This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Toby stood outside the terraced house with the red door, cradling the stone against his chest.

Jack and Ollie had egged him on all the way from school, clapping him on the back and whooping.

“Go on,” Jack said.

Toby hefted the stone from one hand to the other, trying not to look as though he was stalling. It was not so much a stone as a lump of brick and mortar he’d found on the demolition site of the old library, but it would do. He closed his eyes to imagine it hurtling through the air and cracking the window.

“What are you waiting for?” Jack urged. “Are you chicken?” He started dancing round Toby making buk buk noises and flapping his arms.

Ollie joined in. “Go on. Throw it. If you wait any longer the chavs from the estate will come and pick a fight.”

Toby was one of the kids from the estate. At least he had been until he and his mam moved in with his nan after Dad died. But if he told Ollie and Jack where he came from, they would stop letting him tag along. They were the only mates he had made since he moved schools. Not mates exactly, but they talked to him. The others all looked at him like he was dirt. He hefted the stone to his shoulder, then swung his arm back to get some power behind the throw. As though he was playing cricket in the park and not about to smash his teacher’s window.

As the door opened, the sound of pelting feet echoed behind him. Not daring to look round, he knew he was alone.

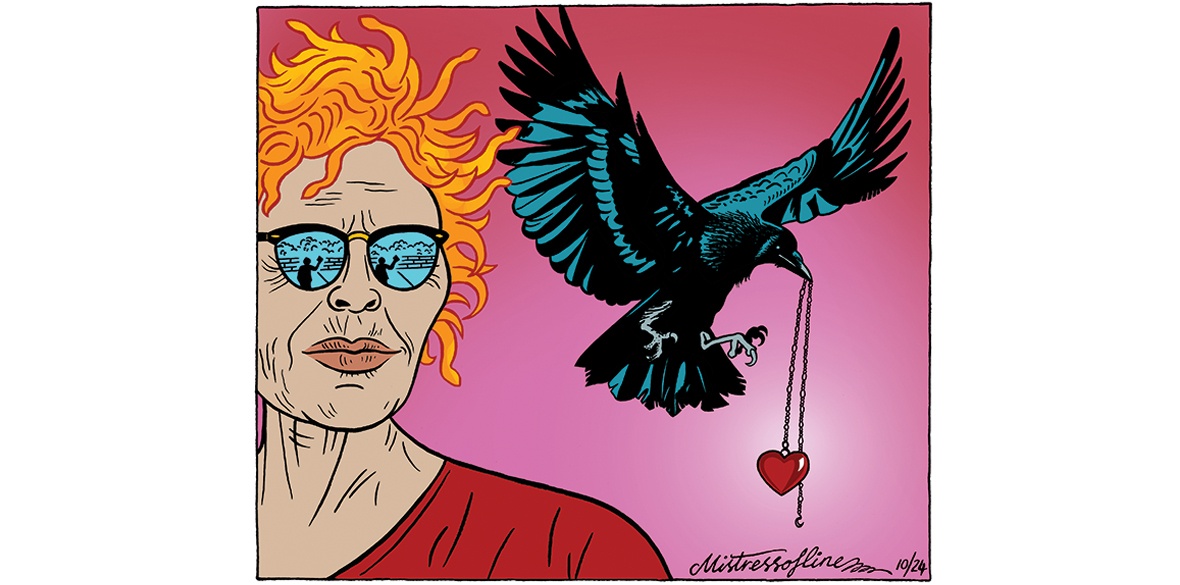

The lamia in the doorway smiled, fangs bared. “Hello, Toby.” Copper snakes writhed about her head and the late afternoon sun dazzled him, reflected from her mirrored sunglasses.

“Miss Lyra.” He pulled in his arm and rested the stone against his shoulder, trying to look as though he was passing by and not about to smash her window. He kept his gaze on the blue and grey zig-zag pattern of her robe; he could not look her in the face.

“Come in,” she said. “Kettle’s on. Let’s talk about why you want to throw stones at my window.”

Toby stayed put.

“Let’s go,” she repeated, and he glanced up. Her smile held but there was steel in her jawline.

Toby tried not to show his fear. Her snakes could fill his veins with venom if she chose. The weight of the stone in his hand reminded him of his purpose. It would be so easy to throw it and run. He tightened his fingers around it, rubbing his thumb across the rough surface.

Jack’s voice repeated in his head.

“Dad says, you could leave a job on a Friday and have a new one Monday.”

“Dad says, you could leave your door unlocked while you went to the shop.”

“Dad says you could say what you liked without wokies getting offended.”

The part left unsaid was always, “Before they came.” Jack and Ollie would be pleased if he threw the brick and ran. He followed Miss Lyra into her house instead. He was not sure why.

Inside, blue and silver cushions lined the floor along one wall. In the middle of the room, on top of a soft rug the colour of a stormy sea, stood a low table with a basket of pomegranates.

