This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

The Artists International Association

Tate Britain, London

UNLIKE most working-class children, when Cliff Rowe left school in 1918 aged 14 he went to the local art school rather than going straight to work. Aged 19 he was earning a living as a commercial artist, but painting in his own time. He accepted the profession’s competitive, individualist values, until someone loaned him the Communist Manifesto. Convinced of its logic he became one of Britain’s most principled, lifelong communist artists.

In 1930 he travelled to the young USSR, then a beacon of hope to his generation ravaged by the Hungry Twenties, and where there was plentiful illustration work. Inspired by Soviet cultural policies and the USA’s John Reed Clubs, Rowe initiated the founding of the Artist International (AI) in 1933.

This small Marxist group included Betty Rea, another returnee from the USSR, and the emigre sculptor Peter Laszlo Peri who brought valuable experience of his native Hungary’s 1919 Soviet and of political activism in the Weimar Republic. Although Rea later revoked her communism she remained an AI member and its dynamic secretary for several years.

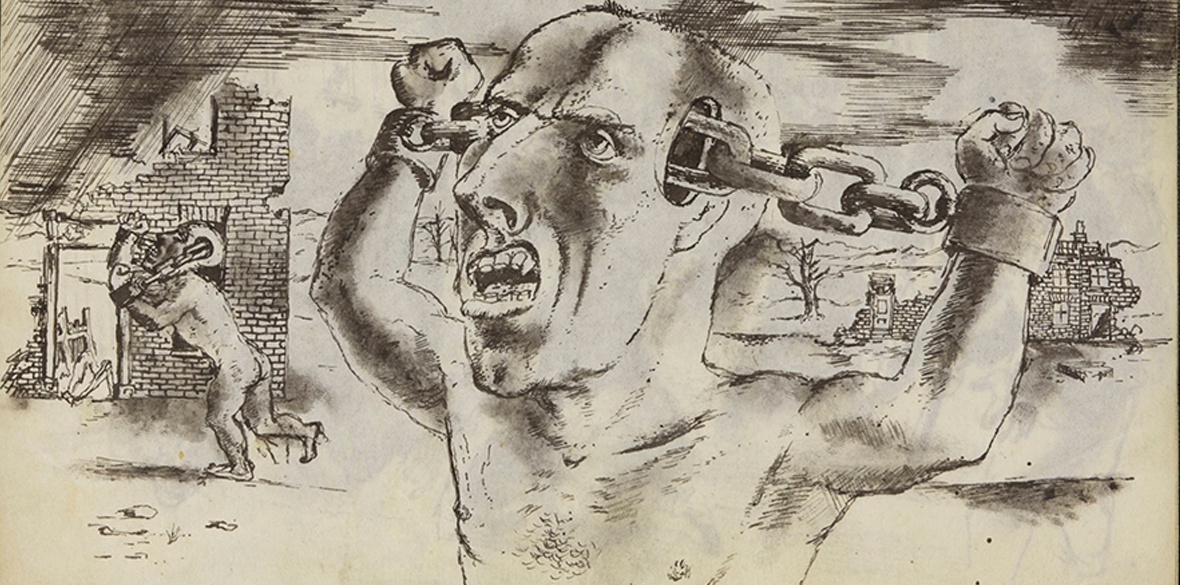

The AI was committed to the artist’s social responsibility and to art as weapon for social and/or political change. In 1935, inspired by France’s anti-fascist Popular Front, it moderated its Marxist aims to become the Artists International Association (AIA) under the new slogan “Unity of artists against fascism and war and the suppression of culture.” This widened membership which peaked during World War II and diminished during the Cold War.

The AIA was stylistically inclusive and members ranged from Modernist pioneers such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth to traditional realists such as Percy Horton. The younger generation included the realists Clive Branson and Patrick Carpenter (1920-1960) who represented these on the AIA committee. The association was committed to internationalism, anti-fascism and peace to combat the rising right-wing nationalism which threatened another European war. In the rather parochial British art world it was proud of its foreign members including the New Zealander James Boswell and the Hungarian Peter Peri.

During WWII many AIA artists joined the British army including Clive Branson who was killed in action aged 35. His realist painting Bombed Women and Search Lights of 1940 conveys war’s destruction and chaos but also the heroism of the two women who flee their homes carrying salvaged bedding.

Boswell’s and Carpenter’s wartime works satirised the class-based injustices of army life. Boswell depicted the officer class as savage, mindless bulls in army uniforms for the progressive magazine Our Time. Carpenter’s Army Red Tape revealed the idiocy of its bureaucracy.

Unlike the mostly middle-class official war artists, who were paid and dispensed from normal military duties, conscripted soldier artists like Carpenter could only paint while on leave. In his biography he wrote: “Born 1920. Working-class family. Father a postman. Born in Chelsea and lived there until 19 years old. Chelsea, known as one of the artists’ quarters on London, also had a large working-class slum area... in these streets [he] spent part of his early life.”

