This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

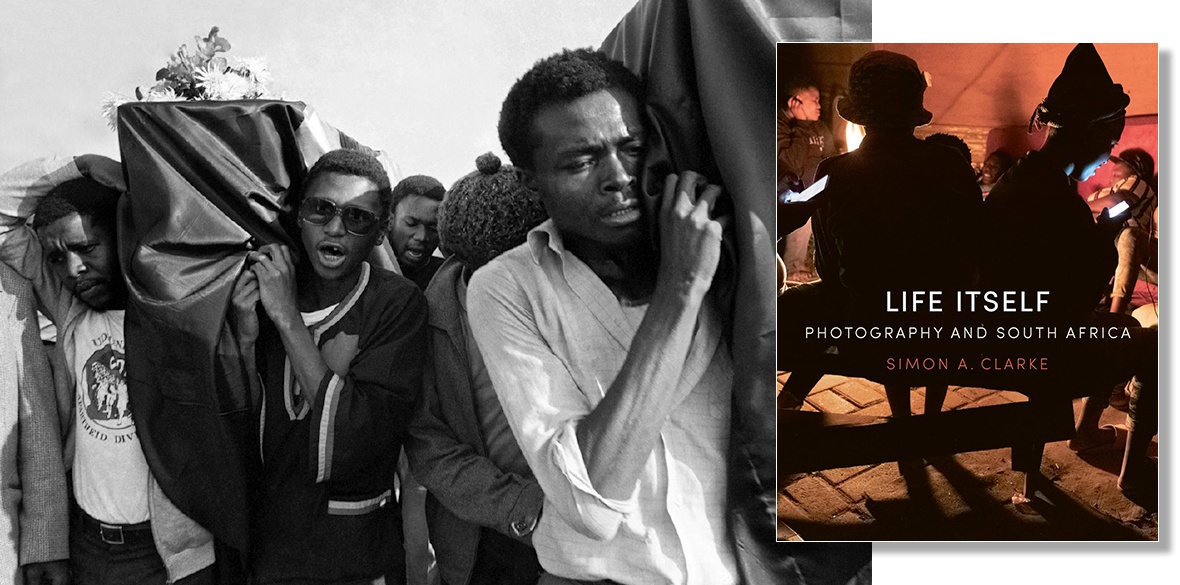

Life Itself: Photography and South Africa

Simon A Clarke, Reaktion, £35

I’M NOT an artist or a photographer, but this book does not simply look at these skills. Rather, it explores the role of the art of photography in the fight against apartheid in South Africa.

As if to help non-experts like me, the book opens with a detailed and beautifully illustrated, easily understood, explanation of the development of the technology of photography in the context of the history of South Africa.

It then poses some challenging questions regarding the use of photography to present a picture of South Africa through colonial eyes.

This is highlighted through the work of Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin who was employed as a security officer for De Beers Consolidated Mines. According to Clarke, his photographic study of the Bantu tribes of South Africa “posed his sitters to show stereotypical cultural native tropes.”

Fortunately, there are many examples of a very different photographic history of South Africa. Clarke begins this narrative by exploring the work of Constance Stuart Larrabee, who was commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar to visit Alan Paton, author of Cry, the Beloved Country, and with him produce a series of photos to illustrate an article for the magazine.

Clarke rapidly moves from here to presenting the work of Eli Weinberg, co-founder of the Garment Workers Union and Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) member. Weinberg photographed “a tenacious group of liberation activists” including Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Nelson Mandela and Ruth First.

This is not, however, just a story of white photographers. One of its outstanding characters is Alf Kumalo. Alf photographed Winnie Mandela, Steve Biko and the Soweto student uprising in 1976. Kumalo, along with many other great journalists, worked for the Drum magazine.

Throughout Clarke’s photographic history of struggle is inserted contextual writing telling the terrible story of the development of apartheid and its increasing repression. It is not possible in a brief review to do this justice, but chapter headings such as “Struggle Photography — Quiet Social Moments and Frontline Activism” give a clue to the power of this narrative.

The book rightly ends with photographs and stories from post-apartheid South Africa with documentary and art photography from Andrew Tshabangu, Lindokuhle Sobekwa and others.

Clarke could have taken the easy route of choosing well-known photographs to illustrate his story of the tragedies and joys of this beautiful country of South Africa and its people. However, he has succeeded instead in ensuring the narrative is closely represented in the images selected.

Clarke approaches the subject with a critical and historical lens, analysing photography as both an artistic expression and a socio-political tool. He examines how images have shaped narratives of identity, resistance and power in South Africa, blending visual analysis with historical context to reveal deeper meanings behind iconic photographs.

I would recommend this book highly to artists, photographers and anyone who has an interest in the political history of South Africa.