“Take off your shoes,” Miss Lyra said, and Toby left them next to the door. She moved into the kitchen, the scaled lower part of her body gliding across the tiled floor. Toby hoped she wouldn’t notice his socks had holes and didn’t match.

A cage sat on one of the kitchen worktops with a crow inside. The bird watched him with keen black eyes through the bars, its head cocked to one side.

“You’re not supposed to keep crows, Miss. Are you going to eat him?”

Miss Lyra’s snakes all hissed at once. “What do you take me for?” she said.

Toby shrugged. “They say you...”

“They say I what? Eat birds? Babies? People’s pets?”

Toby hung his head. That was exactly what Jack and Ollie said.

“His wing was injured by the neighbour’s cat. I’ve been looking after him until he can fly again.” Miss Lyra placed tea bags in two mugs and poured in boiling water from the kettle. “I’m letting him go today. You can watch if you like. Sugar?”

Toby shook his head.

“Milk?”

“Yes please, Miss.”

When she was done, she handed him a cup of tea. It was nice and strong. Builders’ tea, his dad would call it. He took a sip and savoured the taste.

Miss Lyra put down her cup and slid over to the bird cage, softly hissing words Toby could not understand. When she opened up the door and put her hand inside, the crow hopped onto her finger as though he had been tame his whole life. He clung there as she carried him to the back door and opened it wide. She brought the crow to her face and kissed the top of his head, before murmuring some more words that Toby did not understand. Jack would say that she should speak English, but Toby liked the lilt in her voice when she spoke her own language.

The crow flew away.

Toby took another sip of his tea as she closed the door.

“Now,” she said, her copper-coloured snakes all watching him. She tapped the nail of her index finger against the granite countertop. “You have partaken of my hospitality, and so you may never lie to me in my home.”

Toby almost laughed, but the hiss of the snakes stopped him.

“Why were you going to throw that stone through my window?”

He said, “Because your kind don’t belong here.”

At least, that was what he meant to say, what Jack and Ollie kept telling him. What he heard, what came out of his mouth, was, “I’m ashamed because I can’t read, and I miss my dad.”

He dropped the stone in his haste to clap his hand over his mouth.

“What did you do to me?” he meant to say.

“My mam works two jobs and we still need to use the food bank,” was what he heard.

A tear ran down his cheek and he scrubbed it away and picked up the stone. Part of him, the part where the tear escaped from, wanted to throw it at her anyway, for making him feel what he had so carefully hidden behind bravado and scorn to fit in with people like Jack and Ollie.

“Drink your tea, Toby,” Miss Lyra said. “And put that stone where it belongs.” She pointed to a tall pedal-bin by the back door.

Toby looked down at the stone in his hand. A grubby, mean thing, it sat there, heavy with all the anger and fear inside him. He crossed the room and pressed the pedal. When the lid came up, he held out his hand, then pulled it back.

The bin was full of stones.

“What’s this supposed to be?” he said, and for once the right words came.

She smiled then. “Let it go, Toby. Don’t let them divide us.”

He dropped the stone into the bin and let the lid fall. He didn’t feel any different.

“What now?”

Miss Lyra held out a book. It was one of those they gave to first-year kids like his sister.

He opened his mouth to tell her where to shove it but was afraid of what might come out instead.

“No-one needs to know,” she said. “You can come after class on Wednesdays; I’ll help you catch up.”

He shook his head. “They’d bray me if they saw me coming here.”

“Then let’s do it at school. Tell them it’s a detention.”

“Thanks, Miss, but it’s no use. You’re not the first one to try. I’m too thick to learn, everyone says.”

She cocked her head like the crow, her expression unfathomable behind the mirrored glasses. “Then why not prove them wrong?”

He finished his tea and handed her the mug.

“Thank you, Miss. Can I go?”

“Of course.”

Later, when Ollie and Jack came round to find out what happened, he told them Miss Lyra had given him a detention, though he was still not sure he would go.

“What a witch.” Ollie picked up the kid’s book Miss Lyra had sent Toby home with. “What’s this, borrowing your little sister’s books now?”

“Alice must have left it in here,” Toby said.

“You’re not going to go the detention, are you?” Jack said. “You didn’t do anything. We don’t take orders from snakes.”

“Of course not,” was what he meant to say, to get them off his back. What he said, was, “You shouldn’t talk about Miss Lyra like that. She’s lovely.”

After they were done beating him, Toby went back to her house.

“Please.” He wept. “Take your spell off me. I can’t fit in any more.”

Miss Lyra shook her head. “There is no spell. Whatever you said was in your heart.”

“But …” What was he supposed to do? He couldn’t go around saying things like that. They would make his life a misery.

She wiped a tear from his cheek with her thumb. “Letting go of the hate is only the first step, but once you take it there’s no turning back.”

“I’m afraid,” he said.

Miss Lyra smiled. “We all are.”

Cheryl Sonnier grew up on a council estate in South Yorkshire and, after much moving around, now lives on a council estate in Leeds. Cherylsonnier.com

Stories, of up to 1,600 words, should be submitted to: morningstarshortstories@gmail.com