This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Letizia Battaglia: Life, Love and Death in Sicily

Photographers’ Gallery, London

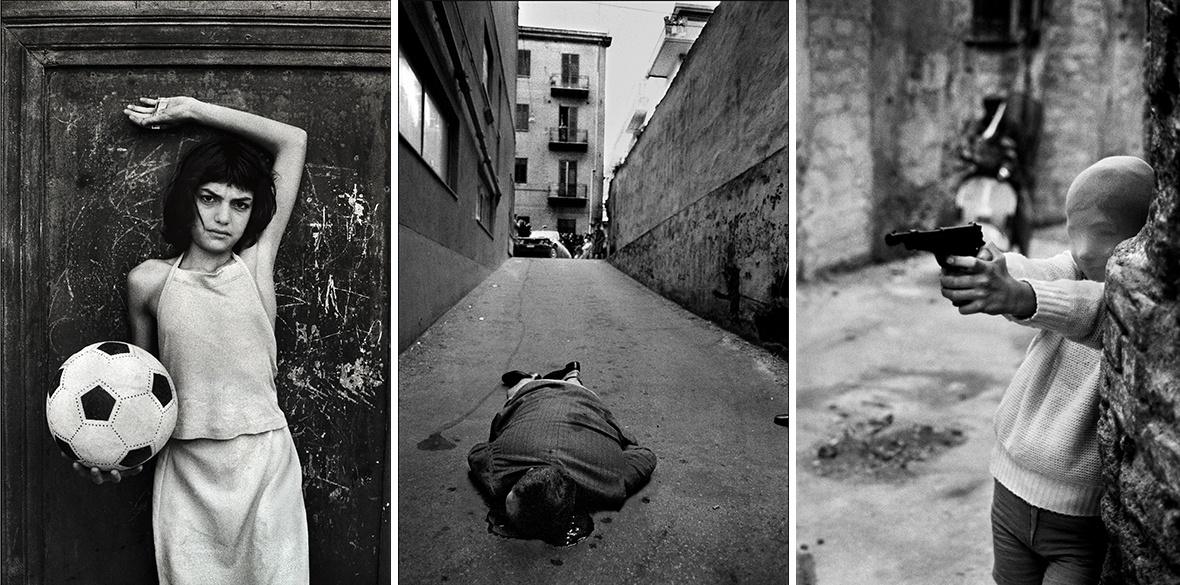

WHEN we look at pictures of conflict, violence and collective trauma we might expect to see only the horrors of maimed bodies and the crying souls of the victims. But in the photographs of one of Italy’s most cherished photographers, Letizia Battaglia, you do not see glamorised shots of the perpetrators because her images aren’t about them. They are about places and people.

The horror is there, but you also see flowers, a football, engaged crowds, and children in the street. Sure enough, some of these children hold guns because her pictures capture the normality that exists around the brutal violence in daily life.

Letizia Battaglia was born in Palermo, Sicily, in 1935 and was among the first women reporters in Italy. She died in 2022. She travelled the world with her pictures and won several awards for her photo-journalism.

Her work is testament to a ferocious love of Sicily, a love that went beyond the camera and later took her into political office as a green party candidate, to seek justice and peace for the normal people whose stories she told with her images.

This exhibition is the first major exhibition in Britain and shows work from the 1970s-1990s. This was the golden age of Cosa Nostra, when the criminal organisation was conquering space in the global heroin trade while maintaining a firm grip on local and regional contracts. Battaglia captured all facets of life around the mafia in this period, from moments of violence and despair to melancholy and even joy.

Since the mid 1970s, Battaglia was the photography director of L’Ora, Palermo’s left-wing daily newspaper. L’Ora signalled the birth of public anti-mafia sentiments in Sicily and in Italy.

She or one of her assistants would go to the scene of every major crime in Palermo until shortly before the paper shut down in 1990. Through her lens, Battaglia put on display the complicated reality of the mafia in Sicily in stark black and white.

On the one hand, the poverty and the misery of certain areas of Palermo that echo the brutality of Cosa Nostra. On the other hand, the Sicilian way of life, of festivals, feelings, spices, religion and simplicity, that seemed to co-exist with the mafia. We now know how this complex relationship with a city and its people is key for mafia organisations’ success, in Italy and abroad.

Letizia Battaglia’s photographs were revolutionary as they stripped the mafia of its glamour by showing not only its violence – the murders and the desperation it created – but also the banality and the normalisation of it all.

The Palermo that we see through Battaglia’s eyes is a city in the midst of mafia killings but children are still running around and parents are still going to church. From the 1970s to 1990s, Cosa Nostra’s internal instability and quest for power made countless victims – sometimes two a week in the most violent periods.

Mafias need “order” to boost their profit and their power. Order means getting rid of enemies and people who speak too much. Crucially, not all their victims were mafiosi. Among the hundreds killed were entrepreneurs, members of the church, law enforcement, doctors, lawyers, journalists and politicians.

One particularly important photo on display is of the assassination of Piersanti Mattarella, the president of the Sicilian region at the time and older brother of Sergio Mattarella, who has been President of Italy since 2015. Battaglia was one of the first on the scene to capture Mattarella dead in his car after being shot in front of his wife and daughter. The case of Mattarella’s murder is still open and remains one Italy’s unsolved crimes. The latest updates on his murder came only a few weeks ago in 2025.

Cosa Nostra also killed children and women. Battaglia –– like other L’Ora journalists –– was repeatedly threatened. The exhibition includes one incredibly intimidating letter she received from the mafia asking her to stop photographing their victims.

She did not shy away, however, and bravely showed how Cosa Nostra was manipulating the culture of Palermo and Sicily. People valued honour and respect but Cosa Nostra used those same values to justify itself as an “honourable society” in spite of its dishonourable actions. This manipulation of their core value system was so deep that Sicilians were forced to normalise the mafia’s revenge and extreme violence in the name of a distorted version of “honour.”

In Battaglia’s photos no character is presented as more important than the others. Every bit of Palermo becomes the protagonist of its own shot. For example, the little girl with icy black eyes, whom Battaglia photographed in 1980 holding a football against a wooden door, looking like she is about to spit life out. That photo is as powerful as the one of Judge Giovanni Falcone at the funeral of General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa who was killed by Cosa Nostra in 1982. Falcone would be killed by Cosa Nostra ten years later.

At the same time as the exhibition in London, another is showing Battaglia’s photos in Calabria, Italy. In this exhibition, her photos are displayed outside on a long avenue in Reggio Calabria that overlooks the Mediterranean sea and Sicily. This exhibition carries a title that carries a promise: “Endless” (Senza Fine).

Endless as the silent revolution of Battaglia’s photos, for Sicily, for Italy, and for the anti-mafia movement.

Runs until February 23. For more information see: thephotographersgallery.org.uk

Anna Sergi is Professor in Criminology, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

![]()