This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

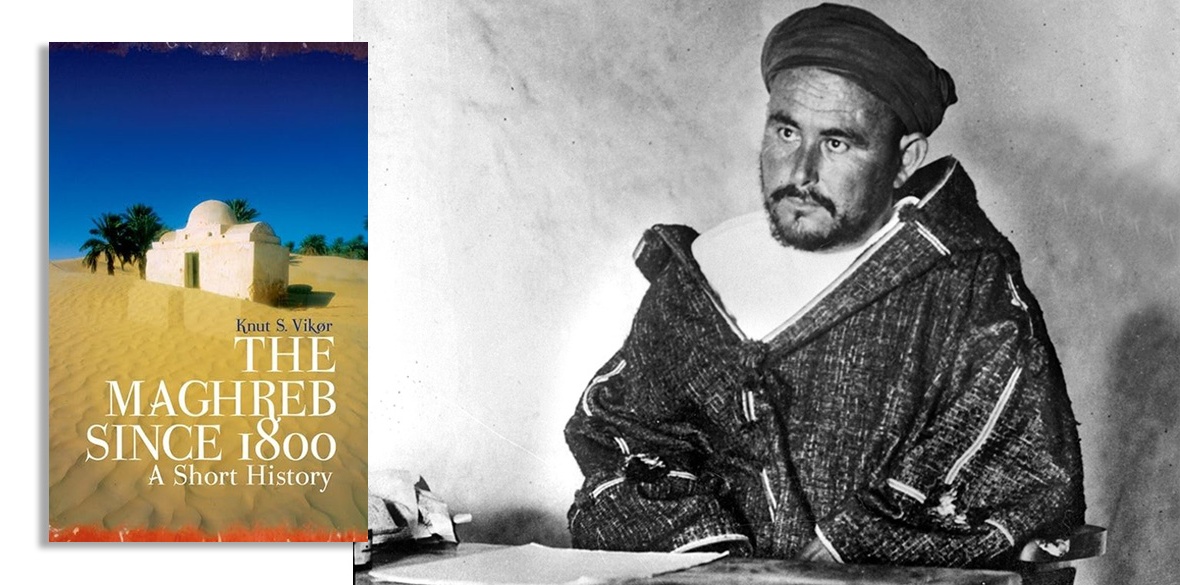

The Maghreb Since 1800: A Short History

Knut S Vikor, Hurst, £19.99

AS AUTHOR Knut S Vikor says in his introduction, the term “Middle East” was a British colonial invention, covering the region controlled by the British empire from Egypt to Iraq and the Arab Gulf.

The Arabic names for the region that became united under the Islamic Caliphate are much older: it was divided into the Maghreb (where the sun sets) to the west, and the Mashriq (where the sun rises) to the east. The Maghreb extends from the Western Sahara and Morocco in the west to Libya’s eastern border with Egypt in the east.

The present-day division between the southern Mediterranean and its northern shores — the fortress Europe where thousands die each year trying to reach Spain or Italy — came about half a millennium ago when the Spanish crown expelled Muslims and Jews in 1492, and the Ottomans gradually extended their hold on north Africa westward to Tunis and Algiers.

In the west, one of the world’s oldest dynasties, the Alawis, took power in Morocco in the late 17th century and remain the ruling family until today, surviving the period of French direct rule in the early 20th century.

Knut’s book roughly covers the period of European colonialism in north Africa that began with the French conquest of Algeria in 1830.

He divides the region according to the form that colonialism took, with Morocco and Tunisia ruled with the assistance of local elites, while Algeria and Libya experienced a more violent and thoroughgoing form of settler colonialism that ruthlessly suppressed resistance.

In Morocco, there was also resistance to the push by French and Spanish forces to conquer and divide the country between them, with a rising in the Rif region that led to one of the most spectacular defeats of European colonialism in 1921, when a 13,000-strong Spanish army was obliterated by the Rif forces, leading to the short-lived Rif republic.

Disappointingly, this little-known catastrophe of colonial history is passed over in Vikor’s book without a mention of Spain’s shocking defeat, which led to the abdication of King Alfonso XIII.

Vikor does make up for a certain lack of texture and detail with commendable balance and clear historical narratives, exposing the injustices of colonialism and the complexities of local and regional politics, as rival leaders and dynasties negotiated and fought for control.

He describes how the French, and later Italians, supplanted the Ottomans in Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, drawing a clear line between the settler regimes that were imposed first in Algiers and then in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, and French rule in Morocco and Tunisia.

While the Ottomans had taxed the locals who owned the land, the French seized vast swathes of land from them, with 18 million hectares in Algeria transferred to European owners.

The conquest of Libya began in the early 20th century, where Italian forces struggled to impose control. Still, after Mussolini seized power in Rome, the fascists began a war of conquest with the notorious general Graziani brutally executing thousands of the Senussi tribe, and forcing the population into concentration camps in 1930. The execution of Cyrenaica rebel leader Mukhtar in 1931 marked the end of the resistance.

While 100,000 Italian settlers populated the colony, it was short-lived, with the fascists defeated by the British at Tobruk in 1942. Libya won formal independence in 1949, under King Idris, who became unpopular for his pro-Western policies and was later overthrown by junior army officer Muammar Gadaffi.

The struggle for Algerian independence was bloodier than it was for the other Maghreb states and lasted until 1962. In Algeria and Libya, the military was the only cohesive national institution where colonialism had shattered the social forces that could have helped unite the two vast and disparate territories.

The author gives a fair hearing to the experiments in “Islamic socialism” in both Libya and Algeria, both supported by state oil revenues. The latter was hit by falling oil prices in the late ’80s, which opened the way to elections and the victory of the Islamists, sparking a coup and decade-long civil war.

Gadaffi had to curtail his broader goals of pan-Arabism and then pan-Africanism, seeking a short-lived accommodation with the West after 2003.

The book takes us all the way up to the uprisings of 2011, which saw the dictator in Tunisia, Ben Ali, flee the country, sparking a region-wide upheaval, and the Nato-backed war that overthrew Gadaffi. Libya remains a failed state, while Tunisia returned to one-man rule under Kais Saied.

It ends with the unresolved tensions between Morocco and Algeria over the Polisario struggle for independence in Western Sahara, where Rabat seized control from Spain in 1975 and has failed to abide by UN resolutions ever since.