This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

The Scottish Colourists: Radical Perspectives

Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh

THIS is a very surprising and subversive show.

It presents itself as a celebration of “the Colourists” who are regularly held up as doyens of Scottish Modernism. These were JD Fergusson (1874-1961), SJ Peploe (1871-1935) and FCB Cadell (1883-1937), the upper-middle-class painters wealthy enough to visit pre WWI Paris and who adopted the high key palette of the French “Fauves” (the Wild Ones).

Previously they had painted posh still lives in muted colours — silver jugs, fans and jonquils — and after Paris they painted them again, but in thick blocks of primary colour, before retreating to Iona to render its empty beaches in ethereal pinks, blues and whites. So far, so familiar.

But this exhibition contextualises their work by showing what their contemporaries — Whistler, Sickert, Derain and others — were up to at the same time. They were frequently collected by the same person, the Scot, Alexander Reid, although not the English Roger Fry, and exhibited in the same galleries in London, notably Leicester Gallery.

This context delivers a number of shocks to their “assured” place in modern art.

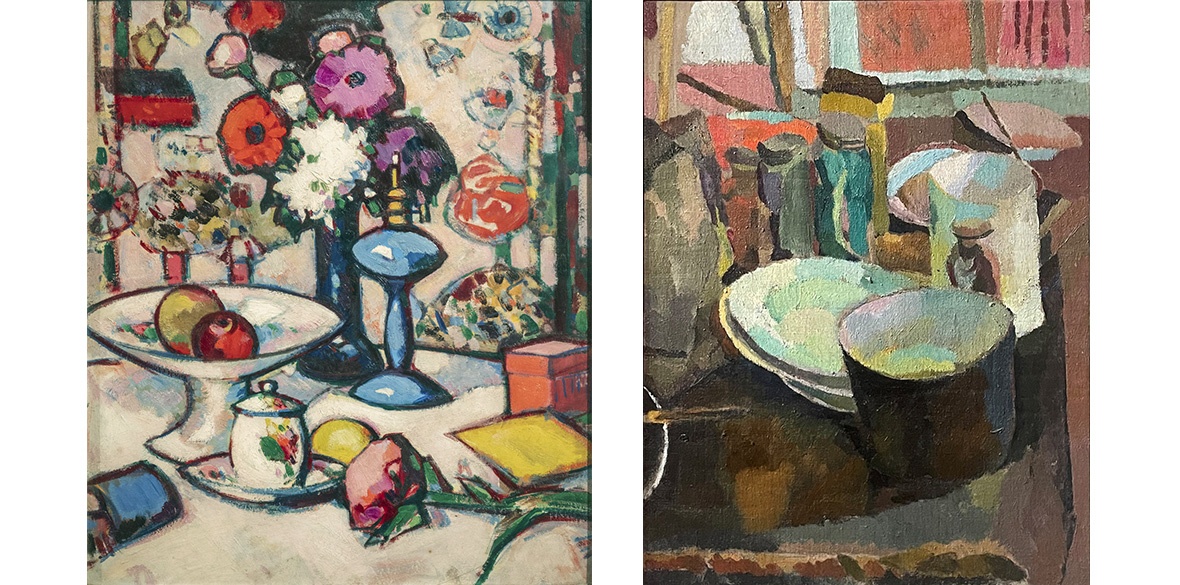

The first shock is to realise how limited the social vision of the Colourists was, and how divorced they were from the radical roots of French Realism. Neither Peploe, Fergusson nor Cadell ever step beyond their own social circle, nor include an everyday object in their compositions that doesn’t indicate entitlement and reflect their patrons’ tastes.

Van Gogh’s chair, pipe, boots and Potato Eaters this ain’t. Nor is it Cezanne’s overflowing bowls of fruit on a kitchen table. Instead, in “liberated” brushstrokes we get society beauties, elaborate hats and Georgian New Town interiors. They cling, even in circumstances of war and poverty, to their privilege.

The only working-class image in the show, Charles Gunner’s Old Sweeper of 1913, represents something that the Colourists were not, namely: born and educated in a French system (albeit to British parents) where non-academic art had been seized by a class determined to represent itself for the first time. The liberated petit bourgeois vision, Realism, rapidly became revolutionary — scornful, splashy, reductionist and joyful — and everything that unchanging academic competence wasn’t.

Clearly, it is one thing to be educated in those class truths, and quite another to visit it as tourists like the posh Scots.

Leslie Hunter (1877-1931), the US-raised adjunct to the group, didn’t share the wealthy Edinburgh background and training of the other three, and in his short, troubled life dashed off a number of small social scenes on the beach in Fife. But that’s it.

The next shock is to realise that the label “Colourist” is a brand aimed at a gullible public and art market, after their deaths. “Colourist” had been mooted as a characteristic of these “Modern Scottish Painters” in 1925 but wasn’t formally adopted as a descriptor for the group until 1951, by which time only Fergusson was still alive.

It wasn’t, in other words, the way they understood themselves. Rather Fergusson, the most manifesto-minded of the four, had defined them in 1911 as “Rhythmists” and edited and illustrated the journal Rhythm (1911-1913) to expose this idea.

To understand what the Rhythmist manifesto was it must be judged alongside those of their better known contemporaries, the Futurists, Vorticists, Surrealists, Cubists et al. Rhythmism is founded in Henri Bergson’s theory of Vitalism, “Elan Vital” or “vital life force.” It is an individualistic ideology, bereft of social conscience or engagement, that, unsurprisingly, was adopted by fascism.

