This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

When the Apple Ripens: Peter Howson at 65: A Retrospective

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

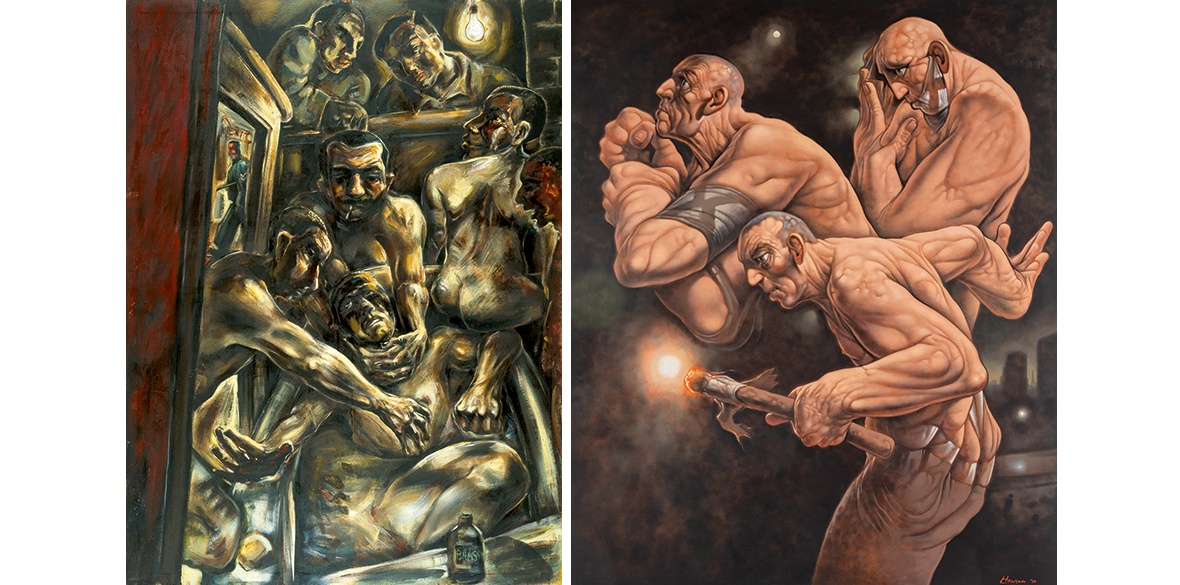

FROM the start, Peter Howson’s paintings have depicted men with exaggerated muscles, distorted limbs and grim, fanatical expressions.

In the exhibition When the Apple Ripens at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh there are only two drawings that are clearly made from life, and they feature his daughter depicted in the simplified neo-classical technique common to Alistair Gray, John Byrne, James Cowie and others, that hasn’t changed for a century in Scottish art and passes as the marker of “competence.”

So, he can do it in that artful and sketchy way from life, and the fact that his daughter has autism gives the sketch Park, 1992, that special Howson bite.

But mostly he doesn’t.

Rather, his painting has always leant on an alarmingly over-inflated cypher of imaginary masculinity. It is the basic currency of his vision, and he sticks to it relentlessly.

It derives, it seems, from leaving Glasgow School of Art aged 18 on the grounds that it was “authoritarian,” to join the British Army which (is this a surprise?) was genuinely authoritarian, and then filling in the subsequent years of young manhood with body building and working as a bouncer.

This established the lumbering muscled ogre-type as his dependable Everyman, and he sets it wandering through the East End of Glasgow as a boxer or a dosser; then he gathers them into thuggish groups of sometimes English, sometimes Russian, but never (at least in this show) Scottish nationalists; and eventually he multiplies them throughout densely populated apocalyptic landscapes.

Sometimes, as in the only directly political work on display here, he employs the white-skinned orc as an allegory of US/UK imperial violence.

This arresting painting has genuinely courageous political intent: it is a portrait by a Scottish artist of the naked beast that is Nato. It is also the only one of all his distorted balloon men to have a penis painted in and visible alongside a vast flotilla of US and UK flags.

The point, it seems, is to deploy an imaginary masculinity to depict its capacity for violence, and to give brutality a gender. So far, so conventional, but what is the cumulative effect of this massing up of muscled men?

While the bodies, often trussed in fetishistic harnesses, jostle and crowd one another, they never transmit affection. The hands, always exaggerated in proportion to bodies, are blunt tools and never sensitive instruments. And in place of empathy is an unremitting demonic energy, a misguided force.

