This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

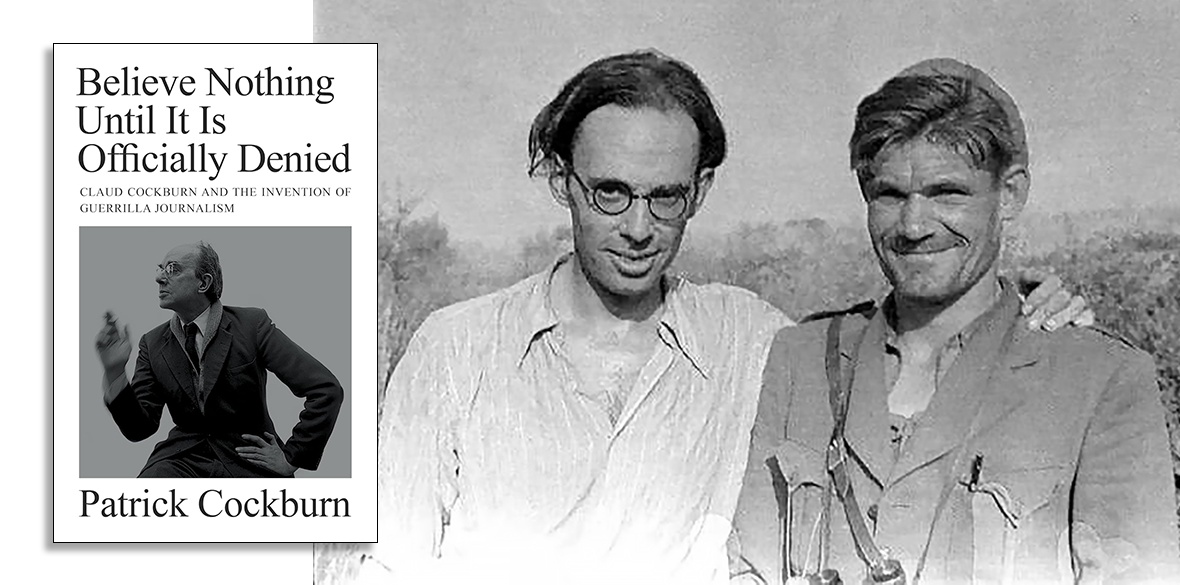

Believe Nothing Until It Is Officially Denied

Patrick Cockburn, Verso, £30

THE title of the book, Believe Nothing Until It Is Officially Denied, is a phrase credited to Claud Cockburn which has become the mantra for journalists the world over.

Claud Cockburn, the son of a Foreign Office diplomat, went to Berkhamsted school in Hertfordshire, then on to Oxford University, where he was close friends with novelist Graham Greene. He was also related to Evelyn Waugh. But that where the conventional establishment formation ends.

Claud and Greene travelled in the Europe of the inter-war years, seeing much devastation and importantly witnessing the rise of fascism. Claud became a reporter for the Times in Europe, and then in the US. He was highly valued by the then Times editor, Geoffrey Dawson, and the management. But in 1932, he struck out on his own, creating a shoestring operation, The Week magazine, a kind of newsletter, breaking news not seen anywhere else. It had a small circulation but, with excellent inside sources, was essential reading and particularly in relation to what was happening in Europe with the rise of the Nazis in Germany and the Spanish civil war.

Claud reported directly via his own eyewitness accounts and connections. His wide range of contacts ensured important insights. He also joined the Communist Party and reported for the Daily Worker for many years, remaining a communist for the rest of his life.

One of the important themes he cast a light on was how media and politicians in Britain and beyond were colluding in the policy of appeasement towards Hitler. He exposed the role of the Cliveden set, around the Astor family, which by the 1930s owned the Times and much of the media, in helping foster support for this policy.

Government policy at the time (1930s) was not to offend the Nazi regime. Also, at the time, the editor of the Times constantly altered reports so they were not overly critical of Hitler.

Claud’s form of guerilla journalism involved using all weapons at his disposal to expose what was going on and the approaching catastrophe, and he seemed to attract opprobrium from all sides. MI5 were constantly monitoring his activities, yet he also managed to annoy Stalin and Kremlin chiefs. This can perhaps be taken as confirmation that he was getting it right in terms of journalistic balance.

Author Patrick Cockburn obviously had a ringside seat in his father’s life. An excellent journalist himself, Patrick provides a highly insightful commentary.

Pulling things together, he highlights how The Week was a unique journalistic instrument for the 1930s. But once Claud had revealed the truth the role of The Week ceased. However, his guerilla journalism continued in other forms, post war. He played a big role in the creation and success of Private Eye. He also worked for Punch in the 1950s, when it became more rebellious under Malcolm Muggeridge's editorship. He also contributed columns and commentary across the international media.

Patrick Cockburn adjudges that journalism in the 1960s and ’70s was less restricted, and more capable of doing the job of bringing the ruling cliques to account. However, for most of the time, the great mass of media remained just a PR extension of government and capital. Never has this been more so than today, particularly in the reporting of conflicts like Gaza and Ukraine. Indeed, author Patrick suggests that Claud’s guerilla style journalism is needed as much today as in the 1930s.

And we are beginning to see it via the likes of Novara Media, the Canary and of course the Morning Star. Publications like Private Eye play a part, as do individual journalists embedded in the mainstream media.

One interesting quote from Claud on the need to speak truth to power was that truth needs to be spoken to the powerless, in order that they maybe empowered to act.

Patrick Cockburn has produced a fascinating book about his father’s life, with some excellent insights relevant to journalism today. A great read for all but a compulsory text for any aspiring journalists out there.