This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

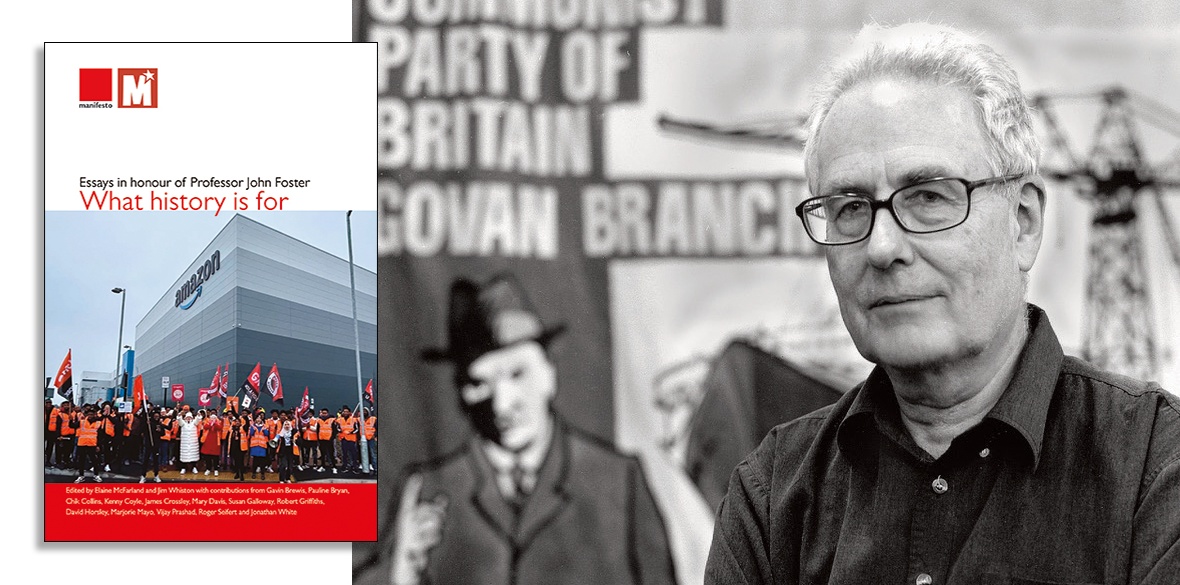

What history is for: Essays in Honour of Professor John Foster

Ed Elaine McFarland and Jim Whiston, Manifesto, £12.50

JOHN FOSTER’s response to the title of this slim volume of a dozen essays which focus on his lifetime’s work over the last six decades might well be “praxis,” the Marxist term denoting that neither theory nor practice are intelligible in isolation from each other, but need to be tested by material reality.

Unlike Hegel’s Idealism and rhetorical abstraction against which Marx & Engels unleashed “historical materialism” as a guide for the class conscious working-class struggle to replace the ruling class by the proletariat using its collective power and agency, dialectically, to create itself as a unified class for, and against, all others.

Unlike his older fellow Marxist historians, Eric Hobsbawm and EP Thompson, Foster has kept these insights alive by nailing himself since the 1960s to the Communist Party and the organised broad left movement based in Scotland as political activist, leader, strategist, intellectual, spokesperson, organiser, archivist and defender of the Morning Star and its readership. Indeed, the Morning Star only survived the 1980s through people like Foster, Mary Davis and Robert Griffiths.

Hobsbawm and Thompson, whose ground-breaking Marxist histories focused on the 19th century working class — Labouring Men (1964), Industry and Empire (1968), The Making of the English Working Class (1963) — were emulated by the young Foster in his Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution (1974), but while they were becoming celebrated public intellectuals, Foster and his colleague Charles Woolfson at Strathclyde University were writing definitive accounts of The Politics of the UCS Work-In (1986) and Track Record: the Caterpillar Occupation (1988), subjects one can hardly imagine being tackled knowledgeably either by Hobsbawm or Thompson.

