This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

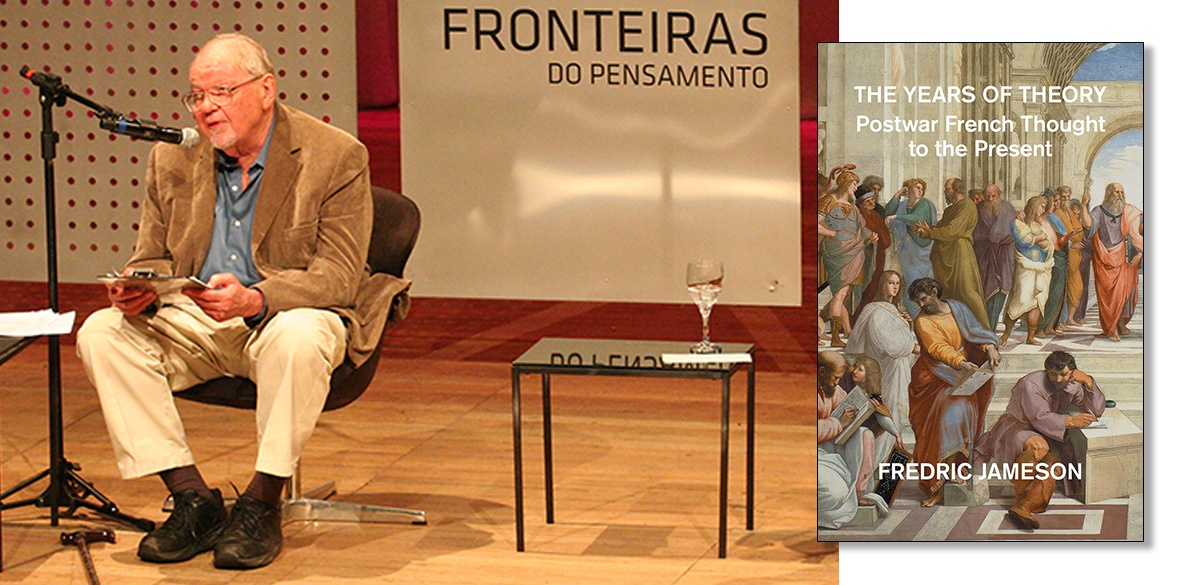

The Years of Theory: Postwar French Thought to the Present

Fredric Jameson, Verso, £20

THE great cultural theorist Fredric Jameson died in September last year aged 90. He was perhaps the most well-read person in the world. Concerning philosophy, anthropology, linguistics, cultural theory and Marxist dialectics, his range of knowledge was extraordinary. In The Years of Theory, his last book, what is also apparent is his masterful ability to convey ideas to students, to teach.

The Years of Theory is the transcript of a 2021 seminar on postwar French thought that Jameson gave remotely to graduate students during the Covid-19 pandemic. Interspersing his analyses of the great theoretical movements with personal biography and occasional fragments of gossip makes the abstractions he explores more vivid.

With an apparent sense of the generation gap, and of differences in attention span between today’s young reader and former ones, Jameson skilfully lures his audience towards the ideas by showing their emergence from real and challenging circumstances: Althusser’s psychotic episodes and eventual murder of his wife; Derrida’s loyalty in visiting him in prison; Sartre’s squint, repellent appearance and eventual blindness are examples. The outcome is a masterful exploration of the major figures of French theory which is both stimulating and accessible. This brilliant book is a page turner – I loved it.

Beginning with Sartre, subject of Jameson’s first book, published in 1961, the complexities of existentialism are patiently untangled. As someone who read all the Sartre and Beauvoir novels as a teenager, never fully grasping what was going on, many “now I get it” exclamations interspersed my reading of this chapter.

From keystones of German philosophy – Kant, Hegel, Heidegger – Jameson shows Sartre evolving his conception of existential freedom through the circumstances of 1940s Nazi occupation and onwards, towards the revolutionary change erupting on the streets of Paris in May 1968.

The book is an intellectual history packing in complex thought from structuralism through poststructuralism to what is shaping up as the posthuman age. Each chapter/session covers a theme taking 20 pages or so, the length of a seminar. Considering Jameson was 87 at this time of global pandemic, the sense of bringing a completed period to a close gives a late stage poignancy to his words.

Time is considered through the breaks in historical/materialist development. Breaks that are crucial to the paradigm shifts in ideas, and vice versa. Jameson’s structure shows the connections holding these dualities in relationship with each other. As the editor’s preface notes, French theory as a coherent conception of a certain period, a golden age so called, emerges in connection to “something much larger and more difficult to grasp – namely, the expansion of capitalist relations to a scale... unprecedented.” So, the book is a crucial evaluation of intellectual development through historical shifts which are now pressurising the whole of human life on Earth.

Inevitably “stuff” – a favourite term of Jameson’s – loses depth and detail in summary. What the book delivers instead is a sense of the whole, though visited in short stopovers, a bit of high-end intellectual tourism, offering a completed view of the period – the whole package – from which to engage with further journeyings.

With the Sartrean notion of freedom within the situation – “the writer is in a situation with his epoch” (Sartre), the book touches down in structuralism, taking in anthropologist Levi Strauss and phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty. Moving onto Saussure’s linguistics, Marcuse’s social criticism, leading to a layover in Lacan: anamorphosis, (erotic projection in the gaze) which for Lacan, “is sort of like the phallus... from an organic standpoint... that’s not a thing that lasts very long... It is the sign of the impossibility of satisfaction.” Terrain Derrida is next on the itinerary, ecriture, do we speak or are we spoken? On then to the Spectacle with Debord, and we see the revolution die.

There’s more – Foucault, Barthes, Deleuze, Ranciere among them.

Overlaying the deeper structural examinations of logic, linguistics and ontologies, we get glimpses of place: cafes of Saint Germain-des-Pres, Les Deux Magots of course, Camus’s Tipaza, “a beautiful little Roman garden outside of Algiers; it is just stunning in the sun and the heat,” Jameson records. There are even visits to the movies – Godard’s Breathless, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, examples of theory’s influences.

Of women though, there is not so much to see. Beauvoir and Kristeva are sketched in. Melanie Klein gets a mention in relation to Luce Irigaray. But it’s as though these women were working on an even playing field – no mention, for instance, of Lacan kicking Irigaray out of his famous seminar in a misogynistic fug. In film theory, Agnes Varda is missed; Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman is another loss.

Caveats aside, in our age of the portal onto all knowledge – the internet – this book directs the reader to a fund of riches, easily accessible. Jameson peppers the chapters with book and article recommendations, from SF to neuro science, ancient philosophy to media studies, the initial disturbance of an idea rippling outwards towards an archive of invaluable creativity.

This book is an autodidact’s dream. Under the generous direction of Fredric Jameson’s long life of critical thinking, why not just go to bed with a carton of Gauloises Blondes and a box of books. And come back when Trump is over.