This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

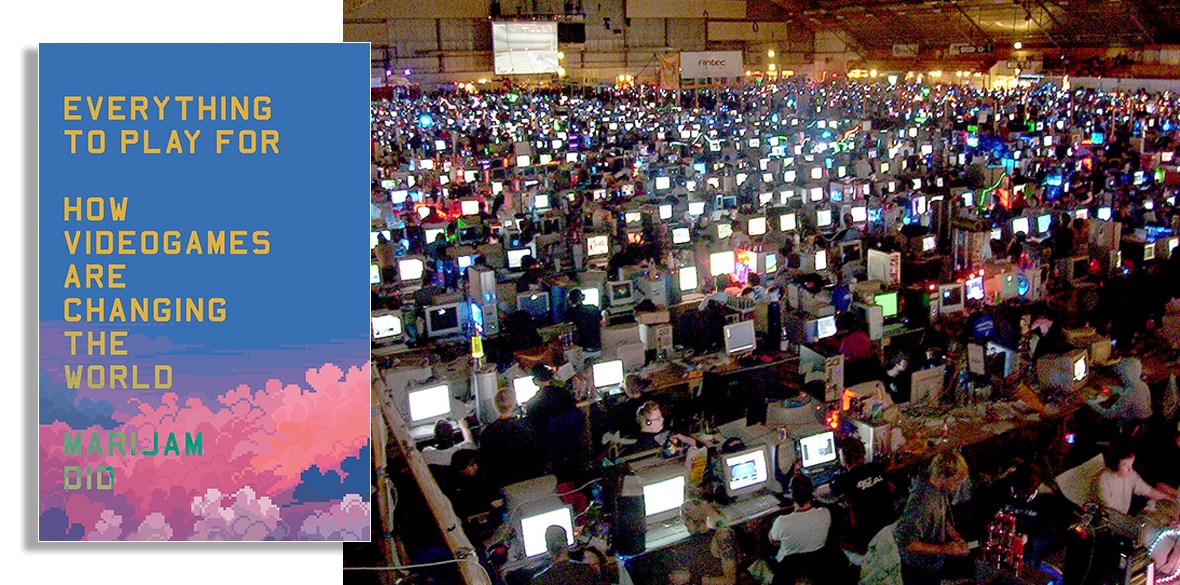

Everything to Play For: How Videogames are Changing the World

Marijam Did, Verso Books, £16.99

CAN video games be a force for good in the world, or are they the virtual precursors of our own destruction? Is there time to course correct, to instigate revolutionary changes in the industry, or are we racing ineluctably towards the worst digital culture has to offer?

These aren’t easy questions. But they do need asking — and as developers and players, we’re encouraged to hold ourselves accountable.

In reading Marijam Did’s Everything to Play For, I couldn’t help but feel uncomfortable.

As a video game developer and communist, aspiring to make some small difference through the arts, I’d stop suddenly and shake my head, almost as if I’d been wrongfully accused.

Am I one of those developers the author writes about, leveraging social capital? I hope not. But are the video games I’m developing, or hoping to develop, efficacious? Will they help smash those insufferable modes of capitalist production? I don’t know. Could I look a child labourer from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the eye while they toil at gunpoint and dig for coltan? Have I ever really considered where the rare earth elements of my computer or smartphone came from? There, it’s a shamefaced “no.”

It’s in this line of interrogation that the author’s at her strongest. For those of us making video games, Everything to Play For is a necessary wake-up call. An invitation almost. Dialectics in action. Moreover, given the fact that Did has a background in video game development, her writing also has the added weight of a workers’ inquiry — something which has been severely lacking in the past.

Still, the book’s not about instilling a sense of guilt. Rather, it’s about acknowledging the industry’s problems. All the myriad and endemic grotesqueries that suffocate creativity and malform society in the most insidious, intentional manner possible.

As Did herself explains, it’s first and foremost a “love letter.” Her writing is by turns playful and personal, optimistic and indignant, but never lost in despair. Thankfully, she helps us on our way with a number of thought-provoking, tendential approaches.

In the third chapter — one of five gamified “levels,” ranging from a materialist history of electronic play to a “final boss” fight — there’s a discussion on the instrumental potential of video games. This is an idea Did explores in depth, with references to the shock tactics of modern performance art; a trend already gaining traction with indie video game developers. Design choices combining the element of “surprise” and player “complicity” are capable of disseminating powerful emotive angles. Challenging assumptions. Their strength isn’t in platitudes and affirming shared ideologies but in their ability to reach, and even influence, those with contradicting views.

That said, there’s a hesitancy and scepticism on the subject of social and socialist realism. “How can games become tools for social change rather than mere statements or pieces of propaganda?” Did asks. Does that mean statements and propaganda aren’t tools for affecting social change?

The propagandistic impact of Maxim Gorky on Soviet Russia or, say, the more declarative works of Emile Zola on the Second French Empire and Ken Loach on Thatcher’s Britain aren’t quantifiable. Might they have made a meaningful difference? Can the projection of soft power in a Gramscian war of position lead the left to cultural hegemony? And if not, where do we go? What is to be done?

The fact remains that the video game industry is ethically compromised, and Did is absolutely on point when she calls for action. It needs burning down. Rebuilding from the bottom up. Everything to Play For is unequivocal on that, which is why anyone remotely interested in the global video game phenomenon should read it.

“The future,” Did concludes, “is not decided. It’s ours for the taking.”