Howson’s vision, in other words, may be inspired by Goya and Bosch (although it’s gym-pumped Bosch) but never by Diego Rivera whose murals are just as densely populated. Look for rationality, or look for love, and you look in vain. Rather, he deploys a bullish homophobic subtext to emphasise his satirical message.

This disconcerting distortion of Social Realism reaches back to the very birth of the genre in 1934, and the sexually repressive laws that accompanied it. This is the period between the underhand re-criminalisation of homosexuality in the Soviet Union in 1933, that prompted Maxim Gorki to declare in Pravda in 1934: “Destroy the homosexuals and kill fascism!”

In fascist Germany a separate but parallel process occurred following the murder of the Nazi SA leader Erich Rohm, a well-known homosexual who had become politically inconvenient, in which the Nazis persecuted homosexuality and decried “degenerate art.”

The situation in the UK was equally bad, and laws that criminalised homosexuality persisted in Scotland until 1981.

The subsequent taboo on any representation of gay love in the midst of a propaganda war is exactly the tone that Howson adopts, albeit in a parodic resurrection of the genre. This helps to explain the repressed sexuality of all these massive men, and by flavouring the imagery with the never-fading fascination with fascism, such paintings acquired a slew of celebrity buyers, including Steven Berkoff, David Bowie and Madonna, whose portraits form part of the show.

The absence of black people, and the very few women, is striking.

But amid the sound and fury, within this view of a human society composed of hostile and isolated beings, there are some great paintings that stand out as contemporary Scottish classics.

His depiction of ritual humiliation in an army barracks, Regimental Bath, 1985, although very reminiscent of Max Beckman, has a shock value all its own: it is a disturbing and important icon of a nightmare that reaches beyond the barracks into the discourse of casual homophobic abuse that exists in all walks of Scottish life, from the family to the school and the workplace.

His near monochrome Orange Parade, 1991, where a crippled, calculating leader is the still and chilling centre of a frenzied mob, is a uniquely compelling depiction of militant Protestantism.

And then, trailed by the BBC film crews that have feasted on his appetite for celebrity, Howson accompanied British soldiers to Bosnia in 1993. But there, in the ideological chaos of a genuine war, he was suddenly deprived of the capacity to satirise an easy target and the hard contour of his graphic style disintegrates completely.

This is real war, for once, and experienced without any comfortable cultural coordinates. The distress this causes to his identity as an artist is clear. He loses his political and moral compass and the paint becomes hazy and fragmented.

The best image from that period is the depiction of Bosnians trapped beyond our reach, a painting called Barrier Sunset, 1995. Between them and us is a borderline they cannot pass, but Howson still picks out a convincing portrait of their otherness as a family group, a kind of Bosniak normality that holds up under abnormal conditions.

A Howson used to hang in the old STUC headquarters in Glasgow, like a massive personification of the Scottish proletariat. It was gloomy, old-fashioned and everyone ignored it. But his paintings could equally adorn places at the other end of the political spectrum, among the far right.

The Sudden Blow, for example, is the depiction of an Aryan type who has just clocked you with a massive fist, and it belongs “in a private collection in Germany.”

This combination of extremes and ambivalence about their political significance is also to be found in his most recent work.

Is Barbarian, 2017, his portrait of Brexit, a celebration, or a warning, or both at the same time? The same can be said of his depiction of “Volk” ideology, Popolo Minuto, 2021, which is perhaps his best depiction of nationalist myth-making. He has simply swapped the swastika for the St George’s cross.

It is by making images that resonate at both extremes of the political arena that Howson’s work is uniquely pugnacious and alarming. And his significance in Scotland is to have shattered ideological taboos about representing such extremes, and to have brought them to the surface in a welter of heroic ugliness.

It is this, rather than illustration of Dante’s Divine Comedy or the much touted path towards Christian redemption, that is the consistent thread through the 40 years of Howson’s painting as represented in this massive retrospective.

It also feels like a significant cultural event, a kind of exorcism.

This is partly because he is so frank about numerous mental health issues to an unexpected degree, but mostly because the whole show feels like the paroxysm of a Calvinist world view. This is a thundering Manichaean nightmare rendered heroically vast in order, one hopes, to be grasped in all its awfulness, and to be done with once and for all.

Runs at City Art Centre, Edinburgh until October 1, info: edinburghmuseums.org.uk; also at Flowers Gallery, London until July 8, info: flowersgallery.com