This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“IT is worse, much worse, than you think.” So begins The Uninhabitable Earth: A Story of the Future, David Wallace-Wells’s brilliant new book on the existential threat of climate change which, judging by its frightening contents, should be placed next to Stephen King in the horror section of every bookshop.

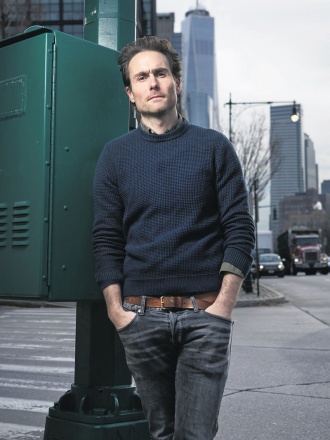

“I don’t come to it with a life of attachment to environmental causes,” Wallace-Wells, 36, tells me when I ask him about his initial interest in the subject when we met in a central London hotel last month.

“Five years ago I would have said climate change was an important issue and we should be addressing it but I didn’t understand it was a totalising challenge that actually governed all of the other political goals that we might have in this world.”

He says he has been “completely transformed” by his research and writing on climate, which received national and international attention with his 2017 article in New York Magazine, where he is deputy editor. Quoting climate scientists, the article — which has the same title as the book — looked at some of the likely effects of the worst-case scenarios in terms of global temperature rise. It became the most read article in the history of the publication.

“There was a vocal minority of scientists who took issue with it,” Wallace-Wells concedes. “So I wanted to really rigorously focus the book on a smaller range of possible outcomes. In the article I was talking about warming up to 5, 6 and even 8°C. In the book I mention those levels a couple of times but it’s very much focused on 2°C to 4°C, which is inarguably the boundaries of reasonable contemplation.”

For the uninitiated, these figures refer to the increase in global temperature on pre-industrial levels. The world has already experienced a 1°C increase. At the 2015 UN climate conference in Paris the 195 signatory nations pledged to keep global warming to “well below” 2°C and “endeavour to limit” them to 1.5°C. However, speaking to the Morning Star in 2016, the respected climate scientist Professor Kevin Anderson explained the commitments made at the summit would likely lead to 3-4°C of global warming by 2100.

Despite the book’s narrower focus, its conclusions — based on hundreds of references to the latest scientific research — are still horrifying. “Warming of 3 or 3.5 degrees would unleash suffering beyond anything that humans have ever experienced,” Wallace-Wells writes. And just to scare you further, it’s important to understand that the larger the temperature increase, the more likely feedback mechanisms and the sheer complexity of the world’s climate system will lead to runaway climate change that humanity will be unable to control.

“At 4°C of warming we will have made inevitable the total collapse of all the ice sheets on the planet, which will mean, over time, at least 50 and probably 80 metres of sea level rise,” he tells me. “That will take centuries to unfold but it will mean millions of square miles of coastline underwater, many of the world’s biggest cities completely drowned” and “will literally redraw the map of the world and make the planet unrecognisable in many, many ways.”

Turning to the dire effects of heat, he notes “it’s possible as soon as 2050, when we will be at about 2°C of warming or a little bit warmer than that, that many of the major cities in India and the Middle East will be lethally hot in summer. You won’t be able to reliably go outside, work outside during the summer months without incurring some lethal risk.”

He believes this will contribute to an unprecedented global refugee crisis, and notes in 2017 the UN estimated climate change might create as many as a billion climate refugees by 2050 — “which is as many people as today live in North and South America combined.” He is careful to qualify this, explaining the UN’s estimate is very much at the high-end of projections: “Even if we only get to 75 million or 100 million that’s a refugee crisis many times bigger than anything with ever seen before.”

The evidence points to “dramatic” economic impacts too, he argues. “The best research suggests at about 4°C of warming we will be dealing with the global economy… that was 30 per cent smaller than it would be without climate change. That is an impact twice as big as the Great Depression. And it would be permanent.”

With the effects of climate change so serious and all-encompassing, the environmental movement has long debated how best to present the facts and dangers to the general public in a way that will engender engagement and action. The consensus, in the UK at least, has been for messaging fixed around notions of hope and positive visions of the future.

For example, speaking at a World Development Movement public event in 2008 Green MP Caroline Lucas argued “the rhetoric of fear and disaster and tipping points is deeply scary, and it’s deeply unhelpful.”

“It doesn’t work to try to terrify people into action,” she continued.

Wallace-Wells, as readers of his book will attest, takes a very different position: “As I look out at the world it just strikes me that although there are some people are at risk of being pushed into despair and fatalism, the number of people who are living complacently in the modern world about climate is just so much bigger.”

Careful not to dismiss hopefulness and optimism — “anything that sticks” is good — he points to the history of environmental activism and political mobilisation to back up his argument. The influential role Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring had in banning DDT pesticide, drunk driving and anti-smoking campaigns — all of these successes were not accomplished “by messaging optimistically and talking about hope” but were based on fear and alarm, he argues.

He also points to the historic recommendation of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change last year — that to stay below a 1.5°C temperature increase the world must immediately embark on a World War II-level mobilisation to shift away from fossil fuels. “There were threads of hope and optimism that was part of that [the mobilisation in World War Two] but there was also, obviously, a lot of fear and panic and alarm about what would happen if we didn’t mobilise,” he says.

While The Uninhabitable Earth is certainly alarming, Wallace-Wells himself is hopeful about the future in many ways, highlighting new activism such as Extinction Rebellion and 16-year-old Swede Greta Thunberg and the global school strikes she has inspired.

He also points to significant shifts in US public opinion, with a recent Yale University/George Mason University survey finding six in 10 in the US were either “alarmed” or “concerned” about climate change, with the proportion of people “alarmed” having doubled since 2013.

Turning to US politics, he is excited that the Democratic Party is “effectively and totally” signed on to the Green New Deal, the proposed economic stimulus programme that reiterates the goals of the UN to hold global warming to 1.5°C. Mirroring what happened with Heathrow expansion and UK politics in the mid-2000s, he notes the Green New Deal has become “a kind of litmus test for any Democratic candidate” for president, with climate change likely to be a first order priority alongside healthcare and education in the Democratic primaries.

”I even think that will impact the Republican Party over time,” he predicts.

Looking at the big picture, in the book Wallace-Wells maintains the climate chaos which is now upon us “has been the work of a single generation.” The generation coming of age today faces a very different and essential task, he believes: “the work of preserving our collective future, forestalling… devastation and engineering an alternate path.”

“We are living in incredibly consequential times. What we do now politically, culturally, economically will determine the — not to put it too bluntly — habitability of the planet going forward,” he tells me. “Humans have never been in that position before, never held that kind of power in our hands before.”

The Uninhabitable Earth: A Story of the Future is published by Allen Lane, priced £20. Read Ian Sinclair’s review of the book here.