This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

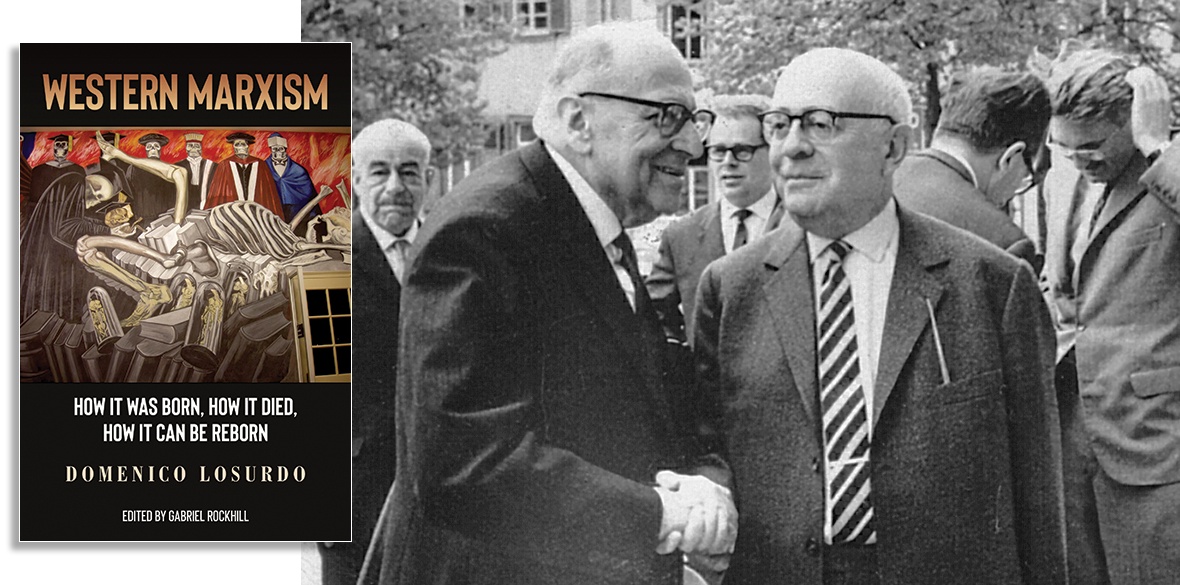

Western Marxism: How It Was Born, How It Died, How It Can Be Reborn

Domenico Losurdo, Monthly Review Press, £20

THIS is an important book on an important subject. For some who, like this reviewer, failed to see the relevance of much academic Marxist discourse in the 1970s and ‘80s to their own political activity it will offer some reassurance: there wasn’t much.

First published in 2017, this first English translation of Italian communist philosopher, historian and politician Domenico Losurdo’s text is a trenchant criticism of a school of intellectual discourse from the “Frankfurt School” of the 1930s onwards.

Losurdo begins by documenting the separation of “Western” from “Eastern” (sometimes “classical” or ‘orthodox”) Marxism especially in relation to the latter’s development after the 1917 October Revolution. Following the failure of revolution to spread throughout Europe some left intellectuals were unable to come to terms with the contradictory realities of building a state capable of resisting its encirclement by imperialism.

Intellectuals and political dissidents associated with the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research (founded in 1923) — including Max Horkheimer (from 1930 its director, who relocated it to the US during the Nazi period), Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, and Jurgen Habermas — retreated into a Eurocentric analysis of the social and political superstructure of capitalist society. Through selected quotes their work, together with that of other luminaries such as Michel Foucault and Antonio Negri, Losurdo subjects them to a sustained critique for their Eurocentric blinkers and their dismissal (or ignorance) of the way that the consolidation of power in what became the USSR inspired anti-colonial revolutions elsewhere, not least in China, Vietnam and Cuba, as well as Africa and Latin America.

A particular target is Hannah Arendt, in her move from the left to her Cold War identification of the USSR under Stalin with Hitler’s Germany as equal in “totalitarianism.” Another is Slavoj Zizek whose (fading) popularity amongst students new to Marx and Marxism is sometimes held to be a revival of Western Marxism, but which Losurdo declares is — together with Zizek’s support for Nato’s proxy war against Russia and his dismissal of Cuba’s difficult task of building socialism — its “last gasp.”

Losurdo’s critique is summarised in an introduction by the book’s editor Gabriel Rockhill, written with Jennifer Ponce de Leon. They assert that the whole of Western Marxism represents a withdrawal from action to change the world into the academy; a shift away from political and economic issues (especially those of class and imperialism) in favour of philosophic and aesthetic concerns characterised by “Eurocentric social chauvinism... the dogmatic rejection of actually existing socialism... a celebration of marketable novelty at the expense of practical relevance, and self-promotional opportunism that perpetuates cultural imperialism and disdain for Marxism in the global South.” For its exponents, they argue, “the exchange value of Marxist theory,” augmented (of course) by “Western Marxism’s novelty and originality, is more important than its use value for human liberation.”

Losurdo’s approach has some faults. Much of his argument is built around an eclectic but selective paste-in of quotations, for many of which (as pointed out by the editors) no sources are given. He rightly criticises Western Marxists for appropriating the work and names of Gyorgy Lukacs and Antonio Gramsci, both of whom were committed communists. But he also dismisses Perry Anderson whose 1976 book popularised the term “Western Marxism” and whose critique of its development anticipated (in gentler terms) some of Losurdo’s own condemnation (though arguably from a Trotskyist position).

Importantly, Losurdo largely ignores those western (small ‘w’, including interwar British) communists – including those who risked their own lives (in Spain from 1936-38 to South Africa in the 1960s and ‘70s) — as well as Marxist historians, economists and natural scientists whose work engaged with the “base” as well as its “superstructure.”

Nevertheless Western Marxism makes convincing argument. Its conclusion cites a popular and influential book by a self-proclaimed Marxist that invites us to “change the world without taking power.” “Here,” declares Losurdo, “the self-dissolution of Western Marxism ends up departing from the terrain of politics and settling in the land of religion.” Losurdo is clear that “changing the world” involves an intensification of anti-colonial struggle, and an ongoing renewal of Marxism, not limited to any hemisphere.