This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

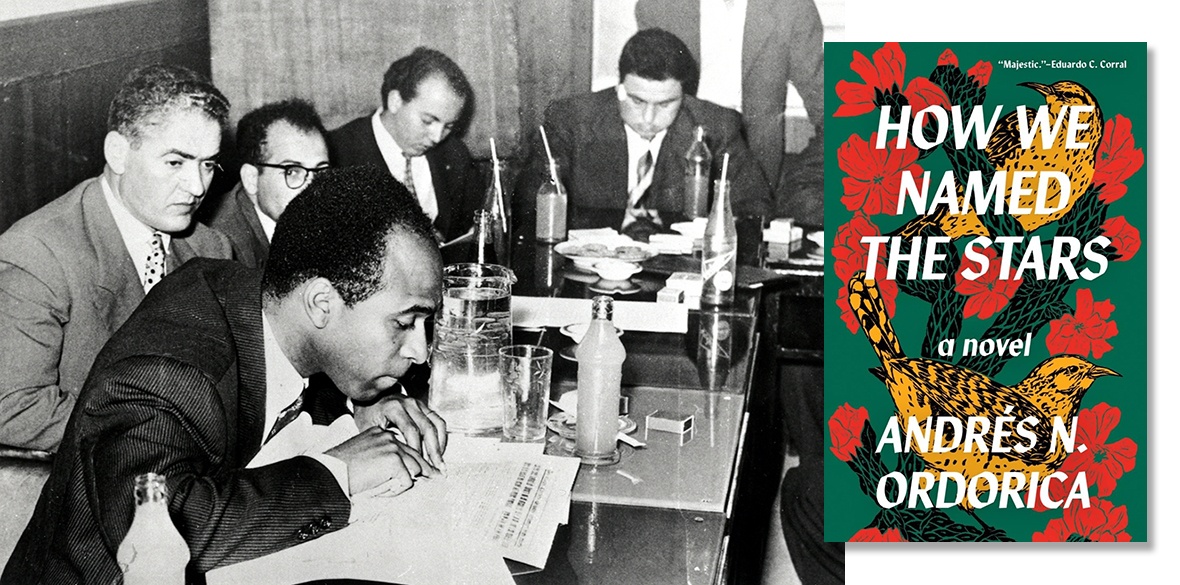

EVEN if Andres Ordorica’s Young Adult coming-out novel How We Named The Stars (Saraband, £10.99) didn’t mention Frantz Fanon, his shadow would fall across it.

It is a subjective account — like that template for YA fiction, Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye — that describes a 19-year-old Mexican American’s tragic crush on a white room-mate in his first year at university. His parents are first generation Mexican immigrants, but his culture and language is entirely that of the contemporary US.

He is “brown,” but his crush is an amalgam of gay white stereotypes: “washboard” abs, square chin, blond hair, blue eyes, a “gazelle” in Nike sweatpants and Timberland trainers — less a person, in other words, than a poster and a clothes rack. This “white” object of desire is both idealised and commodified, a blank cipher into which, it is presumed, the adolescent gay reader, white or otherwise, can project their own desires and fantasies.

So, black skin and white mask, as Fanon put it.

By “mask” Fanon, the psychiatrist and revolutionary means “the mastery of language for the sake of recognition.” He further elaborates with characteristic pugnacity that this “mastery” is “a performance of whiteness that reflects a dependency that subordinates the black’s humanity.” The way that the narrator thinks and expresses himself commits him to a peripheral role in the coloniser’s culture, and his “blackness” is wished away.

Ordorica’s narrative plays out and justifies this subordination. The Mexican is a neurotic, forever “overthinking” and doubting his own motives. After a year of hesitancy on the US campus the pair have sex with the Mexican in the subordinate role, and then split up.

Thereafter, the Mexican returns to his extended family in Chihuahua for the summer where he meets a gay Mexican with whom he has a romance but this time with no colour bar and no prolonged hesitation born of internalised homophobia. It is altogether more fulfilling and the protagonist is astonished to be recognised for his brown skin, brown eyes and black hair — the revelation of his natural “blackness.” He examines his own face in the mirror.

Then comes the news that his rejected white crush has died in a car crash and, after a pause, his neurotic white mask reinstates itself and reclaims his identity. He rejects his Mexican lover as “bad” and returns to the US to mourn the loss of his “good” ideal in public. He will, in words that Fanon laces with contempt, “save his race by making himself whiter.” The attraction of a “queer” identity and a racially subordinate role within the economically dominant culture eclipses his chance for authenticity, equality or political awakening.

Based on personal experience and devised with a US agent and publisher for a US market, this awkward internalisation of racism is now a recommended YA bestseller.

But the odd thing is that Ordorica does mention Fanon.

At a party for graduates that the freshman has gate-crashed, one of them “had read us part of The Wretched of the Earth in her seminar ‘The Philosophy of Activism’. Kelis smiled before continuing. ‘You should read him sometime if you haven’t. It’s important we begin to emphasise BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and People Of Colour] voices in the curriculum here. Enough with the classics being so male, stale and pale’.”

So, why doesn’t the narrator follow the advice? What is it about the academic environment and its privilege that allows Fanon to be alluded to but his insights ignored? Is academic anti-racist chatter part of the white mask?

In Black Skin White Masks (Penguin Modern Classics, £9.99) Fanon makes the critique of a novel with the very same plot — Je Suis Martiniquaise by Lucette Ceranus — that describes the tragic romance of a black woman with an idealised white man and Fanon doesn’t mince his words, condemning it as colonial literature and “cut-rate merchandise, a sermon in praise of corruption,” and the same critique applies to Oroduro’s novel. As Fanon points out, the basic conception of the world is manichaean, split between white and therefore good, and black which is bad.

I asked the author if his novel was more about race than gender identity or sexuality. Ordorica replied that this would be “a generous reading.”

But Ordorica is also an accomplished writer and the book — ostensibly a progress towards maturity — can also be read convincingly as the self-portrait of a self-deluding neurotic and, in the context of Trump’s racist policies towards Mexican immigrants, this perspective is more rewarding.

Transposing Fanon’s tale of corruption from heterosexual to homosexual terms it re-examines the fatal attraction of whiteness from the point of view of the racially other, idealising it to the point of fetishising it. And it has a dramatic Fanonesque moment when the narrator learns of his idol’s death and, fascinatingly, loses his ability to speak. This is the moment of potential authenticity from which his misconception of identity and desire can be rebuilt. That the narrator emerges from this to reject “blackness” and commit himself to a necrophile idealisation of his dead idol is the explanation of why the novel exists at all, and the story can be read as a cautionary tale.

I asked Ordorica, himself Mexican American like his character, if this is a legitimate reading. “I’m not interested in ‘authenticity’”, he replied. “What does it even mean?”