This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad

Simon Parkin, Sceptre, £25

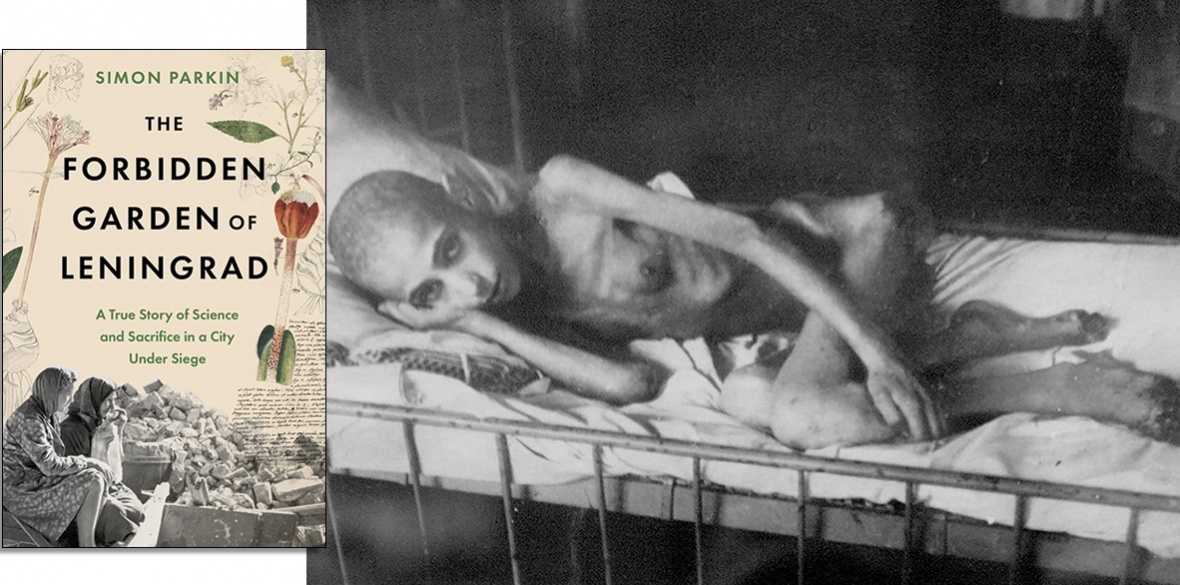

IMAGINE being faced with the very real dilemma of whether you should eat your life’s work in order to survive. What if that life’s work was the very struggle against hunger itself. The scientists at the All Union Institute of Plant Breeding faced just this dilemma as they endured the longest and most brutal siege known to humanity, surrounded by the world’s first and greatest seedbank.

In 1941 the Plant Institute in Leningrad – a requisitioned palace filled with every variety of grain, potato, pulse and fodder – was at the heart of a city besieged by the armies of Nazi Germany. For nearly 900 days Leningrad held out against fascism in one of the most crucial stands of the second world war. Simon Parkin has produced a pacy and dramatic account of the Siege of Leningrad, centring on the scientists in the city, and the ordinary and extraordinary decisions they made in order that their work would survive.

Reconstructed from the records and diaries of the city’s botanists, The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad provides a riveting account of a city on the edge of starvation, and of the devotion to science and progress exhibited by the scientists trying to preserve all that they had discovered, in the face of Nazi brutality. At least 19 members of staff at the institute starved to death surrounded by these plants and seeds. Their belief in the value of their work to future generations, and the importance of breeding new super-crops that would help feed the Soviet Union, was so great that they endured death rather than sacrifice it.

Through their harrowing endurance, Harkin tells us that the Plant Institute was saved and that, by 1979, nearly 200 million acres of Russian land was planted with crops from their seedbank. Ninety per cent of the seeds held in the collection are found in no other seedbank in the world, and crossbreeds resulting from this collection continue to ensure food security across Russia and internationally. As Harkin puts it: “In kitchens and dining rooms around the world, people continue to benefit from the sacrifice of the men and women who gave their lives during the siege.”

Undoubtedly this is a story of heroism. It is a moving companion to the Leningrad Symphony, in which the 15 surviving members of the Leningrad radio orchestra braved cold and starvation to play Shostakovitch’s new work. Like the symphony, the plant institute represents the incredible will not just to survive, but to demonstrate the greatest attributes of humanity in the face of fascist barbarity. It may not have the cultural impact of the Leningrad symphony but, in its way, the struggle of these botanists contains all the flair, pathos and beauty of the music of the besieged city. Leningrad, after all, contained Russia’s artistic and its academic heart, and this is why Hitler wished to raze it to the ground.

This story however is not just one of academic and artistic resistance. It is a story of solidarity, of people doing that “simple thing that is hard to do,” as Brecht put it. It is a story of communism. Of people standing with and for each other in the face of terror, and lifting each other up. Parkin is in no way alive to these meanings, but instead frames it as individual valour in the face of the twin terrors of Stalinism and Nazism. In doing so he does a disservice to the very heroes he celebrates.

There is no question that the Soviet system and its ideals served as an inspiration for the selflessness of these scientists, and to acknowledge that does not require apologism. We can admire the solidarity and heroism of Soviet Russia without absolving it of its crimes. Harkin avoids such nuance. In striving to resist the communist hagiographies of authorised Soviet history he allows the pendulum to swing the other way and erases the political and ideological realities of the siege.

The decision to frame the book around Vasilov — the charismatic, almost Indiana Jones-style botanist — similarly plays into the individualism of the hero narrative and reduces many of his colleagues and comrades, leaving them as extras in the drama of this “swashbuckling saint.”

There is also an uncomfortable irony in Parkin’s criticism of Stalinist discrimination against upper-class scientists and his repeated description of the botanist Lysenko as “the peasant farmer.” Elsewhere Parkin describes the Bolshevik revolution as “a political coup.” Such an argument can perhaps be made, but when the author asserts that after the revolution’s “state-endorsed banditry led to a civil war” he lays either his ignorance or his bias bare.

Was it “state-endorsed banditry” that led the United States, Britain and France to attack the only worker-led nation in the world? Was it “state-endorsed banditry” that the landlords and Orthodox Church united to crush through massacres and pogroms? Such a misleading claim undermines the central opening story of a young and idealistic botanist travelling across a famine-wracked country by fundamentally misrepresenting the revolutionary moment in which he lived.

One of the survivors of the siege at the Plant Institute, Lekhnovich, recalled that it was not at all hard to starve rather than consume the seed collection. He said: “It was impossible to eat it up, for what was involved was the cause of your life, the cause of your comrades’ lives.” The word comrade seems alien to Harkin and when he repeats the quote a few pages later he tellingly renders it as “colleague” not “comrade.”

These narrative and methodological failings are countered to some extent by a brilliantly and adventurously structured timeline that paints Leningrad as a city in the throes of multiple overlapping crises and in doing so refreshes the endlessly moving story of its stand against fascism. As a vivid and engaging portrait of the siege there is much to appreciate in this book, though some of it seems to elude its author.