes for Labour than Corbyn secured even at his lowest point, and three million less than his high water mark in 2017. Labour 2024 became the government elected with the lowest share of the vote in history, and close examination of the results does not even show much advance in marginal seats.

Labour’s victory depended on the shattering of the Tory vote under Johnson, Truss and Sunak, who hover in the background of this narrative like evil fairies who nevertheless shower blessings on McSweeney’s political cradle, and on Farage’s divide-the-right intervention.

It is no surprise that this book has been badly received in Downing Street. Its two principal denizens come across as a mendacious Machiavelli and an empty suit.

McSweeney engineered Starmer’s 2020 Labour leadership election victory on an entirely fraudulent prospectus. Starmer had no set convictions except loyalty to the coercive state. He would say whatever else was required. His subsequent reversals of almost every position he has ever held are now legendary. “He approached no task with the alacrity he showed when rewriting his own history,” Maguire and Pogrund write.

Starmer’s ascent shows that Labour’s right – the sediment of a social democracy not exactly a storehouse of socialist thought for generations – has, since the New Labour years, lost any vestiges of a political project beyond its will to power.

McSweeney comes across as, to say the least, unlovable. He dislikes trade unions, Unite in particular – we learn he attempted to smear it in the media as anti-semitic, without discernible impact. He describes the Labour Muslim Network as “bad faith actors,” which none would dare say about the Jewish Labour Movement. He gets abnormally excited by a Daily Mail headline declaring Starmer’s readiness to use nuclear weapons. Mad, bad and dangerous to entrust with power.

His only real stroke of inspiration was in identifying Starmer as the man on whom he could hang his project of smashing the Corbyn left and returning Labour to the bosom of the establishment. All this is told in detail, as is the shady origins of his initial vehicle for counter-revolution, the ludicrously misnamed Labour Together.

That, and his overcoming of Starmer’s initial feint towards party “unity,” forms the first part of Get In.

It rehearses in agonising detail the inability of the Corbyn team to deal with the anti-semitism issue in any way at all — painful reading for the left, which will gratify McSweeney no end since smashing socialism in Labour is what floats his boat.

At every stage in their joint progress, it is McSweeney calling the shots and taking the decisions, often contemptuous of his nominal boss.

Starmer only really comes into his own when the agenda turned to supporting the Gaza genocide. He stands resolute in opposing any suggestion of a ceasefire until Washington gives the green light. “Starmer felt instinctively that Britain’s interests, and his own, were best served by hewing close to whatever line was set by the Americans,” the authors write, precisely the attitude which destroyed Labour’s last election-winner, Tony Blair, who is a spectral and unwanted spirit haunting this tale.

The work extends into Labour’s first 100 days of office, when Starmer’s reputation for probity was the first casualty. Taking tens of thousands of pounds worth of suits, spectacles, accommodation and tickets from Labour donor Lord Alli, overriding advice that Alli should route his largesse through the party rather than putting it directly in Starmer’s pocket, turned him from sober public servant into vulgar grifter overnight.

Alli has found that free glasses don’t buy vision, as Starmer’s government has stumbled from the start, despite more relaunches in six months than Frank Sinatra had retirements.

Revelations come thick and fast. Some are unsurprising – put the news that erstwhile left journalist Paul Mason shares friends with ultra-reactionary ex-MI6 boss Richard Dearlove in that box.

Some are almost amusing – Lord Alli, when not escorting the Labour hierarchy around bespoke outfitters, paid an operative, Matthew Faulding, to stop Unite’s then legal director Howard Beckett from succeeding Len McCluskey as the union’s leader.

Faulding’s efforts passed entirely unnoticed in the union, Beckett withdrew before appearing on the ballot for a post he could never have won and the right’s favoured candidate came last.

Presumably his lordship wrote his investment off against tax.

Today, McSweeney is Chief of Staff in Downing Street, having seen the back of former civil servant Sue Gray, whose dispatch amidst chaos is detailed here.

There is little in his skillset to suggest he is equipped to run a government rather than a campaign, and nothing in his temperament to suggest he is prepared to let anyone else do so, being neither builder nor blocker but demolition contractor.

So, probably worse lies ahead, and doubtless Maguire and Pogrund will be across it. But for now the message from Get In is that a collective of the cruel, corrupt, cowardly and content-free, both vicious and vacuous, is in charge.

To the question that bothers some Star readers – is there any redeeming feature around this Labour government and the team crewing it – we have here an answer: no, nothing. Nothing at all.