This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THOUGH he only made 40 recordings, US blues artist Robert Johnson’s legacy has endured for over eight decades and his songs are now part of the blues canon.

Those recordings — some were never issued and others were alternate takes — were made in 1936 and 1937, yet even with such a modest catalogue Johnson’s influence has stretched from the late 1930s to the post-war Chicago blues era of Muddy Waters, Elmore James and Howlin’ Wolf through to the 1960s, 1970s and beyond.

The list of the great and the good who’ve interpreted Johnson’s material is pretty endless. Cross Road Blues got a thunderous version by Cream at their 1969 farewell concert in London, while Love In Vain was covered by the Rolling Stones on the album Let It Bleed and I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom by Ike & Tina Turner.

Other interpreters have included Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac (Hell Hound On My Trail), Led Zeppelin (Travelling Riverside Blues) and Eric Clapton (I’m A Steady Rollin’ Man), not to mention the endless performances of Sweet Home Chicago, now a staple of every touring blues artist as well as every Blues Brothers show.

The myths and stories surrounding Johnson, his prowess as a guitarist, his untimely death and the search for a final resting place following his murder at the age of 27 in 1938 are the stuff of legend. The most enduring is that he sold his soul to the devil at a crossroads in Mississippi in order to become an extraordinary guitar player and that his shyness led to him recording facing the wall.

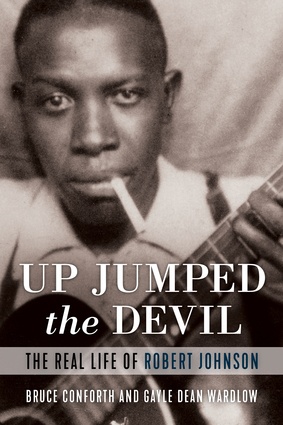

Johnson’s eventful and ultimately tragic life has long cried out for an authentic account and that’s exactly what the book Up Jumped The Devil, published next month, provides. It’s the result of over 50 years of research by blues writer Gayle Dean Wardlow and Bruce Conforth, who has studied Johnson’s life and music since 1970.

Between them, they provide much new information in a book that not only destroys every myth that ever surrounded Johnson but also details all his recordings, travels and relationships. This is his true story.

Johnson was already a brilliant guitar player from the get-go. He didn’t need to meet the devil to become one and he was already a popular performer of his own blues and the pop songs of the day. He recorded with his face to the wall as he didn’t want other musicians in the room to see his guitar technique.

And it was a liaison with a plantation overseer’s wife which led to his fatal poisoning with mothballs dissolved in a jar of corn liquor which caused near paralysis and severe bleeding from the mouth. The perpetrator is said to have only wanted to give Johnson a “warning” — apparently this sort of poisoning could be overcome! No surprise that he was quickly buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

He was originally contracted to record for Vocalion Records in 1936 by producer John Hammond, who was so enthused by what he had recorded and heard he wrote in the March 1937 issue of the communist magazine New Masses that Johnson was “the greatest Negro blues singer who has cropped up in recent years.” Compared to Johnson, the blues singer Leadbelly — a favourite of the New York left — sounded “like an accomplished poseur,” according to Hammond.

Johnson’s record sales were not high, with the exception of 1936’s Terraplane Blues, referencing the model made by the Hudson car manufacturers, but even so Hammond wanted him to appear at Carnegie Hall for the Spirituals To Swing concert in December 1938, featuring Count Basie, Big Joe Turner, Albert Ammons and the Golden Gate Quartet.

He was going to be the big surprise of the show but Johnson was already dead. Hammond wrote about Johnson’s demise in “unknown circumstances” in New Masses and read the article from the stage of the concert shortly after.

In 1961 and 1970, Columbia Records issued two Johnson albums with released and unreleased tracks but the clincher was the Columbia Sony box set issued in 1988. Expected to sell no more than 10,000 copies over five years, it sold hundreds of thousands in a few weeks and racked up more than 50 million sales in the US alone.

Since then, other CDs of his recordings have been released, from cheap budget releases to deluxe vinyl box sets costing hundreds of pounds.

In recent years, the Robert Johnson industry has cranked up. A silent film of a street performer, shot after he died, was hyped on eBay but there were no takers. US magazine Vanity Fair ran a feature on a photo bought on eBay of Johnson with Chicago bluesman and travelling companion Johnny Shines.

That story was picked up by the world’s media until it was proved that it was neither Johnson or Shines as both men were wearing “zoot” suits, not a popular style until the early 1940s.

There are in fact only three known photos of Johnson — a dapper studio portrait, a photo-booth picture which Johnson took and a photo of him with his half sister and her son.

There have been many books written about Johnson, but none have carried such weight of information and sheer detail, unearthed over the decades by Wardlow and Conforth. Not only have they roundly debunked many myths, they’ve come up with the definitive biography of one of the 20th century’s greatest and most influential musicians.

Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life Of Robert Johnson is published by Chicago Review Press. A documentary on Johnson, ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads, is currently available on Netflix.