This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

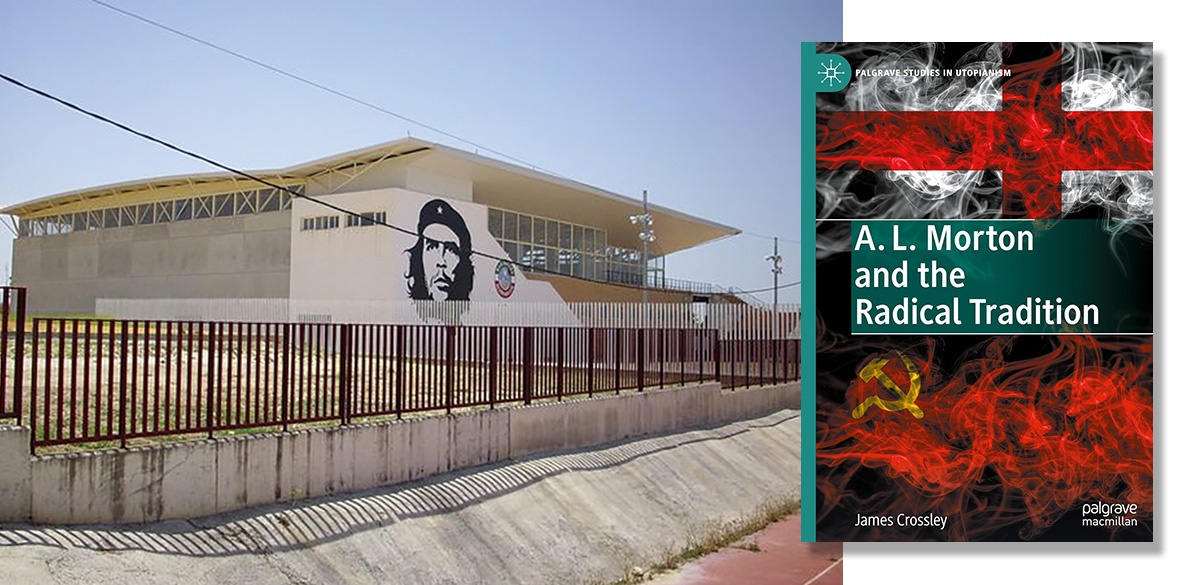

A L Morton and the Radical Tradition

James Crossley, Palgrave Macmillan, £89

JAMES CROSSLEY has done it again. With A L Morton and the Radical Tradition, he delivers a masterful biography that not only resurrects the life and legacy of a pivotal figure in British radical history, but also revitalises the study of English political thought.

Crossley, known for his incisive explorations of figures as diverse as Jesus and John Ball, turns his scholarly gaze to Arthur Leslie Morton, a historian, activist, and intellectual whose work shaped the socialist imagination for generations. This book is not just a biography; it is a vibrant excavation of the radical tradition itself, told through the life of a man who was both its chronicler and its champion.

Morton is best known for his seminal works, A People’s History of England (1938) and The English Utopia (1952). The former, a sweeping narrative of English history from the perspective of the common people, has been a gateway to socialism for countless readers, including this reviewer. Crossley’s study reveals Morton not merely as a historian of radicalism but as a participant in its unfolding drama.

Born in 1903 in Bury St Edmunds, a crucible of historical radicalism, Morton’s early exposure to Shakespeare and the works of William Morris and Jack London planted the seeds of his lifelong commitment to socialism. His time at Cambridge University further radicalised him, bringing him into contact with figures like Maurice Dobb and Maurice Cornforth, who would shape his intellectual and political trajectory.

Crossley’s narrative is richly detailed, drawing on extensive archival research, including Morton’s recently declassified secret service files. These files, released in 2017, reveal the extent to which Morton’s activism and writings were seen as a threat by the British state. From his involvement in the General Strike to his reporting for the Daily Worker, Morton’s life was one of relentless engagement with the struggles of his time. Crossley deftly weaves these threads together, showing how Morton’s activism underpinned his scholarship and vice versa.

Crossley reveals how, in the 1930s, labour movements globally faced a life-and-death struggle against fascism, which sought to co-opt popular history, traditions, and imagery. In Britain, the Communist Party played a pivotal role in thwarting this, forging broad alliances to win the battle of ideas on a cultural front. Morton was central to this effort, rescuing popular history from fascist appropriation at a critical juncture.

One of the book’s great strengths is its exploration of Morton’s intellectual contributions. Crossley highlights Morton’s ability to think beyond conventional boundaries, whether in his analysis of the English Revolution, his reinterpretation of Cromwell’s role, or his groundbreaking work on utopianism.

Morton’s The English Utopia is particularly significant, as it traces the utopian impulse in English history and its influence on working-class movements. Crossley, an expert on utopianism himself, argues that Morton rescued utopian thought from derision, presenting it as a vital bridge between religious idealism and materialist politics. This insight alone makes the book essential reading for anyone interested in the history of radical thought.

Crossley also sheds light on Morton’s lesser-known contributions, such as his role in the Communist Party Historians’ Group, where he worked alongside luminaries like Dona Torr, Victor Kiernan, Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, and E.P. Thompson. This group revolutionised the study of history from below, emphasising the power of ordinary people and the importance of local studies. Morton’s collaboration with Donna Torr on Tom Mann and His Times and his own History of the British Labour Movement further cemented his reputation as a historian of the people.

But Morton was more than a historian; he was a cultural critic and a visionary. Crossley reveals how Morton’s engagement with figures like William Blake and the Bronte sisters allowed him to critique the co-optation of radical culture by bourgeois ideology. Morton’s warnings about the corrosive effects of individualism and consumerism, particularly in the realm of culture, resonate powerfully today.

Crossley argues that Morton was not a conservative but a man ahead of his time, whose critiques of consumerism, postmodernism and environmental degradation anticipate contemporary concerns.

The book also delves into Morton’s later years, including his opposition to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and his continued activism against US military bases in the East of England. Crossley portrays Morton as a man of unwavering principle, whose commitment to revolutionary change never buckled, even as he recognised that such change would take generations to achieve.

Crossley’s prose is both scholarly and accessible, making A L Morton and the Radical Tradition a joy to read. He has sifted through an enormous volume of material to present a coherent and compelling story, one that does justice to Morton’s complexity and enduring relevance. This book is not just a tribute to Morton but a call to rediscover the radical tradition he championed.

A L Morton and the Radical Tradition is a triumph. It is a must-read for historians, activists, and anyone interested in the enduring power of radical ideas. Crossley has given us a portrait of a man whose life and work remain vital to understanding our past and shaping our future. If you haven’t yet read Morton’s A People’s History of England or The English Utopia, let this book be your gateway. And if you have, let it deepen your appreciation for the man behind them.

James Crossley has done Morton — and us — a great service.

The retail price of the book at £89 will keep it out of the hands of most Morning Star readers. But do not be put off, place an order and lobby for it to be available from your local library.