This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1

By Karl Marx, translated by Paul Reitter, Princeton University Press, £35

The first English translation in 50 years of Karl Marx’s Capital Volume 1 was published several months ago by Princeton University Press. Translated by Paul Reitter, this version is the only one based on the last German edition revised by Marx himself.

Reitter, in his Translator’s Preface, suggests that previous translations had difficulties in consistently handling Marx’s neologisms, held limiting policies such as noun-to-noun translation, fell short in rhythm and cadence, missed a certain sarcasm, and failed in “preserving the vividness and resonant qualities of the language in Capital.”

The upshot is a more readable, relatable, and refreshed Capital, that is more conversational, with Marx’s own style visible. In a thoroughgoing analysis of production, money, the commodity form, surplus-value, machinery, wages, accumulation, colonisation, and so forth, Marx historises, contextualises, and uncovers exploitative aspects of political economy that bourgeois economists had concealed, naturalised, and presented as inevitable.

Paul North’s Editor’s Introduction draws on the latest scholarship. He suggests that the motivation for the monumental task of Capital was Marx’s indignation and anger. This had been focused variously on the Prussian government, philistines, reformers, philosophers, Hegel, followers of Hegel, liberals and most other socialists but finally finds itself at home with the grand target of the entire capitalist system. Anger becomes prose, persistence, principle, tone, cynicism, and style.

The motto for Marx’s anger emerges: “Theory becomes a material force. Critique as a weapon that grips the masses.” The basic outrageous fact that Marx underscores is “that workers are complicit in a system that does not benefit them, and everyone is complicit in a system that benefits no-one in the long run.”

The introduction raises key concepts and admits this is a notoriously difficult and foreboding text, at times anachronistic, relying on acquaintances the modern reader lacks. Therefore, the introductory overview offers a helpful schemata and guidance for engaging with Capital.

Wendy Brown in the foreword proposes that “understanding capitalism means grasping all of its conditions, requirements, drives, mechanisms, dynamics, contradictions, crises, iterations, and above all its world-making and world-destroying capacities, its life and death drives.”

Capitalism’s ambition is to extract, extort, exploit, commodify, and monetise every possible entity. Be it from anticipatory colonisation of the planet Mars to the attention economy of the smallest pixel, or from century-long contracts to the quantified nano-second of the contemporary worker. Capital touches every living being and fossilised element on Earth and beyond. Even fictious phenomena are not immune: speculative markets and financialisation see to that. Needless to say, in attempting the critical analysis of all this, “Marx’s task was enormous.”

The core revelation of Capital, for Brown, is that “capital is the coagulated effect of the labour it exploits.” This is exemplified in Marx’s gothic turn of phrase: “Capital is dead labour that acts like a vampire: it comes to life when it drinks living labour, and the more living labour it drinks, the more it comes to life.” In this horror show the masses are impoverished and wealth is concentrated among the elite.

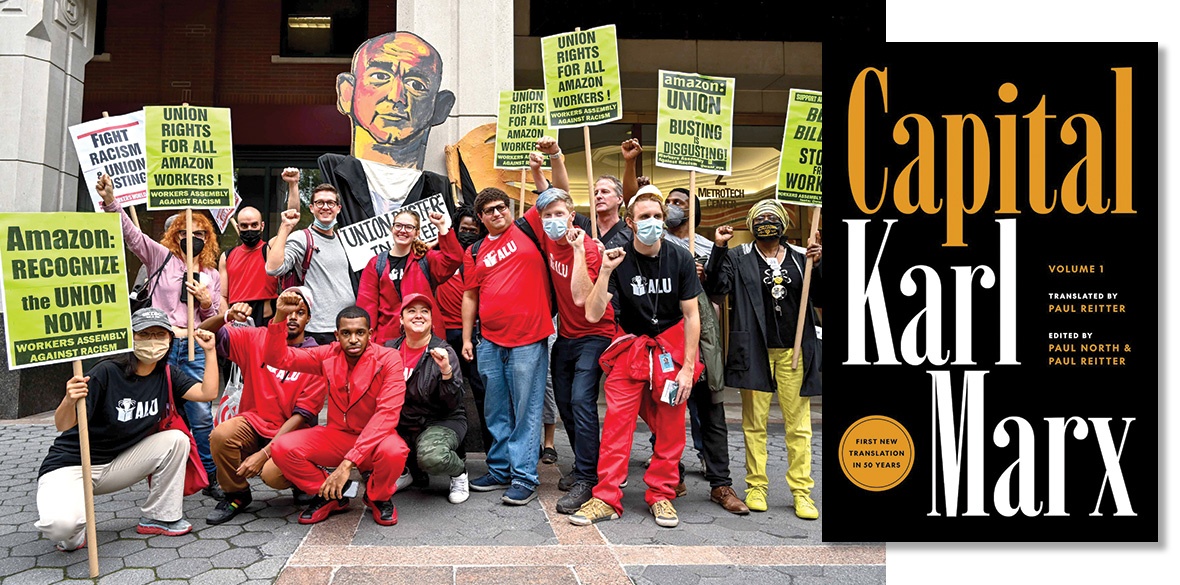

The antagonism between exploiter and oppressed has been continually buffered and mediated by social democracy, the social state, the middle and professional class, identity politics, populisms, variants of fascism, neoliberalism, and minor concession, but the antipathy remains. Whether bushels of wheat or digital platforms, prison panopticons or surveillance-capital, mills and factories or Amazon warehouses and sweatshops, clipped coinage or cryptocurrency, the content changes and capitalism mutates but the necessity of critique continues.

One of the more pernicious aspects of capitalism is separation and division: workers from the means of production, workers alienated from their products, workers in competition with each other, regulation of private property, enclosure movements, and operations of reification and fetishism. As ever, what is needed is organised resistance from united labour, solidarity, subsequent redistribution, and clear-sighted critical analysis.

As the editor puts it. “Capital is still the best place to begin if you want to understand the societal and economic system in which most of the world now lives.”