This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

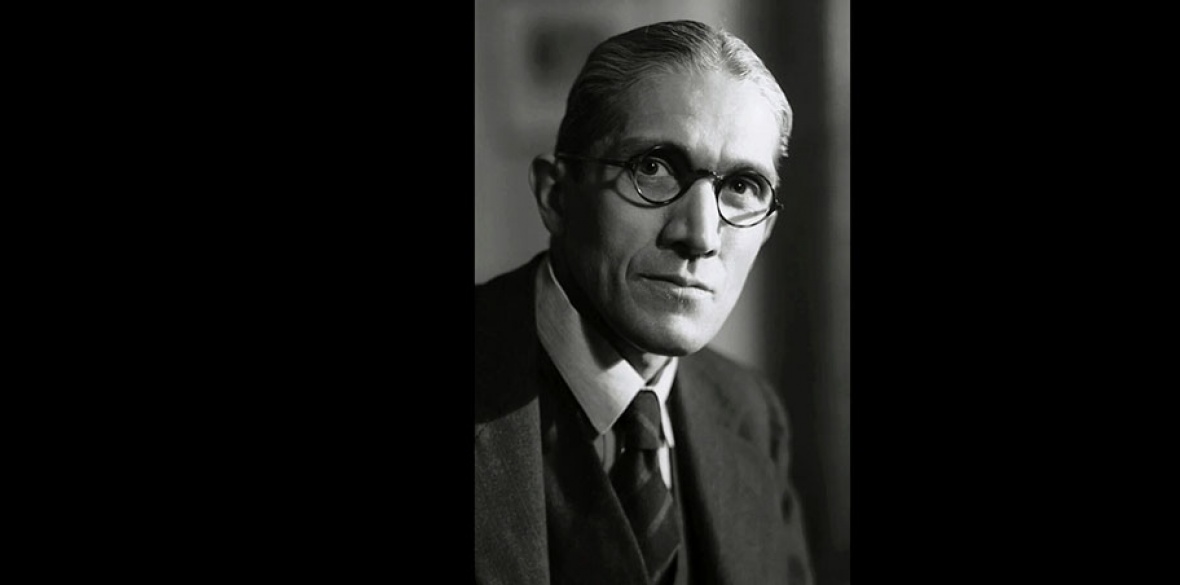

FIFTY years ago today Rajani Palme Dutt passed away, depriving British Marxism of one of the most powerful and militant intellects of its history.

A founder of the Communist Party and one of its leaders for over 40 years, Dutt was a remarkable theoretician whose achievements stand out the more sharply against the background of the preponderant pragmatism of the British labour movement.

He was probably best known internationally as the editor of Labour Monthly from 1920 until his death, guiding a journal which was not only a forum for united front and broad left politics but also home to Dutt’s own invariably-penetrating “Notes of the Month,” which gave readers a panoramic perspective on the class struggle in Britain and globally.

Dutt was also the author of many books full of Marxist insight. Two in particular stand out.

In Fascism and Social Revolution published in 1934, he located the ascent of fascism in the post-war world crisis of capitalism and in particular highlighted the way in which social democracy prepared the way for fascism, above all by splitting the labour movement and abandoning the struggle for socialism.

And in 1952’s Crisis of Britain and the British Empire, he drew out the connections between the world policy of British finance capital and the problems besetting the British people, in particular the advancing danger of war.

While there can be no direct read-over from the 1930s or the 1950s to today, the relevance of both books to contemporary struggles is evident.

Dutt was no armchair thinker, however. He helped lead British Communists, alongside Harry Pollitt and Willie Gallacher, from the front; ascending to the highest levels of the Communist International.

Dutt became de facto general secretary of the Communist Party in 1939 when it opposed the imperialist war policy of the Chamberlain government, holding the post until June 1941.

Controversial as this was at the time and since, Dutt never regarded the position as an error – unlike the excesses of the class against class approach, which dubbed reformists “social fascists,” 10 years earlier. This line, which he had vigorously championed, he later held to be a serious misestimation of the situation.

The Cambridge-born son of an Indian father and a Swedish mother, he championed the cause of anti-imperialism his entire life, from opposing the first world war through to post-war struggles for colonial freedom.

Indian independence was a particular focus of his endeavours, and his memory is held in the highest esteem by Indian communists to this day.

Dutt regarded himself as, politically, a child of the October Revolution, and never wavered in his solidarity with the Soviet Union. He acclaimed the Chinese revolution too, although when the two great Communist parties of the world divided in the 1960s, it was with sadness but not hesitation that he supported the Soviet.

In such a long revolutionary career, with so much committed to publication, it is not hard to find misjudgements and points to criticise. His dismissal of Soviet criticisms of Stalin in 1956 – “spots on the face of the sun” – caused much hand-wringing.

Dutt was of his time, and it is in many ways not ours. His political points of reference have changed or even disappeared over half a century.

But in his fundamental attributes – an unswerving commitment to socialism, a lifelong effort to master and apply the Marxist method, and the centring of workers’ internationalism – he is forever contemporary.

No-one advanced, within the Communist Party or outside, to adequately fill the gap he left. It must remain perforce a collective effort. Today, we salute the memory of a great Marxist leader.