This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

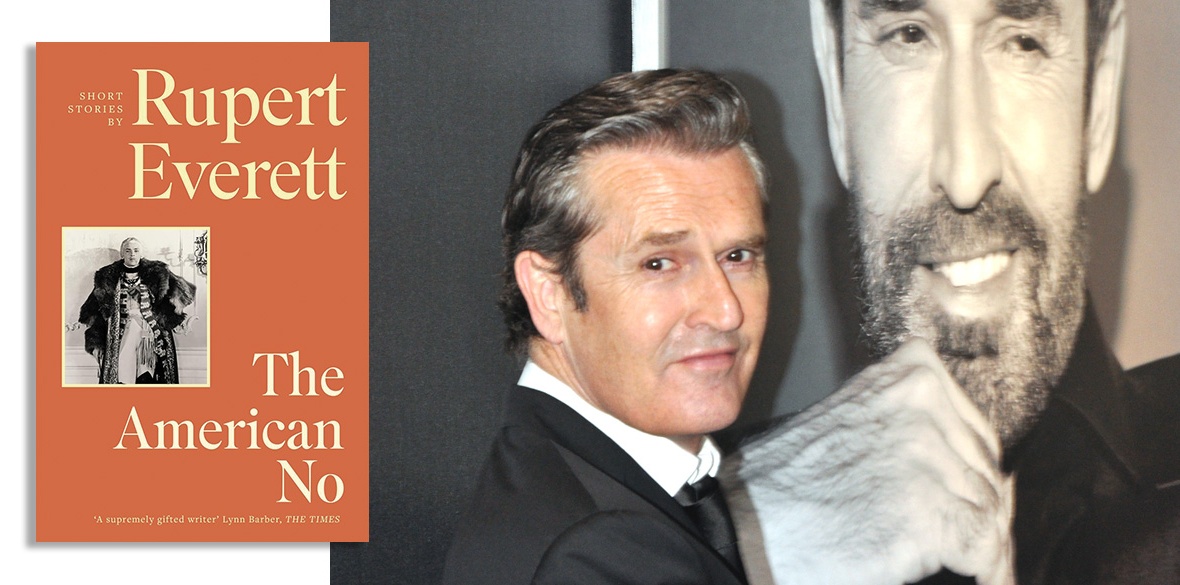

The American No

Rupert Everett, Abacus, £20

Somewhat mantra-like, the words favourite writer, gifted storyteller, literary star, writer, gifted writer, writer to his (aching) bones, sequentially appear on the jacket of The American No, a short-story collection penned by Rupert Everett.

Such peppering served to pique my awareness of clunkers like “one Sunday morning we found ourselves in the Kit Kat club as usual” and “she ran out into the bazaar, into the orange glare” and (on the loading of a hearse) “the bouncers secured the coffin to the brass rails and fastened the flowers on top before climbing in.”

Elsewhere, scene-setting sentences such as “from somewhere, the sound of dripping water” intervene questionably in paragraphs of other painterly stuff. It’s a vexatious stretch when a dense chapter’s thousand initial words pass, before we read “and that’s when our story starts.” Moreover, it might well be a story gilded with near-miss extravagances: “smoke curls from a galaxy of cigars towards the stage,” and the like. The celebrity who once fumbled the ignition of Princess Margaret’s cigarette has also failed to light these.

Further “tripwire” sentences (It’s Looney Tunes) intrude. These, I think, underestimate and even hamper a reader’s capacity for perception.

I note the availability of an audiobook and sense how the bits I found problematic will play differently when spoken. There again, realms of misconstruction and the near miss could be this author’s intended focus.

Rupert Everett’s stage performances pulse with concealed skill. His acting can seem both hyper-sensitive and coldly direct. In parallel, his involvement with cinema has been stop-and-go, often informed by absurd happenstance. In memoirs and in this current publication, he cites pitching situations where potential producers/financiers listen encouragingly to drafted proposals, then proffer a nodding promise to think it over and get back, after which a wall of “polite” silence springs up. This unspoken trigger to inertia is coined as an American “no” and it has frequently been discharged in Everett’s direction.

But he isn’t doing The Irish Goodbye. He retains affection toward his better acts of imagination and sees how these could retain existence beyond the portal of a botched conflab. Hence he now hustles his rejections into hardback.

Redemptively enough, remnants from an existential cutting-room floor are embraced, so that their cherished topics and beloved portraits achieve rescue. Some of this writing retains reality/flashback or landscape/close-up cinematic devices and there’s innovation in the form of the Proustian “The End of Time” whose text is starkly laid out as a screenplay. But Everett can’t entirely stick with this radical approach. His insights and empathies shift his compass.

Some of the stories published here are introduced by his explanations of why, in their sketched form, they were not taken up, why interested parties retracted, or how events simply conspired against purchase. Subsequent reading then becomes pleasingly layered. We immerse in a fleshed-out tale while also weighing up why its premise was turned down. We can rail against rejecting forces or read the room.

Everett’s fixation with physical decrepitude may well alienate. His hobby-horse narratives of the cellular outrage of ageing do nevertheless make sense, on these pages, as accomplice to his interest in the scandalous greasy poles and societal bear-traps that his fictional characters must negotiate. In items like “Ten Pound Poms” and “The Last Rites” physical degeneration is placed with accuracy against a panorama of historic upheaval.

Evocation of decadence also equips tales that are fictionalised out of the writer’s already well-received memoir strand.

Hemmed in by the professional exigencies of theatre and cinema, an individual’s progress is fugitive to the wishes and whims of others. Alternately, with the blank page, a writer can work up his document unbidden. Everett’s characters also seek this kind of space, their own alternative to the oppression of naysayers.