The term “Colourist” is a later and neutral disguise for this elitist practise, rebranding the work as apolitical and purely aesthetic, and deployed ever since for the benefit of a small coterie of Scottish art dealers to grow rich through tactical marketing and sales in Scotland.

Colourism never was a living movement and is anything but inspiring, petering out as it did in the bland tourist-board posters which Cadell produced for the MacBrayne ferry company, and the vacant holiday scenes with which they concluded their careers.

And the third shock is that the enduring images that resonate in today’s Scotland have nothing to do with being “Colourist” at all.

Throughout the show, from first to last, are threaded works by the Scottish-born non-Colourist but also non-stop contemporary, Duncan Grant (1885-1978), and his work subverts the socially blinkered vision of the Scots every step of the way.

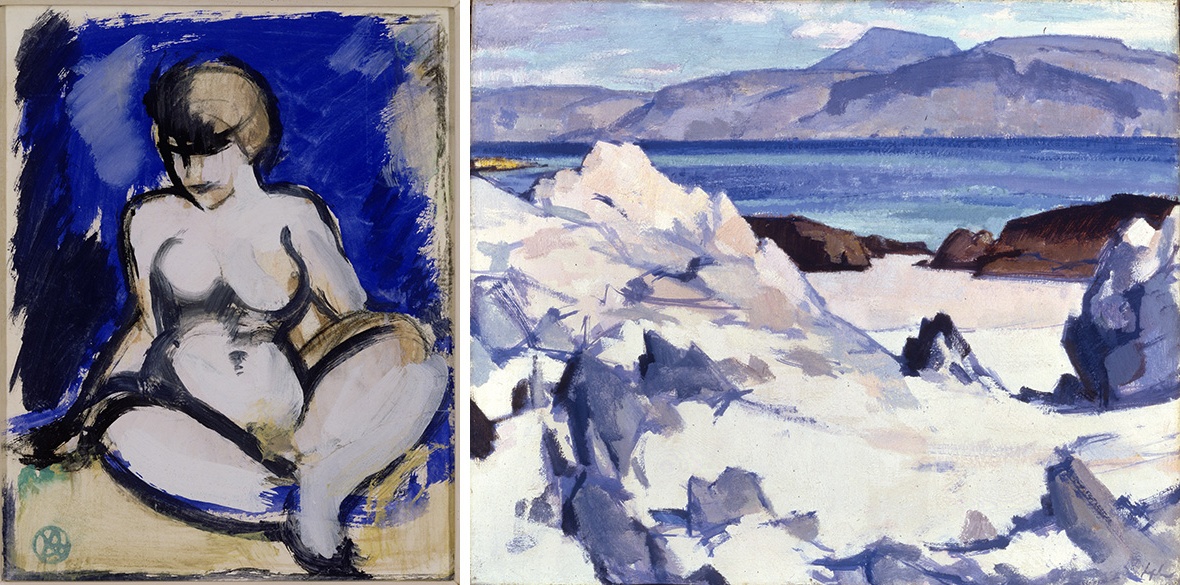

At the start, twinned with the social mask presented by Fergusson’s portrait of Jean Machonachie (1902), is Grant’s naked Self Portrait In A Turban (1910), the very opposite of a declaration of social status. Although it is not displayed here, Grant’s well-known Bathing (1911) is a more convincing study of rhythm and stylised movement than anything Fergusson came up with. And beside Fergusson and Peploe’s interchangeable post-war block-colour still lives we find Grant’s altogether more humble, more modern, and more moving Still Life With Dishes, Jars And A Bowl (1918) that anticipates the coming abstraction of Morandi and Ben Nicholson as the others cannot.

So, the radical perspectives of the show’s title are not what you expect. Rather, the surprise is the revelation that these were highly conservative appropriators of style, better achieved elsewhere, and that, in the end, it is not their colourism but their conservatism that unites them.

That is, until you come to Cadell’s Portrait Of A Boxer (1924). This remarkable painting points elsewhere. Cadell portrays this working-class man because he admires and desires his body. The boxer’s handsome face shifts and blurs — it is a study in evasion — and directly behind it looms an ogre, fiercely angry and dark, that could be the Marquess of Queensbury himself, Britain’s pin-up homophobe.

The boxer’s body is strikingly similar to the one depicted in Bather In A White Hat (1920s), the portrait Cadell made of his post-war man-servant and lover Charles Oliver. Here, that same naked male body is positioned in allegorical space, on the symbolic “Red Chair” that Cadell first used to depict the absence of his pre-war class equal and lover Ivor Campbell, whose death in the trenches was the trauma that dominated Cadell’s life.

He first painted the chair as empty, and then reserved it for Campbell’s substitutes. These were the tenderly depicted model for Negro In White and Pensive Negro, both remarkable portraits that attempt with partial success to negotiate racism and imperialism, and then William “Basher Willie” Thomson, the subject of the painting in question, which is less a formal portrait than an eloquent depiction of the psychological reality of internalised homophobia.

This work lifts Cadell away from the Colourists altogether and into the company of another pioneer of British modernism, Glyn Philpot, his direct contemporary. Also, and similarly to Philpot, it anticipates in line, colour and subject the later pop artists, like David Hockney or Peter Blake, who explore homosexual desire openly, and legally, even if they lack the facility to express the oppression that comes with it in the same way.

It is in this, and this alone, that just one of these artists maintains relevance in today’s Scotland. Only in this minority avenue do the revolutions on which the “Colourists” hitched a ride continue to signpost the freedoms still to be won.

Runs until June 28. For more information see: dovecotstudios.com