Indeed Hobsbawm penned the speculative treatise The Forward March of Labour Halted (1981) despite being neither an active member of the CPGB or an authority on modern trade unionism, which enabled the Eurocom clique around Marxism Today to attack the alleged “economism” of trade unions and their leaders, strengthening Neil Kinnock and Jimmy Reid — writing for Murdoch’s Sun — in their combined onslaught against the 1984-5 miners’ strike, leaving the Morning Star and its broad-left readership to carry on the fight against Thatcher and the mainstream media all on their own.

So of course this collection of essays must be read by every Morning Star reader and labour and cultural activist in Britain and internationally.

The topics covered include Foster’s role as Scottish secretary and international secretary of the CPB, and overviews of his major books on the historiography of class formation and class struggle.

These include the huge impact that Thatcher/austerity had through deindustrialisation policies especially on poverty and health in the west of Scotland; workplace and community-based class struggles and conflict; the Red Paper on Scotland which traces Scottish capitalism and anti-capitalist resistance; strike waves and class struggle/consciousness in 2022-23; today’s hyper-imperialism; religion and English radicalism; black communists in Britain since Rajani Palme Dutt and Shapurji Saklatvala; and Engels’ concept of “social murder” as systemic violence “normalised” by capitalism through the chronic exploitation of workers, cuts to vital services and constant wars engineered for profit, resulting in the premature deaths of the proletariat.

These essays are written by a vast range of academics and socialist activists, many taught by Foster or whom he met through STUC committees, Scottish government working groups and labour and trade union settings.

Foster’s central role in organising talks on Our Class: Our Culture is missing but can still be glimpsed on YouTube with Dick Gaughan discussing, for example, the need for the trade unions to financially support/offer patronage to radical artists and poets by giving them gigs at conferences, strikes, demos — a still unrealised potential.

Foster’s most recent book Languages of Class Struggle, also extends his work in the direction of cultural materialism, and examines five significant working-class mobilisations which required state intervention, observed also through the perspective of “intertextuality” and “materialist dialectics.” These are the General Strike of 1842 and Karl Marx; Councils of Action in Britain 1920; Belfast Strike/Ulster State 1919-20; Clydeside and Britain 1919; Clydeside and Britain (UCS Work-In) 1971-2.

These events are analysed in historical materialist fashion by identifying the splits between large capitalist owners and small local capitalists, and the similar problem of keeping the workers’ side united. Both sides sought to shape and control the emerging narrative with constant interventions from the media.

This was a central feature of Foster and Charles Woolfson’s UCS Work-In study (1986), but this new book draws on further work by Woolfson and Chick Collins on Marxist theories of language — specifically the more recently translated “materialist dialectics” of Soviet linguists like Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and the Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkove (1924-70) — which serves, in Foster’s words, to “restore the stress laid by Engels and Marx on the material context of revolutionary mobilisation and its consequences for thought and language.”

Foster’s brilliance as a Marxist intellectual is everywhere acknowledged, including by mainstream social democratic historians he has debated in print — Robert Gray over “the aristocracy of labour,” Ian MacLean over the redness of “Red Clyde” — and any number of socialist and social democratic apologists for Scottish nationalism against whom Foster has argued.

In the latter case he helped to refine the CPB/STUC’s 60-year-old case for “progressive federalism” which neither Alex Salmond nor Gordon Brown allowed into the 2014 Scottish referendum options, because it would have democratised the British state entirely as Pauline Bryan argues forcefully in her essay on the Red Paper.

Intellect aside, Foster is never happier or more relaxed than when among the activist foot-soldiers of the broad left — on demos, workshops, talks, discussions — with autodidacts like Keith Stoddart in Glasgow and Richard Shillcock in Edinburgh, comrades who, like him, have stayed the course. They are the people whom Foster writes history for, and the broad left readership of the Morning Star.

As cultural materialist proof I offer a poem in memory of Foster’s old comrade, Eric Atkinson, CPGB party organiser for West Lothian as well as finance secretary for the Scottish District. Atkinson was a man of huge acumen who called everybody “comrade,” especially those who patently were not, but whom he hoped to win over through discussion, managing, with Thatcher’s Falkland’s war, to coax me into the party in spring 1982.

The why is in the poem.

See here for more podcasts from Manifesto press.