He won a scholarship to a secondary school where he first became class conscious because of the division between scholarship and fee-paying boys. In 1937 he joined the Communist Party and the AIA, and in 1938 became a student representative on its committee. That year he joined anti-fascist demonstrations and those supporting the Spanish Republic. He joined the army in 1940 and served in North Africa and Italy.

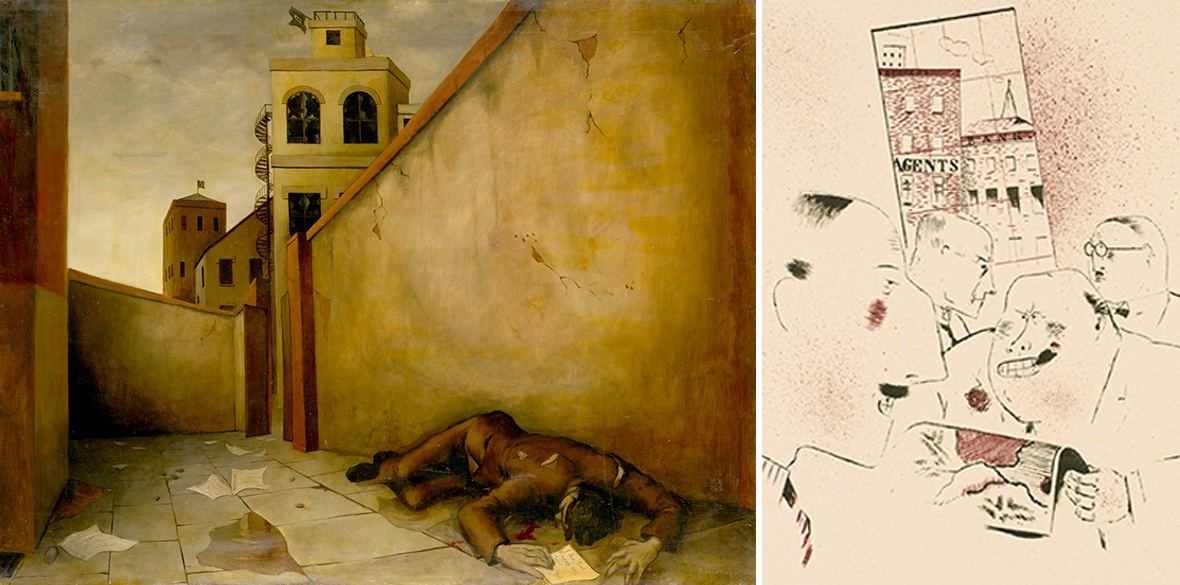

In 1943 Carpenter painted the Death of Gabriel Peri while on embarkation leave saying it was his “first really serious socialist realist painting.” Painted in a precise realist manner, its sharp diagonals create a strong spatial recession and it’s simplification of surfaces highlight the geometric shapes giving an emotive quality to its tragic subject that depicts the Nazis’ murder of the editor of L’Humanite (the French communist newspaper) during the Paris occupation.

In 1948 the AIA was riven by an anti-communist campaign initiated by Beryl Sinclair and Stephen Bone calling for the suspension of the AIA’s 1938 constitution’s clause 2f that committed it “to take part in any political activity” or “other actions in sympathy with it’s aims.” Carpenter, now on the AIA’s central committee, opposed this change, arguing that the Association should “do everything in its power to further the cause of peace [and] develop friendly contacts with artists and intellectuals in all countries.” Carpenter’s amendment won, but a vindictive Sinclair declared the votes invalid on administrative grounds.

The political debate bled into a crude Modernist versus Realist aesthetic opposition which linked the former to “freedom” and the latter to communist “propaganda”. In a letter to the New Statesman and Nation in April 1953 Carpenter argued that “all art is propaganda. The fundamental problem in this debate is whether it should be propaganda for man or against him.”

Yet given the Cold War demonisation of the Soviet Union and therefore also its socialist aesthetics, it is not surprising that the AIA soon lost its socio-political raison d’etre, and degenerated into an anodyne artists society with no clear vision.

I saw this important exhibition with great pleasure especially as few British Socialist Realist paintings exist and they are rarely exhibited. Yet I am surprised that the Tate’s publicity barely mentions it nor signposts it inside the gallery but tucks it away in the lone exhibition room near the cafeteria where many visitors may miss it.

Nor is there a catalogue or even an explanatory leaflet. This makes this “display” feel like a grudging token nod rather than a wholehearted acknowledgement of this hitherto neglected aspect of British art.

I salute its curators but feel that larger budgets should have covered a publication. This omission may be partly due to unconscious bias or conscious opposition by powerful people at the Tate to the political beliefs of these neglected artists who were communists or committed socialists.

For an institution that has long privileged formal innovation in art, the fact that the Tate only bought Carpenter’s 1943 painting in 2020, when he was long dead, does reflect a political bias against the organised left.

Runs until July 15 2025. Guest curator Andy Friend unpacks the history of Britain's Artists' International Tour: ARTISTS AGAINST FASCISM AND WAR, November 12, December 10, January 14, February 11 and March 11. For more information see: tate.org.uk https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-britain/display/art-around-the-building/artists-international-first-decade